Jane Austen - Reading Guide #3

Everything you need to do a deep dive in the excellent works of Ms Jane Austen: annotation system, companion reads, criticism, lectures, and more.

“The person, be it gentleman or lady, who has not pleasure in a good novel, must be intolerably stupid” - Northanger Abbey, Jane Austen

It is a truth universally acknowledged that reading Jane Austen’s novels refines both the senses and the sensibilities. I’ve been a regular reader of hers for more than ten years, and she never fails to amaze me. Every time I reread one of her books I discover something new, some new detail or hidden meaning found in a joke, gesture, glance, etc. She was a genius at understanding people and judging their characters; their oddities and neuroses; exploring different aspects of polite society through subtle acts of selfishness and kindness. I’m never bored reading Austen.

I’m one of the people who believes that a good novel can instil in you more wisdom about life than any non-fiction book can. I’ve laughed and cried and fallen in love many times while reading her works, and they have been worth companions in different periods of my life. Emma teaches you to laugh at yourself through her humbling experience; Elizabeth can make you fond of walking and beware first impressions; Anne can prove you that being hopeful is not naive; Fanny can show you that softness is also a strenght; Catherine is a hilarious example of maintaining your childlike wonder; Elinor demonstrates the power of resilience, and Marianne instructs you in the pangs of passion, even in a world of frigids.

2026 could be the year when you decide to read all of Jane Austen’s works (I’ve been wanting to do this for ages), and this guide may hold your hand while you pursue this project.

This is the third reading guide I wrote, and if you missed the other two, here they are:

Victorian Literature - Reading Guide #2

My reading life owes much to Victorian novels. Because of it, I got interested in classic literature and became what I would call ‘a real reader’. Until that moment (around 2020), I didn’t know anything about literature, classic or not. Victorian novels made me curious and excited to learn…

Shakespeare's Plays - Reading Guide #1

“Shakespeare was the strongest manifestation, the psychic message of a whole generation, expressing through the senses, a time turned passionately enthusiastic” — Stefan Zweig

I. Gentry & Daughters: a brief context

“I am not a romantic you know. I never was. I ask only a comfortable home” - Pride and Prejudice, Jane Austen

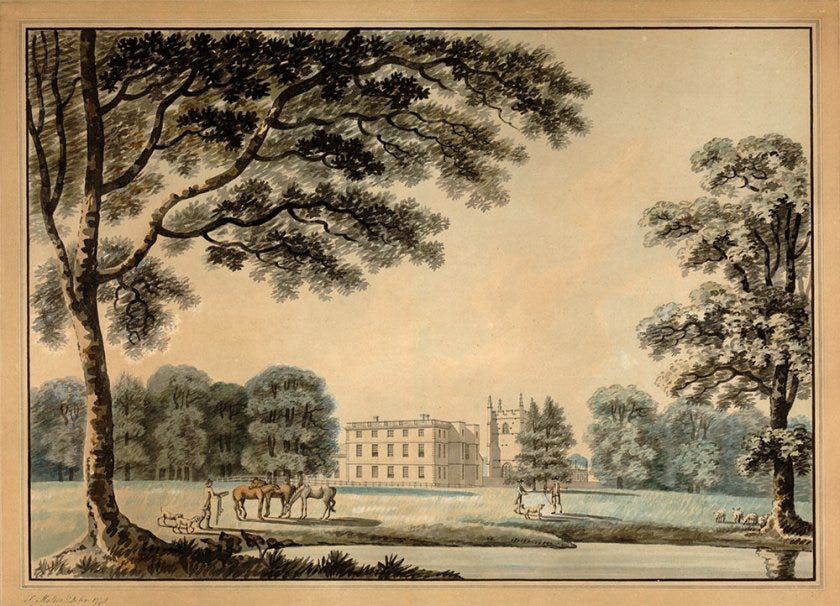

Jane Austen was born on December 16th, 1775, in Steventon, Hampshire, during a particularly harsh winter. She was the second youngest of eight children — a rather impressive offspring even by Georgian standards, especially for a middle-class family with limited means. Or, as historian Lucy Worsley puts it, a pseudo-gentry family: respectable people from the countryside, but not landed.

Jane’s father, the Reverend George Austen, was the rector of Steventon and a gentleman. Orphaned at nine, he went to live in London with an uncle who was a bookseller, later studied at Oxford, and eventually entered the clergy. His wife, Cassandra, kept busy managing both their many children and the family’s small farm (though they were able to employ servants). Despite having a few aristocratic connections in her extended family, she too belonged to the lower ranks of the gentry, making the marriage socially “suitable,” at least on paper. Whether their temperaments matched is another story (I cannot help but wonder if Jane’s description of Mr and Mrs Bennett's marriage in Pride and Prejudice was inspired by her parents).

To supplement his income, Mr Austen opened a boarding school for boys at his rectory, taking in about ten pupils and teaching them according to the standards of the day (after all, as an Oxford man, he had the right credentials, and was also reportedly intelligent, cultured, and quite handsome). As a result, Jane grew up surrounded by boys; not only her six brothers (she had just one sister), but a rotating crowd of students as well. One can easily picture the commotion of a household with sixteen boys under one roof, and imagine how such a scene might have influenced Jane’s psychological development. Anyone who has read Mansfield Park will remember the shocking description of Fanny’s house in Portsmouth, full of ill-mannered children. I suppose the inspiration may have come from experience.

Considering this context and the barbaric writings contained in Austen’s Juvenilia, Claire Tomalin in Jane Austen: A Life said that the young author “was a tough and unsentimental child, drawn to rude, anarchic imaginings and black jokes”. She may have found rich material for that sharp humour in the conversations of her father’s pupils and may even have joined in herself. “If she was at first shocked by what she heard,” Tomalin writes, “she was soon learning how to shock by writing it down”.

By all accounts, Jane was always an intelligent, astute person (with a rather scathing sense of humour even as an adult) and, contrary to popular belief, her life was not a linear and peaceful sequence of domestic events. She went through several changes of environment, attending a boarding school for girls, spending months at the homes of fairly distant relatives, and in 1800 she moved from bucolic Steventon to bustling Bath — certainly quite a transition. Her family’s permanent financial instability partly influenced these changes, and this is something that is conveyed in all her novels: her heroines (with the exception of Emma) always face the threat of destitution because, due to the law and social conditions of England at the time, a woman’s financial status depended entirely on her male relatives including, of course, her husband.

This is why Mrs. Bennet in Pride and Prejudice appears so desperate to the point of absurdity to modern readers, but rather unfairly so. Imagine being responsible for the financial future of five daughters (and no sons) who cannot legally inherit a penny because they are women. Under those circumstances, of course she’s determined to secure the dashing Mr Bingley for her eldest. If we put the economic conditions of the 18th and 19th centuries into account, Mrs Bennet’s poor nerves begin to look a little less comic and a little more understandable.

Despite the gender inequality, the fall of the country life, the rise of industrialisation, the expansion of colonialism and the Napoleonic Wars, the eighteenth century was also a time of intellectual revolution. The emergence of the novel as we know it during this period coincided with a renewed interest in the human faculties, propelled by the illuminists. This new literary form, as explained by Ian Watt in The Rise of the Novel, provoked lots of controversies over the relationship between truth and fiction, art and nature, entertainment and instruction. Jane vigorously entered these discussions, since in every one of her books we find commentary on the habit of reading, including explicit defences of the novel, as seen in Northanger Abbey.

By the time Jane was twenty-five, she had already drafted the novels that would become Sense and Sensibility, Pride and Prejudice, and Northanger Abbey; she wrote those early works rather slowly since she didn’t have the appropriate time or space to dedicate herself to writing as a man could. As Virginia Woolf explained better than anyone else: she didn’t have a room of her own. Finally, in 1811, Sense and Sensibility became her first published novel, and she began working on Mansfield Park. In 1813, Pride and Prejudice was published to great acclaim, followed by Mansfield Park in 1814 and Emma in 1815. Sadly, she died in 1817 at just forty-one, right after completing Persuasion, which was published in 1818 alongside Northanger Abbey. She left an unfinished novel titled Sanditon, which is easily available to read today, among her other short works and fragments.

As the daughter of the pseudo gentry, Jane couldn’t publish her work under her own name, as it would be considered socially inappropriate. Usually, women who did that were either aristocratic (like the pioneer Margaret Cavendish) or had a good financial reason to do it. So, she used pseudonyms to correspond with her publishers; other times, her father or brother negotiated on her behalf. It was only later in life, when she was probably more confident and her work well established, that she would go and do the dealing herself. Even then, she never published under her real name during her lifetime; her books appeared simply as works “by a Lady.”

II. Where to Begin: build your reading path

“A fondness for reading, properly directed, must be an education in itself”- Mansfield Park, Jane Austen

If you happen to be among that small and curious portion of the reading public who have never opened a novel by Miss Austen (or who, having done so once in some distant schoolroom, dismissed her as stuffy), and now find yourself uncertain where to begin, I propose a reading project that can be adapted to your reading pace.

First of all, if you’d like to know my subjective opinion on which of the author’s books are my favourites, they are (in that order): Pride & Prejudice, Emma, and Persuasion. But I am not being indulgent when I say that all Austen novels have something to be appreciated.

Before we continue, I think it is pertinent that I tell you a little about each novel and my experience reading them.

A Synopsis of sorts:

Sense & Sensibility: this book went through lots of changes; it was going to be an epistolary novel, composed of letters between the two main characters, sisters Elinor and Marianne. The girls are very different. As you might guess from the title, one represents “common sense” with her rational, reserved, and introverted temperament; the other represents “passion,” being a dramatic, romantically incorrigible, and naive young woman. The two will have to deal with the loss of economic stability after their father’s death, as well as new loves, whether reciprocated or not. It is one of Austen’s books that I like the least, mainly because I can’t stand Marianne. However, I know several people who love the book (and her), and I promise I understand perfectly why.

Pride & Prejudice: you surely know something about this novel, at least about the infamous Mr. Darcy. There are plausible reasons for P&P to have all this hype: it brings together all of Austen’s best qualities and the story just gets better and better without a single moment of boredom, culminating in a perfect (almost fairy-tale) ending. This book is a great mystery of character: who is Mr. Darcy really? And Mr. Whickham? And what about Bingley? Does Elizabeth know herself as well as she thinks she does? In the end, we piece together the puzzle through letters and various testimonials, and from this puzzle we can finally discover the interpersonal mystery that governs one of the most well-crafted novels in Western literature.

Masnfield Park: Austen’s most serious book, in my opinion. It will certainly be more appreciated by introverts, who can understand Fanny’s shyness and introspection better than I can. There is a significant change in the writing and reflective tone of this book, composed between 1811 and 1813 and published in 1814, when Austen was 39 (an important difference since the last two were written in her early 20s). The paragraphs written in the narrator’s voice are much longer and more comprehensive in terms of the novel’s themes (namely, duty, belonging, family, and moral responsibility); and the protagonist’s love story is not as exciting as in other books — it is more about her personal journey. Since I find Fanny to be a boring moralist, this is my least favorite Austen book.

Emma: Austen famously said that Emma was a character only she would like. Little did she know how wrong she was, because I love Emma. I think she is fantastic despite her arrogance and stubbornness. This is Austen’s longest book, and perhaps the most sophisticated in its irony. Unlike all the other heroines, Emma does not have to face the threat of economic destitution, and therefore does not need to marry for money. In fact, she begins the book believing that she will never marry because she is aware that nowhere else will she be as much mistress of herself and her home as she is living with her father, a wealthy country squire and perhaps my favorite character in the entire Austen universe. Emma, therefore, will need to face an internal challenge: that of overcoming her own misconceptions and admitting her own faults. It is a problem that many can relate to.

Persuasion: Completely different from the previous one, Persuasion is Austen’s most subtle and melancholic novel. Having been written shortly before the author’s death, it is possible to sense a certain wistfulness concerning “lost time” and roads not taken; it is a story determined by a choice made in the past. Anne Elliot is 28 years old and, therefore, practically an old spinster by the standards of the time. Almost a decade earlier, she gave up marrying the man she loved because he could not afford to support her. When she had already resigned herself to being single, she unexpectedly meets him again, and thus a new chance arises for this couple. It is a very beautiful book because it deals delicately with second chances, showing without cheesiness or naivety that it is never too late for happiness. Anne really inspires me to be hopeful, and I appreciate that.

Northanger Abbey: Written at the same time as S&S and P&P but only published posthumously, Northanger Abbey is the funniest book on this list. I genuinely laughed out loud while reading it, mainly because of its strong parodic aspect: Austen wrote this book as a satire of the Gothic novels that were fashionable at the time. Although the protagonist Catherine is a bit dull, I still like her very much because this is intentional: unlike Gothic protagonists, who have something essentially unique and special about them, Austen insists from the beginning that Catherine is just an ordinary girl, neither worse nor better. Her most distinctive feature is her passion for books, particularly...Gothic novels. The more scandalous, the better. Catherine’s great challenge is to mature and understand that life is not like in novels (today we would say movies). Be patient with poor Catherine’s foolishness!

I have written about Austen before, so if you’re interested, here are the essays (the Mansfield one is a favourite of mine):

The Ethics of Space in Mansfield Park

Thus the house is not experienced from day to day only, on the thread of a narrative, or in the telling of our own story. Through dreams, the various dwelling places in our lives co-penetrate and retain the treasures of former days. – Gaston Bachelard

In Praise of Walking: or, a Lesson from Elizabeth Bennet

This year I started a new job relatively close to my house. It's a 1.7 km walk. In the first month, I ordered my uber every day to and fro but, eventually, I realised it was a financially stupid decision. Besides, the traffic is horrendous, the drivers are rarely polite and their cars are falling to pieces – overall a stressful experience which wasn’t w…

A Year Reading Jane Austen

Now let’s get down to the project. Considering that we have six complete novels, a book of “short stories” (which are more like unfinished novels or novellas: The Watsons, Lady Susan and Sanditon), and a collection of her “juvenilia” (that is, her early writings), we have eight works to read, and my suggestion is that you read four in the first semester and four in the second. Could be something like this:

January-February …….. Pride & Prejudice

March ……… Persuasion

April ……… Short Works

May-June ……… Sense & Sensibility

July ……… Juvenilia

August-September ……… Mansfield Park

October ……… Northanger Abbey (spooky month!)

November-December ……… Emma

There are different reading orders, depending on your interest and intention. Your reading order can be:

Chronological (when she wrote them):

Juvenilia, Lady Susan, Sense and Sensibility, Pride and Prejudice, Northanger Abbey, The Watsons, Mansfield Park, Emma, Persuasion, Saditon

Publication:

Juvenilia, Sense and Sensibility, Pride and Prejudice, Mansfield Park, Emma, Persuasion, Northanger Abbey, Lady Susan, The Watsons, Sanditon

My Personal Recommendation:

Pride and Prejudice, Persuasion, Northanger Abbey, Sense and Sensibility, Mansfield Park, Emma, Juvenilia, (short works)

Considering the descriptions of the books I gave, here’s my personal recommendation list, the one I’d give to a friend. You can’t go wrong with P&P. As I said, it encompasses all the best aspects of Austen as a writer. Persuasion and Northanger Abbey are her shorter works, one displaying all of Austen’s elegance, the other all of her humour. Once you’re acquainted (and hopefully in love) with her work, you’re ready to take in her most moralistic and slow books, namely S&S and Mansfield Park. After you went through all this, you’re ready to appreciate all of the ironic complexities and length of the magnificent Emma. Then, after reading all of her novels, you can check her minor works to get even more acquainted with her development as an artist.

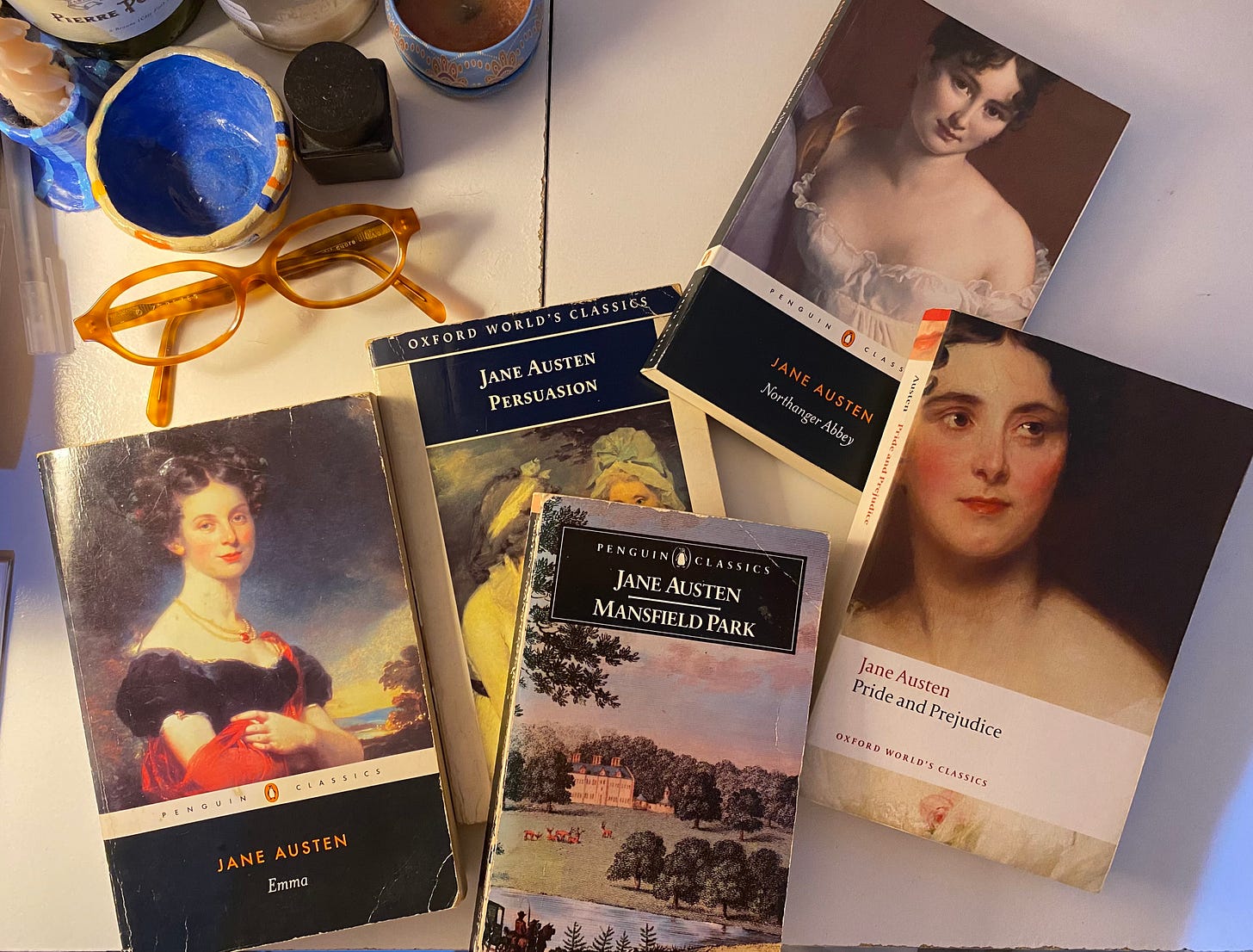

My Favourite Editions:

As I always say here, I’m very particular about which publisher I buy my books from. Since I almost exclusively purchase used books, I tend to look for the good old Penguins and Oxfords. I value a good introduction and explanatory notes.

III. Reading Properly: annotate your books

“It is this delightful habit of journalizing which largely contributes to form the easy style of writing for which ladies are so generally celebrated” - Northanger Abbey, Jane Austen

It’s simply impossible for me to read without a pen in hand. I can’t properly engage with a text without literally responding to it through comments in the margins, underlining and journaling. So I definitely encourage you to not be pristine — write all over your books, make it yours, and when you reread, you can even disagree with yourself (I always laugh at my old comments).

This method is not only fun but it helps you to retain better what you read, to develop critical thinking, to remember scenes and quotes once the book is closed, etc.. When you’re in conversation with the author, you are on the right path to understanding. This is active reading, which I always encourage my readers to do.

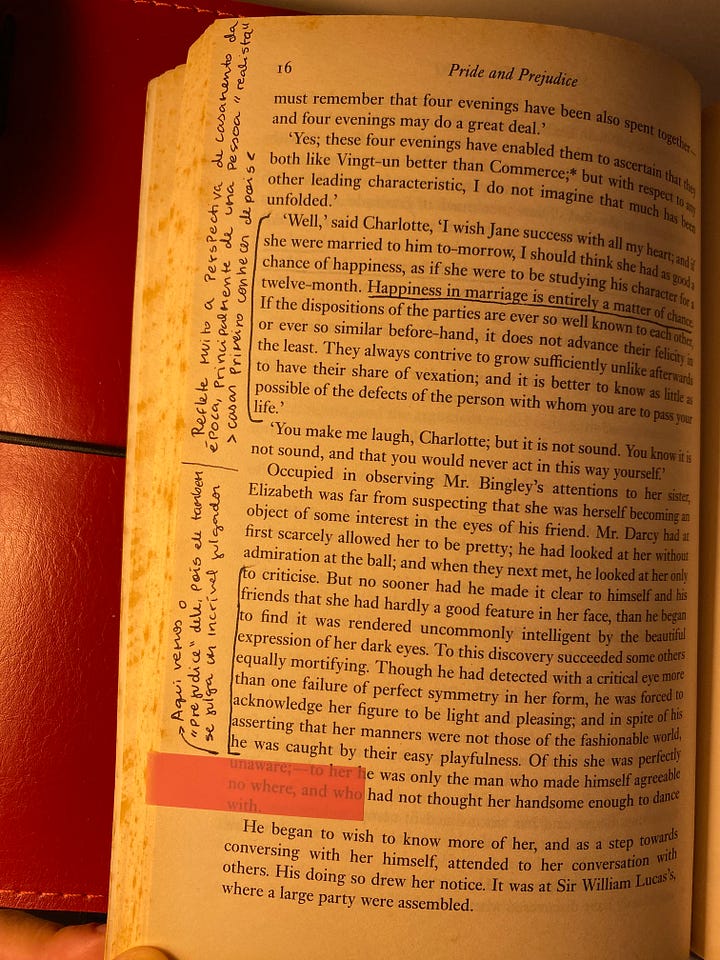

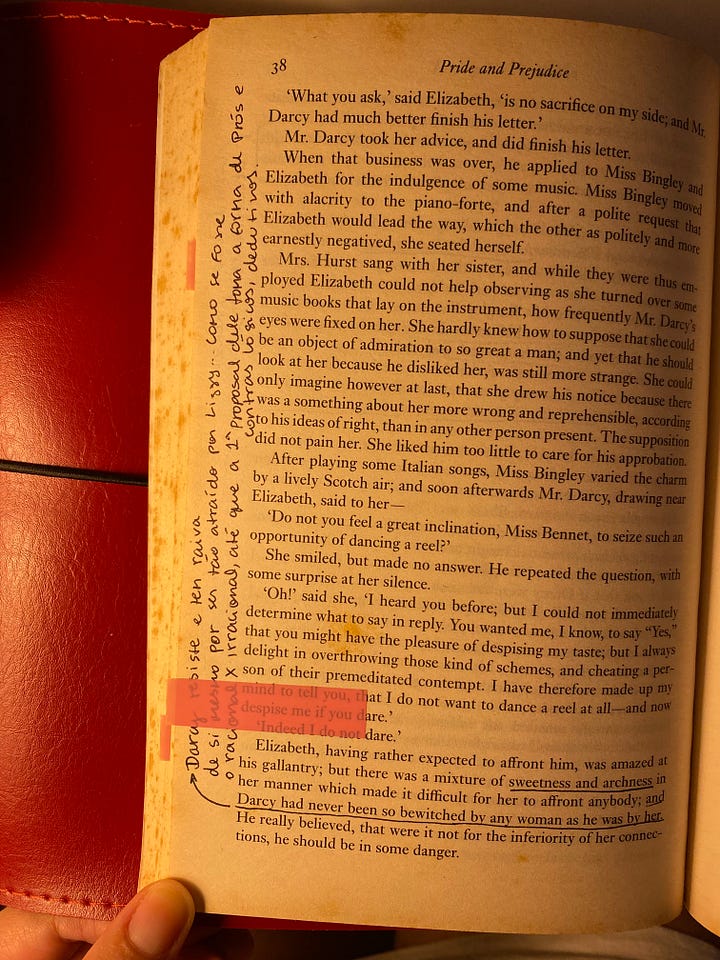

In the image above, you can see my well-read copy of Pride and Prejudice. Your annotations don’t have to be extremely academic or incredibly insightful. They are for your comprehension only; what matters is that you’re not passively absorbing information. In this novel particularly, I focused on the psychological development of Darcy and Elizabeth, and highlighted sections where the “mystery of character” was most evident. Naturally, I also underlined the romantic scenes that made me swoon.

Here’s how my note-taking system works:

Establish your interests: When I don’t already know what I want to focus on in a novel, I begin by looking up its central themes or characters online and selecting whatever piques my interest. I don’t worry much about spoilers because, honestly, an Austen novel cannot be ruined by spoilers, since they’re not built on suspense (at least not in the traditional sense), but on character.

Colour-coded tabs: I use colored tabs, assigning a different colour to each theme. On the back page, I write down the colour key so I don’t forget it later. For Pride and Prejudice, for instance, I was mainly interested in “moral and psychological questions” (dark pink) and “character mystery” (light pink). It’s a system that would probably make sense only to me, which is entirely the point.

Be willing to pay attention: This method encourages attentive reading, since it requires me to recognise themes as they appear and mark them as I go. I also like to write in the margins brief thoughts, associations, or questions that I can later develop in my reading journal.

Critical Journaling: I keep my reading journal in two distinct ways, depending on the complexity of the book and the depth of analysis I’m after. Mansfield Park, for example, raises interesting questions about the relationship between physical space and moral character and how they mutually determine each other. When I wrote the essay on it, I paid particular attention to scenes where this theme surfaced, so that I could later examine them more critically in the journal.

Impressionistic Journaling: If I’m reading purely for pleasure, the journal becomes a space for recording impressions and reflections. It’s where I register my memories about the book, and where I have a conversation with myself about it. It’s also practical: since I write about my reading on my blog, these notes often turn out to be the basis of my reviews.

In short, my reading journal is written in collaboration with my own highlights and annotations made in the physical copy. If I don’t annotate in the book, there’s nothing to write in the reading journal.

Don’t forget to use the endnotes in your edition to complement your annotations!

IV. Companion Pieces: a Jane Austen syllabus

“Emma has been meaning to read more ever since she was twelve years old. […] But I have done with expecting any course of steady reading from Emma. She will never submit to any thing requiring industry and patience” - Emma, Jane Austen

Biographical works:

My Aunt Jane: A Memoir - Caroline Austen

Jane Austen: Facts and Problems - R.W. Chapman

Jane Austen at Home: A Biography - Lucy Worsley

Jane Austen: A Life - Claire Tomalin (I’m currently reading this one and it’s good)

Jane Austen: A Literary Life - Jan Fergus

Jane Austen in Context:

Jane Austen: A Critical Bibliography - R.W. Chapman

Women Writing About Money: Women’s Fiction in England, 1790-1820 - Edward Copeland

Small Change: Women, Learning, Patriotism, 1750-1810 - Harriet Guest

English Fiction of the Romantic Period, 1789-1830 - Gary Kelly

Women’s Reading in Britain 1750-1835: A Dangerous Recreation - Jacqueline Pearson

The Gentleman’s Daughter: Women’s Lives in Georgian England - Amanda Vickery

The Rise of the Novel - Ian Watt

Critical Works:

Jane Austen’s Novels: Social Change and Literary Form - Julia Prewitt Brown

Jane Austen and the War of Ideas - Marilyn Butler

The Cambridge Companion to Jane Austen

The Improvement of the Estate: A Study of Jane Austen’s Novels - Alistair Duckworth

Inside the House of Fiction: Jane Austen’s Tenants of Possibility - Susan Gubar and Sandra Gilbert

Jane Austen: Women, Politics, and the Novel - Claudia Johnson

The Proper Lady and the Woman Writer: Ideology as Style in the Works of Mary Wollstonecraft, Mary Shelley, Jane Austen - Mary Poovey

How to Study a Jane Austen Novel - Vivien Jones

Jane Austen: Feminism and Fiction - Margaret Kirkham

Jane Austen - Tony Tanner

Romantic Austen: Sexual Politics and the Literary Canon - Clara Tuite

Communities of Women - Nina Auerbach

A Reading of Jane Austen - Barbara Hardy

Northanger Abbey and Persuasion: A Casebook - B.C. Southam

Jane Austen: A Collection of Critical Essays - Ian Watt

Jane Austen and Leisure - David Selwyn

Recommended Articles and Essays:

Nabokov, Vladimir. ‘Mansfield Park’. Lectures on Literature. 1980;

Benis, Toby R. “The Austen Effect: Remaking Romantic History as a Novel of Manners.” The Wordsworth Circle 42, no. 3 (2011): 183–86.

Lau, Beth. “Jane Austen and John Keats: Negative Capability, Romance and Reality.” Keats-Shelley Journal 55 (2006): 81–110.

Rosmarin, Adena. “‘Misreading’ Emma: The Powers and Perfidies of Interpretive History.” ELH 51, no. 2 (1984): 315–42.

Banfield, Ann. ‘The Moral Landscape of Mansfield Park.’ Nineteenth-Century Fiction 26, no. 1, 1971;

Rooney, Sally. Misreading Ulysses*. Paris Review, 2022; (in this great essay, Rooney explains how we wouldn’t have most of modern literature, including Ulysses, without Jane Austen)

Auerbach, Nina. ‘Jane Austen’s Dangerous Charm: Feeling as One Ought about Fanny Price.’ Jane Austen: New Perspectives. 1983;

Copeland, Edward. “Fictions of Employment: Jane Austen and the Woman’s Novel.” Studies in Philology 85, no. 1 (1988): 114–24.

Fricke, Christel. “The Challenges of Pride and Prejudice: Adam Smith and Jane Austen on Moral Education.” Revue Internationale de Philosophie 68, n° 269 (3) (2014): 343–72.

Cohen, Rachel. Living Through Turbulent Times with Jane Austen. The New Yorker, 2020.

HIRSCH, GORDON. “Shame, Pride and Prejudice: Jane Austen’s Psychological Sophistication.” Mosaic: A Journal for the Interdisciplinary Study of Literature 25, no. 1 (1992): 63–78.

Kestner, Joseph. “Jane Austen: The Tradition of the English Romantic Novel, 1800–1832.” The Wordsworth Circle 7, no. 4 (1976): 297–311.

POLLACK-PELZNER, DANIEL. “Jane Austen, the Prose Shakespeare.” Studies in English Literature, 1500-1900 53, no. 4 (2013): 763–92.

Jane Austen’s Library:

The Vicar of Wakefield - Oliver Goldsmith (1766)

The Progress of Romance - Clara Reeve (1785)

Camilla - Frances Burney (1796)

Sir Charles Grandison - Samuel Richardson (1753)

Belinda - Maria Edgeworth (1801)

Essay on the Picturesque - Uvedale Price (1794)

The Rambler, Nos. 4 and 97 - Samuel Johnson (1750-1752)

Mysteries of Udolpho - Ann Radcliffe (1794)

The Romance of the Forest - Ann Radcliffe (1791)

The Children of the Abbey - Regina Maria Roche (1798)

The Female Quixote - Charlotte Lennox

The Complete Plays of William Shakespeare (many plays are constantly mentioned and subtly referenced throughout the novels, for instance, Mansfield Park has an important scene involving Shakespeare’s Henry VIII)

Tom Jones - Henry Fielding (1749)

The Task - William Cowper (1785)

Online Resources:

Jane Austen Books website - they’re an online store, I don’t buy anything there, but it’s good for finding out books on Austen!

Internet Archive (you can find many books listed there)

JSTOR (THE place to find academic articles)

Gale Primary Sources website - a place to find primary research sources, offering access to digitised eighteenth and nineteenth-century collections

Duquense University library - provides an extensive list of Austen-related works

Video Lectures and Podcasts:

Hardcore Literature YouTube Channel — I’ve been following Ben for a long time, and he’s absolutely trustworthy book-wise. He makes these extremely long videos on how to read a specific book, and I believe he has other videos on Persuasion and Pride & Prejudice.

Jane Austen vs. Emily Brontë debate — first of all, I don’t think these two writers have anything in common except being women who published beloved books in the 19th century. However, the debate in itself is quite good, and I loved hearing the actors perform such great lines; it’s interesting to hear well-crafted sentences.

English Landscape: The Picturesque (Gresham Lectures) — Gresham’s YouTube channel has many wonderful lectures available, and I’ve been a fan of them for years. This video offers an important aesthetic context to Austen’s work, since the concept of the Picturesque was all the rage during her time, and it’s frequently mentioned in her novels.

Lucy Worsley’s Jane Austen: Behind Closed Doors Documentary — Lucy is one of the current pop historians, and of course we couldn’t leave her BBC docs out of this list. This documentary offers a glimpse of Jane’s life during the Georgian period, including the economic struggles she suffered — something we encounter in many of her novels.

Jane Austen: Patriotism and Prejudice (Gresham Lectures) — Naturally, Austen’s novels aren’t just love stories and family dramas; we must also consider their political implications critically, and this lecture can offer good insights in this respect.

Jane Austen, Persuasion: Irony and the Mysterious Vagaries of Narrative (Gresham Lectures) — One of the most fascinating aspects of Austen’s novels is the narrative style. She is well known for her particular writing format that we now call “free indirect discourse”, and in this lecture, the wonderful Prof. Belinda Jack offers an exploration of her witty and mischievous prose.

Classical Stuff You Should Know Podcast: Pride and Prejudice & Sense & Sensibility — this is one of my favourite podcasts, composed by three hilarious high school professors. They discuss the plot and aspects of the novel with humour and clarity.

You’re Dead to Me Podcast: Jane Austen, the life of a Regency literary icon — another favourite podcast, where a historian (or another kind of specialist) and a comedian get together to discuss a historical character. It’s perfect for the history buffs who enjoy a bit of banter.

History Extra Podcast: Jane Austen and Tudor London — this one is more serious than the others, and you feel like you’re in a proper university class listening to it. Austen and the Tudors sound like an unexpected connection, so if you’re curious like me, give it a listen!

Jane Austen Stories Narrated by Julie Andrews: Pride and Prejudice — imagine my total bliss when I discovered this new series of Austen’s audiobooks narrated by my dearest Julie Andrews (I love her as if she were my grandma). I’m already planning a P&P reread with this audiobook.

Close Reads Podcast: Persuasion — I really appreciate the work done by the folks at

, and I reread Persuasion this year, accompanied by their podcast. I suggest you do the same!

This is absolutely brilliant!!

I shall send it to all of my friends who want to ‘get into’ reading Austen. There was also a lot for people already familiar with her work!

This is simply amazing. Even though I have read all her books (although would love to start looking at her juvenalia) I’m of a mind to re-read using this very powerful guide. Much appreciated 💕