Victorian Literature - Reading Guide #2

How to start reading Victorian Literature: novels, poetry, annotation systems, critical reading syllabus, research material, etc.

My reading life owes much to Victorian novels. Because of it, I got interested in classic literature and became what I would call ‘a real reader’. Until that moment (around 2020), I didn’t know anything about literature, classic or not. Victorian novels made me curious and excited to learn — so much so that I started studying literature independently, and I’ve been doing it for five years now.

Beginning with Oscar Wilde and Emily Brontë, I moved on to the other Brontës, George Eliot (also known as Mary Ann Evans), Hardy, Tennyson, and Trollope. For a long time, half of what I read in a year was Victorian Literature. Nowadays I read way more diversely, even though the Victorians still hold a place in my heart.

Therefore, after guiding you through Shakespeare, the second instalment had to be about the most fascinating and insufferable English period in history. And in case you missed the first guide:

Shakespeare's Plays - Reading Guide #1

“Shakespeare was the strongest manifestation, the psychic message of a whole generation, expressing through the senses, a time turned passionately enthusiastic” — Stefan Zweig

I. Who were the Victorians?

Queen Victoria’s coronation in 1837 marks the beginning of a new era in literature, just as her death in 1901 marked the end of a most idiosyncratic century with its heavy and intricate novels. According to Deidre David in The Cambridge Companion to Victorian Literature:

In general, the Victorian novel is notably ambitious. Eager to show it knows everything and everyone from probate law to dolls' dressmaking, from cosmopolitan financier to working-class river dredger, its pervasive omniscience has led J. Hillis Miller to speculate that a Victorian reading public dislodged from religious certainty by scientific discovery, found consolation in a novelistic power that both resembled divine omniscience and accepted responsibility for creation.

Indeed, when I think about Victorian novels, the first quality that comes to mind is ‘all-encompassing’. Victorian authors demand a lot from the reader — be it with George Eliot’s intellectual density or Charles Dickens’ multilayered plot — yet they deliver a lot in return. The three-volume format established the Victorian novel as anything but economic, so authors had to be creative to keep the reader engaged for over five hundred pages. They don’t always succeed: if I were Dickens’ editor, I would always cut at least a quarter of his narratives; the same goes for Wilkie Collins and Eliot in certain novels. The Brontë sisters, on the other hand, usually made good use of their pages. David attempts to clarify this attribute:

This is probably because [the novel] is about so many things: provincial politics, ecclesiastical infighting, city squalor, repressed sexuality, making money, losing money, imperial adventure, angels in the house, frightening New Women, scientific challenges to established religious beliefs, the value and function of the aesthetic life in a materialistic society (to name a few).

19th-century England probably saw more changes in one century than it did in the last 300 years. The country’s population grew from 8.9 to 32.5 million, which led to a huge migration from rural to industrial areas. People went from being farmers to factory workers: women and children were working 16 hours a day and earned a ridiculous sum, with no protection from the law, as we see in David Copperfield. Then the railroads invaded the fields, as described in Middlemarch. ‘The working class began to lobby for unionisation and universal male suffrage, most notably in the latter case through membership in the Chartist movement. Chartism, combined with serious economic depressions in the 1830s and 1840s and middle-class fears that continental revolution might cross the Channel, led to national debate about what Thomas Carlyle termed "The Condition-of-England" question’, David explains. There were the revolutionary Reform Bills of 1832 and 1867 on suffrage; Darwin’s ground-breaking The Origin of Species; the Great Exhibition of 1851; the Matrimonial Causes Act of 1857 that changed divorce laws. Later, the Empire began to collapse. And Oscar Wilde went to trial.

The Victorian Novel was the biggest mirror and judge of all these cultural changes.

II. Reading List

In anything fit to be called by the name of reading, the process itself should be absorbing and voluptuous; we should gloat over a book, be rapt clean out of ourselves, and rise from the perusal, our mind filled with the busiest, kaleidoscopic dance of images, incapable of sleep or of continuous thought. — Robert L. Stevenson

There are hundreds of Victorian novels out there. I don't claim to include all of them here, and I know you know that, but it's worth clarifying. After all, Anthony Trollope wrote forty-seven novels; Mary Elizabeth Braddon wrote over eighty; Margaret Oliphant, now rather ignored but hugely successful in her time, wrote nearly a hundred. The books included here are the most famous and important to the Victorian literary tradition, along with lesser-known works which I think are underrated. For example, George Eliot's Adam Bede is one of my favourite Victorian novels, and whenever I mention it, few people have read it or are even familiar with it.

Further, you will find lists of books based on subgenres and themes. Some subgenres, such as the Bildungsroman (or coming-of-age novel), are not listed here as a separate category because there are dozens of books that fit this format while addressing varied themes that may be more relevant to highlight. The Bildungsroman is nothing more than a narrative format in which the reader follows the development of a main character, from childhood and youth to a transformation or maturing of the individual. For example, David Copperfield, which is a classic coming-of-age novel, is listed alongside books that deal with the conditions of the working class in England because David's challenges in this context overlap, for me, with the fact that the book is based on his life’s trajectory.

All this to say that the choices I made are subjective, in the sense that they do not exclude other possibilities of categorisation, but they were made following a thematic logic aimed at helping you find new reading material.

Major Works

Making a list of this kind is always difficult and debatable, as I mentioned. However, for the purposes of this post and considering you trust my judgment, I listed 16 books from different genres that marked the Victorian Era in some important way, based on my knowledge and on many universities’ syllabi. I can't say that all of them are good, just that they have stood the test of time and still exert a significant influence on the literary tradition we have today.

Obs: I know some scholars don’t consider Henry James a Victorian novelist due to his unfortunate American birth. However, during his lifetime, he went to great lengths to convince everyone that he was as English as the Queen herself — so I will do him this favour because I like him, and will include him on our reading lists.

Vanity Fair - William Thackeray

Middlemarch - George Eliot

Great Expectations - Charles Dickens

The Woman in White - Wilkie Collins

Dracula - Bram Stoker

Oliver Twist - Charles Dickens

North and South - Elizabeth Gaskell

The Portrait of a Lady - Henry James

The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde - Robert Louis Stevenson

The Way We Live Now - Anthony Trollope

Lady Audley’s Secret - Mary Elizabeth Braddon

Jude the Obscure - Thomas Hardy

The Picture of Dorian Gray - Oscar Wilde

Jane Eyre - Charlotte Brontë

Wuthering Heights - Emily Brontë

The Tenant of Wildfell Hall - Anne Brontë

If you want to see more, check my “Victorian Essentials” list on Goodreads

My Favourite Works

Usually, a book becomes a favourite for sentimental reasons, rather than for admiration of its technique and/or intellectual contribution. An exception is the books by Wilde and Pater, which are the most special on this list because they changed the way I think about art and life, about myself as an artist, about how to pursue knowledge and beauty in the world, among other things of the sort.

The other novels moved me deeply through a mixture of beautiful writing and incredibly compelling characters whose stories made me forget I was reading fiction. Hetty's tragic fate in Adam Bede, Heathcliff's enforced misery in Wuthering Heights, Lucy's moral strength in Villette and Eustacia's incredibly relatable passion in The Return of the Native — all of which affected me in such a way that I never stopped thinking about those stories.

Adam Bede - George Eliot

Wuthering Heights - Emily Brontë

Villette - Charlotte Brontë

The Return of the Native - Thomas Hardy

The Picture of Dorian Gray - Oscar Wilde

Studies in the History of the Renaissance - Walter Pater

Poetry

The Victorian era brought many innovations, including a change in literary culture regarding textual form. While the 18th century was marked by poetry — both Augustan, with Alexander Pope, and Romantic, with Keats, Wordsworth, Coleridge etc. — the 19th century was the golden age of the novel. As such, Victorian poetry developed in the shadow of the all-encompassing Victorian novels and had a lesser influence on culture. Even so, the poetry should not be ignored. Notably, Tennyson's Arthurian poems are marvellously dramatic and entertaining.

Idylls of the King - Lord Alfred Tennyson

Goblin Market - Christina Rossetti

My Last Duchess and Other Poems - Robert Browning

Aurora Leigh - Elizabeth Barrett Browning

Selected Poems - William Morris

The House of Life - Dante Gabriel Rossetti

Spicelegium Poeticum, A Gathering of Verses - Gerard Manley Hopkins

Poems and Ballads - Algernon Charles Swinburne

A Child's Garden of Verses - Robert Louis Stevenson

A Shropshire Lad - A. E. Housman

Wessex Poems - Thomas Hardy

The Collected Poems - Emily Brontë

A Specific Selection: exploring the subgenres

There are various subgenres of Victorian fiction which I’ll be listing below, as well as a few categories of my own making, so you can have a general idea of the essence of many Victorian novels. This way, you can find something new that may interest you.

Newgate

Novels whose main theme is crime, inspired by the Newgate Calendar (because of Newgate Prison in London), which published the biographies of various criminals, were all the rage between the 1830s and 1840s and rapidly declined due to severe criticisms. The books are usually moralistic, dramatic, Manichean and politically punitive, especially in today's standards. If you don't mind that so much and you like unrealistic thrillers, adventure tales featuring criminals, and mystery stories set in London's slums, check out the following books:

Oliver Twist - Charles Dickens

Paul Clifford - Edward Bulwer-Lytton

Jack Sheppard - William Harrison Ainsworth

Catherine - William Thackeray

Sensation Novel

The Newgate novel did not survive the controversies and sort of evolved into the ‘Sensation Novel’, which also absorbed characteristics of melodrama. These novels deal with a mystery, usually involving a crime or scandal, but are centred around psychological and/or allegorical elements, illustrating the anxieties of the time about foreigners, adultery, sexuality and identity. In contrast to Newgate, the Sensation Novel places ordinary, respectable people in abnormal and amoral situations: the controversy was not distant anymore — the writers brought it inside respectable English households. If you like YA romances and have never read a classic before, you may like to start here; also, if you like plot-heavy dramas, reality shows, soap operas, or follow deuxmoi, you'll love them:

The Woman in White - Wilkie Collins

Desperate Remedies - Thomas Hardy

Lady Audley’s Secret - Mary-Elizabeth Braddon

Lady Anna - Anthony Trollope

Trilby - George du Maurier

East Lynne - Ellen Wood

Uncle Silas - Sheridan Le Fanu

Armadale - Wilkie Collins

Griffith Gaunt - Charles Reade

Aurora Floyd - Mary Elizabeth Braddon

The Moonstone - Wilkie Collins

The Sad Heroine: Governess, Widow, Fallen Woman…

As you may know, women suffered a lot back then. We still do, but it’s important to recognise how far we have come. Imagine having absolutely no rights, and your only way to survive is to make a good marriage. Your life is defined first by your father, then by your husband, and good luck with the secret third option: being a governess. Thus, the amount of Victorian novels about unfortunate girls being unfortunate because they were, first and foremost, born girls is no surprise. Controversial, unappreciated, and “Fallen” women are prevalent here; some novels have happy endings, others not so much. If you want to feel grateful for being a woman in the 21st century, read this:

The Mill on the Floss - George Eliot

Jane Eyre - Charlotte Brontë

Ruth - Elizabeth Gaskell

Agnes Grey - Anne Brontë

The Odd Women - George Gissing

The Old Curiosity Shop - Charles Dickens

The Tenant of Wildfell Hall - Anne Brontë

Villette - Charlotte Brontë

Hester - Margaret Oliphant

Tess of the D’Urbervilles - Thomas Hardy

Sylvia's Lovers - Elizabeth Gaskell

Dombey and Son - Charles Dickens

Historical Novels

The English historical novel owes a lot to Sir Walter Scott, and several Victorian writers have tried to fill his shoes as his heir. What strikes me about the Victorian historical novel is the excessive English patriotic bias and the lack of commitment to facts. I don't condemn it so much because most historical novels of that period, in other countries, were written in the same somewhat fanciful way.

According to George Lukacs, Walter Scott is the only real historical novelist, Thackeray more or less, and he discards all the rest. I think it's pointless to look for a classic, static and pure form of the historical novel, because throughout the century, various aesthetic and thematic factors influenced the Victorian authors, and most of the time, a book fits into more than one subgenre.

I’m really excited to read Vanity Fair sometime soon:

Vanity Fair - William Thackeray

A Tale of Two Cities - Charles Dickens

Marius, the Epicurean - Walter Pater

Romola - George Eliot

The History of Henry Esmond - William Thackeray

Barnaby Rudge - Charles Dickens

Lorna Doone - R.D. Blackamore

Felix Holt - George Eliot

The Trumpet-Major - Thomas Hardy

Barry Lyndon - William Thackeray

Complicated Marriages and Sensitive Young Men

Marriage was a major issue in the Victorian era: lives and reputations depended upon it as well as one’s economic status (i.e. social mobility) and, in some cases, one’s happiness (especially if one dared to dream of marrying someone for love). Thus, a bad marriage was the obvious tragedy a writer could think of in the life of a Victorian young lady or gentleman. A bad Victorian marriage is usually accompanied by a sensitive young man, a rake, an irresistibly naive girl, a love triangle (or quartet) and some kind of money trouble. Ambition and disillusionment are central themes in these stories, and they end up in tragedy more often than not. I eat this up every single time, and I hope you will too:

The Egoist - George Meredith

The Woodlanders - Thomas Hardy

The Portrait of a Lady - Henry James

Daniel Deronda - George Eliot

Jude the Obscure - Thomas Hardy

The Return of the Native - Thomas Hardy

Great Expectations - Charles Dickens

The Professor - Charlotte Brontë

Roderick Hudson - Henry James

Can You Forgive Her? - Anthony Trollope

Provincial and Regional Novels

These novels are set in pastoral settings, aiming at a sentimental opposition between idealised country life and alienating city life. They can either be just a cute nostalgic tale or a scathing social critique (or even both). The region is a specific place in itself — there’s always an idiosyncratic identity related to the place — while the province is archetypal, a general setting defined by its opposition to the metropolis, aka London. This is my favourite type of Victorian novel due to its nostalgia, its natural descriptions (usually influenced by the Romantics such as Wordsworth), and its critique of industrialisation and harmful technologies.

As always, novels have multitudes and categorising them can be tricky. For example, although Middlemarch is a novel that deals heavily with the unhappiness brought about by equivocal marriages, it's not the general theme, as several other political and social issues are discussed with equal importance; above all, it's not a novel that ends in tragedy because of a bad marriage. I would say that Middlemarch can be placed in several categories, but because of the author's intention to determine many of the book's events from the emblematic village (and the subtitle is literally ‘a study of provincial life’), I have placed this book here.

Obs: I have included a couple of Anthony Trollope’s novels, but I’d say that most of his work (especially his Chronicles of Barsetshire) fall into this category.

Adam Bede - George Eliot

Far from the Madding Crowd - Thomas Hardy

Doctor Thorne - Anthony Trollope

Middlemarch - George Eliot

Cranford - Elizabeth Gaskell

The Doctor's Family - Margaret Oliphant

The Mayor of Casterbridge - Thomas Hardy

Silas Marner - George Eliot

The Warden - Anthony Trollope

Under the Greenwood Tree - Thomas Hardy

Miss Marjoribanks - Margaret Oliphant

Scenes of Clerical Life - George Eliot

Political, Industrial and Class Novels

The first half of the 1800s was a tough time in England: people (children included) working in factories with little to no regulation, the ‘hungry forties’ situation, and the New Poor Law of 1834 are important examples to contextualise this period. Again, the Victorian Era was marked by radical change in many aspects, and the social-political turmoils throughout the century always found a place in literature.

As a subgenre, the English social novel gradually disappeared as workers' conditions improved. For example, later novels exploring this theme were generally set in past decades or they addressed more ‘sophisticated’ political issues, such as legal disputes and bank fraud, as in The Way We Live Now. Thus, the condition novel is somewhat a victim of its own success, as novels exposing the tragedy of the working class exerted a great influence on the political scene, with Dickens' work being particularly noteworthy.

In addition to narratives about ‘the condition of England,’ this list includes books on social mobility problems, relationships between different classes, issues involving corruption and the English political system, etc.

Shirley - Charlotte Brontë

North and South - Elizabeth Gaskell

David Copperfield - Charles Dickens

The Nether World - George Gissing

Hard Times - Charles Dickens

Sybil: or The Two Nations - Benjamin Disraeli

The Way We Live Now - Anthony Trollope

Mary Barton - Elizabeth Gaskell

Little Dorrit - Charles Dickens

Alton Locke: Tailor and Poet - Charles Kingsley

New Grub Street - George Gissing

Orely Farm - Anthony Trollope

Nicholas Nickleby - Charles Dickens

Dark and Mysterious: Between Science Fiction and the Supernatural

Having studied the different phases and genres in the literature of 18th and 19th-century England, I disagree with summing up certain Victorian books as Gothic, as they would normally be better placed in other categories. What I think is appropriate is to say that such books have ‘Gothic elements,’ because a Gothic novel would actually be the works of authors such as Ann Radcliffe, Horace Walpole, Matthew Lewis, etc., that is, writers from the late 18th century who were working within the influences of Romanticism.

Several Victorian works have supernatural and dark elements, but Victorian authors usually go beyond these aspects to define their stories. Many science fiction novels even have elements of horror that would place them in this grey category called ‘Victorian Gothic’. In short, the traditional Gothic novel is very different from Victorian Gothic, which is more urban and subtle: the conventions are different because the fears of that society are different, such as the dread of atavism caused by Darwinist hypotheses and anxieties about foreigners with the decline of the British Empire.

The Turn of the Screw - Henry James

Wuthering Heights - Emily Brontë

The Picture of Dorian Gray - Oscar Wilde

Dracula - Bram Stoker

The Lifted Veil - George Eliot

The Island of Doctor Moreau - H.G. Wells

She - H. Rider Haggard

Carmilla - Sheridan Le Fanu

The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll & Mr Hyde - Robert Louis Stevenson

Bleak House - Charles Dickens

News from Nowhere - William Morris

III. Making the Most of the Right Edition

Much of my reading experience depends on the edition I have in hands. To this day, I don't think I enjoyed Jane Eyre as much as I could have because I read it in the Penguin Popular Classics edition, a paperback made of cheap paper, with a tiny font and no notes or introduction. That was at the beginning of my reading career, and I didn't yet know the differences between editions.

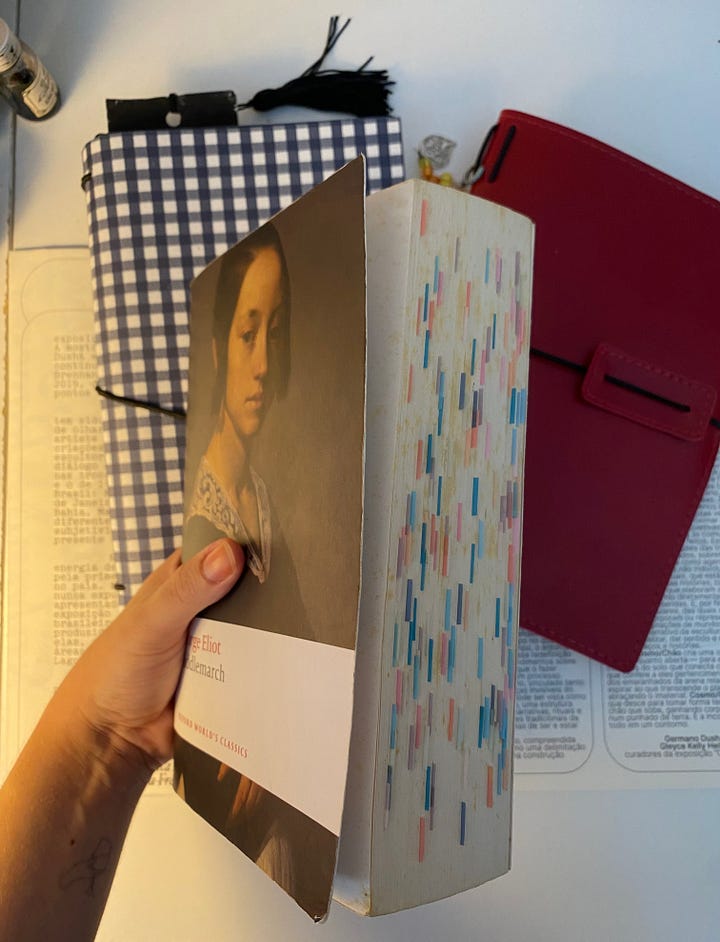

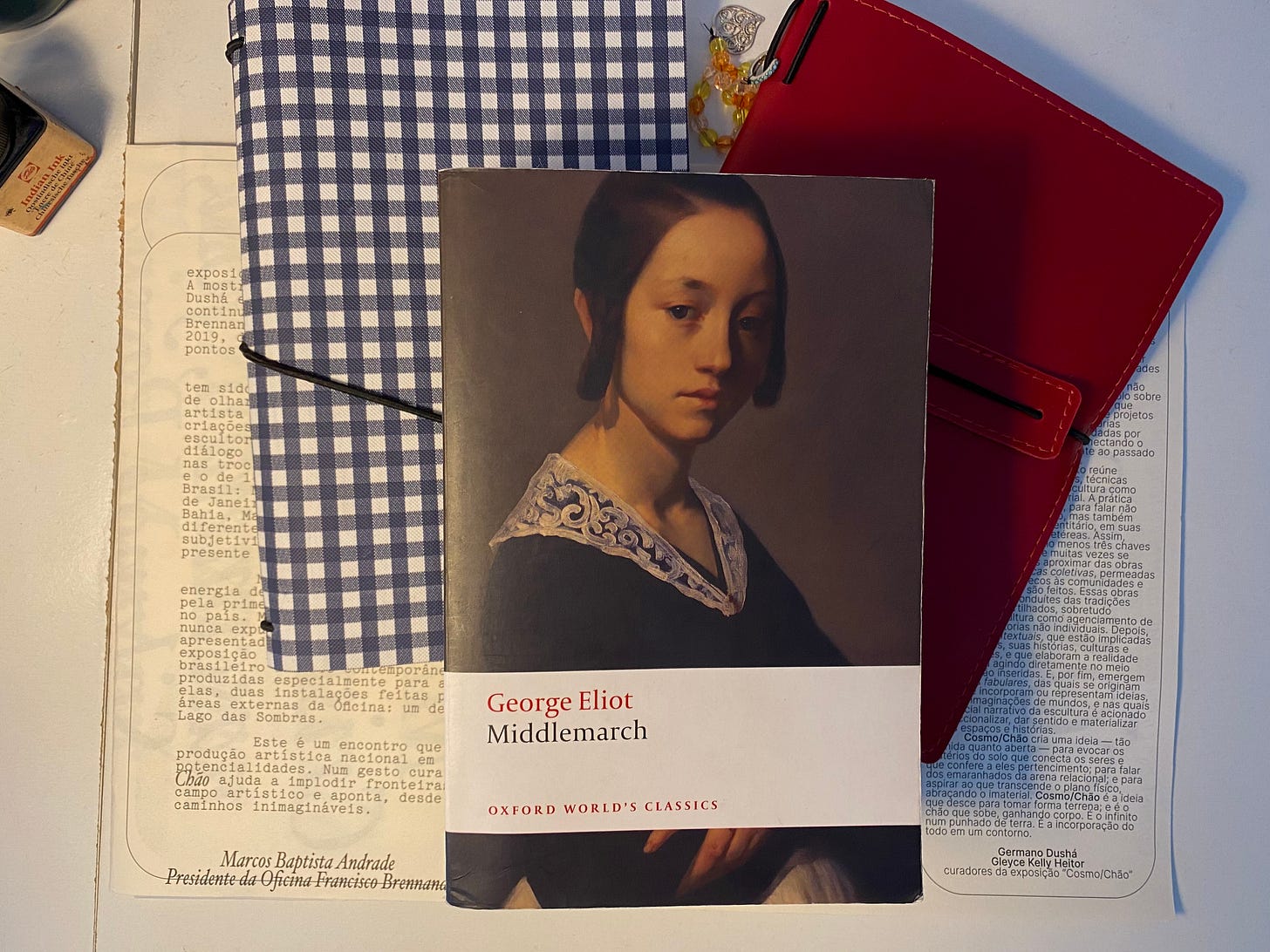

Nowadays, I tend to buy Victorian literature only in the Oxford World's Classics or Penguin Classics (Black Spine) editions, with a few rare exceptions (such as Norton for academic research and Everyman’s Library for collecting), for the following reasons:

Paper quality, in terms of tactile feel and the book's resistance to wear and tear

Appropriate font size and spacing

Excellent explanatory notes at the end

Comprehensive bibliography (don’t underestimate this section for research fonts)

Thorough introductions written by scholars in the field (which I never skip, even if I save it for later)

Good space in the margins for annotations

Aesthetically pleasing (every classic book cover should have a painting)

Now I will show you my most detailed annotation method using Middlemarch, one of my most annotated books, as an example. I don’t do this with all books (because it would be impossible), only with those that I want to analyse more deeply.

**It’s important to establish that I do this for fun. It’s not stressful or difficult for me. It’s an activity I thoroughly enjoy; otherwise I would never give myself the trouble.

Step 1: Establish an Annotation System

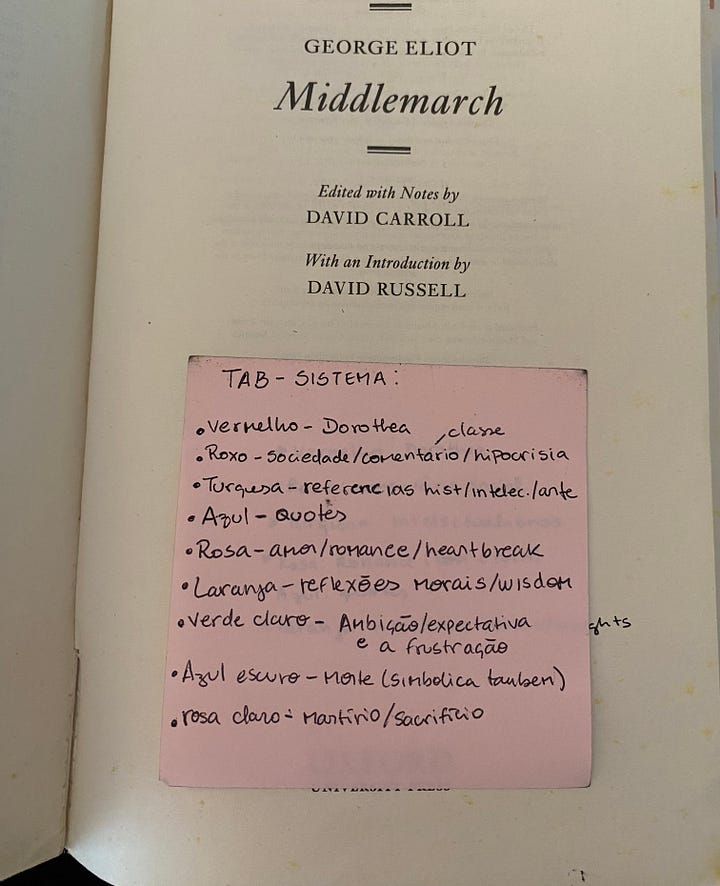

When I want to study a novel, this is my go-to annotation system. I think it’s quite simple; it only requires commitment and a little bravery concerning spoilers.

If I don’t already know what I want to look for in the novel, I search the novel’s major themes on the internet and select what interests me (that’s why I mentioned spoilers, because you’ll probably see some in this research — but I don’t mind them at all).

I use coloured tabs, selecting a different colour for each theme. In the book’s first page, I’ll write down this colour system so I don’t forget. For Middlemarch, my system was as follows: red - Dorothea; purple - social/class commentary; turquoise - art/history references; blue - favourite quotes; pink - love/romance/heartbreak; orange - wisdom/moral reflections; light green - ambition/disillusionment; dark blue - death/rebirth; light pink - martydom/sacrifice;

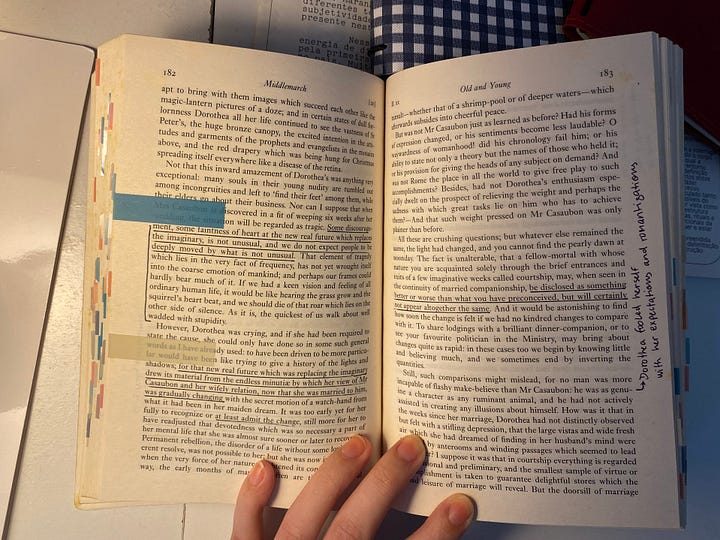

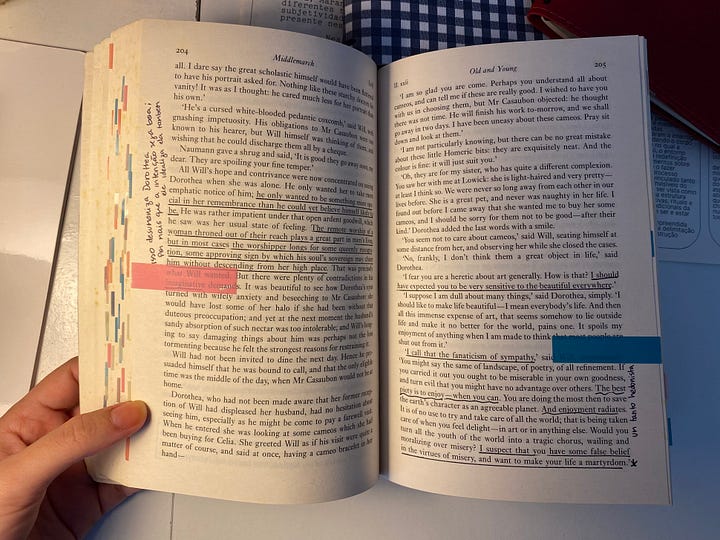

This system also pushes me to read attentively, so once I come across one of these aspects, I mark them. I also write in the margins some thoughts or associations that I can later develop in my reading journal.

Step 2: Get a Reading Journal

I use Notion for this, but there are dozens of ways you can build a space for your book annotations: it can be in a physical notebook, in a word doc, in your notes app… the important thing is to have a specific space for this

Then, I will organise my notes based on the novel’s division into parts and/or chapters. For example: Middlemarch is divided into eight books, so my notes followed this division. Every time I finished a book, I would write in two different sections: References and Impressions

The ‘references’ section is dedicated to signalling and explaining to myself some allusions or mentions made by the author. George Eliot, as an extremely knowledgeable woman, fills her books with references to artworks, philosophical theories, historical facts, etc., and if I really want to learn from her, I must research what the hell she is talking about. In the first Book, for instance, Eliot mentions Thomas Dekker’s The Virgin Martyr, so I highlighted it in the text to research later (as you can see in the image above).

My reading journal is written in collaboration with my own highlights and annotations made in the physical copy. If I don’t annotate in the book, there’s nothing to write in the reading journal. I always say that I can’t read without a pen in hand.

Don’t forget to use the endnotes in your edition to complement your annotations.

The ‘impressions’ section is written freestyle-freethinking-stream-of-consciousness as soon as I’m done with the established portion of the book. Here is an example of what I wrote when I finished Middlemarch’s Book I (it’s in Portuguese, my native language). This is a moment to let your brain work without concerning itself with form, repetition, or even making sense. If you’re planning on writing an essay on the book later, you’ll be surprised by how useful this material can be, since you’ll likely forget all of your little ideas if you leave the reflection for later.

Step 3: Concluding Thoughts

Since I have an Instagram page where I post reviews of everything I read, I already have a habit of sitting down to organise my thoughts about a book once I have finished reading it. So I encourage you to do the same and write at least a paragraph summarising your reading experience. This helps to consolidate your opinion, to remember why you liked (or didn't like) it, and trains your critical thinking skills and ability to articulate ideas, which, after all this annotating, will be well-founded.

IV. A Victorian Syllabus

After finding the Victorian novels, short stories, and poems that suit your taste, you may fall in love with a particular genre or author (hopefully!) and want to delve deeper and research them. With that in mind, I have put together a syllabus based on books I liked and books featured in the syllabi of leading English-speaking universities such as Oxford and Yale, among others.

Here you will find 95 items — including books, authors, and academic journals — to explore according to your interests. You may notice the bias of my area of interest within the Victorian Era, which is gender and marriage issues.

A tip for finding texts on a particular aspect (such as politics, colonialism, or horror) is to look in the ‘Further Reading’ or ‘Bibliography’ section of the edition of the novel you are interested in researching (always present in Penguin Classics and Oxford World's Classics editions).

Understanding Victorians through Victorian Authors

Matthew Arnold: Culture and Anarchy (1869)

Charles Darwin: The Origin of Species (1859); The Descent of Man (1871)

John Ruskin: Unto This Last and Other Writings (Penguin edition); The Seven Lamps of Architecture (1849);

Oscar Wilde: The Decay of Lying (1891); The Critic as Artist (1891)

John Stuart Mill: On Liberty (1859)

John Henry Newman: An Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine (1845); The Idea of a University (1852)

George Eliot: Selected essays, poems and other writings (Penguin edition)

William Morris: News from Nowhere (1890)

George Saintsbury: A History of Nineteenth Century Literature (1780–1895) (1896)

Thomas Carlyle: Past and Present (1843)

Victorian Era: An Overview

Terry Eagleton: The English Novel: An Introduction (2005)

Robin Gilmour: The Victorian Period: The Intellectual and Cultural Context of English Literature (1993)

A. N. Wilson: The Victorians (2002)

Matthew Sweet: Inventing the Victorians (2001)

Richard D. Altick: Victorian People and Ideas (1973)

Raymond Williams: The English Novel from Dickens to Lawrence (1970)

Isobel Armstrong: Victorian Poetry: Poetry, Poetics and Politics (1993)

F.R. Leavis: The Great Tradition (1948)

G.K. Chesterton: The Victorian Age in Literature (1913)

Arnold Kettle: An Introduction to the English Novel, Vol. I & II (1951, 1953)

The Woman Question: Gender, Sexuality, and Feminist Criticism

Nina Auerbach: Woman and the Demon (1982)

Sandra M. Gilbert and Susan Gubar: The Madwoman in the Attic (1979)

Pamela K. Gilbert: Disease, Desire, and the Body in Victorian Women’s Popular Novels (1997)

Sharon Marcus: Between Women: Friendship, Desire, and Marriage in Victorian Literature (2007)

Patricia Ingham: The Language of Gender and Class (1996); Dickens, Women and Language (1992)

Kate Flint: The woman reader (1837-1914) (1993)

Phyllis Rose: Parallel Lives: Five Victorian Marriages (1983)

Françoise Basch: Relative Creatures: Victorian Women in Society & the Novel (1974)

Phillippa Levine: Victorian Feminism (1850-1900) (1997)

Ben Griffin: The Politics of Gender in Victorian Britain: Masculinity, Political Culture, and the Struggle for Women’s Rights (2012)

Amanda Anderson: Tainted Souls and Painted Faces: The Rhetoric of Fallenness in Victorian Culture (1993)

Elizabeth K. Helsinger: The Woman Question: Society and Literature in Britain and America 1837–1883 (1983)

Elaine Showalter: A Literature of Their Own (1977)

Mary Poovey: Uneven Developments: The Ideological Work of Gender in Mid-Victorian England (1988)

Sally Ledger: The New Woman: Fiction and Feminism at the Fin de Siècle (1997)

Aspects of Realist Fiction: Science, Philosophy, Historicism and Intellectual History

Avrom Fleishman: The English Historical Novel (1971)

Elizabeth Deeds Ermarth: Realism and Consensus in the English Novel: Time, Space and Narrative (1998)

Brian Hamnett: The Historical Novel in Nineteenth-Century Europe: Representations in History and Fiction (2011)

Peter Brooks: Realist Vision (2005)

John Holloway: The Victorian Sage: Studies in Argument (1953)

Camilla Cassidy: Twilight Histories: Nostalgia and the Victorian Historical Novel (2023)

Robin Gilmour: The Victorian Period: The Intellectual and Cultural Context of English Literature (1993)

Spirituality and Aesthetics: from the Pre-Raphaelites to the Decadent Movement

James Eli Adams: Dandies and Desert Saints: Styles of Victorian Manhood (1995)

Catherine Maxwell: Second Sight: The Visionary Imagination in Late Victorian Literature (2012)

Kate Flint: The Victorians and the Visual Imagination (2000)

Hilary Fraser: Beauty and Belief: Aesthetics and Religion in Victorian Literature (1986)

Tim Barringer: Reading the Pre-Raphaelites (1999)

Karl Beckson: Aesthetes and Decadents of the 1890s: An Anthology of Poetry and Prose (2012)

Holbrook Jackson: The Eighteen Nineties: A Review of Art and Ideas at the Close of the Nineteenth Century (1913)

U. C. Knoepflmacher: Religious Humanism and the Victorian Novel (1965); Victorians Reading the Romantics (2016)

Matthew Sturgis: Passionate Attitudes: English Decadence of the 1890s (1995)

John Dixon Hunt: The Pre-Raphaelite Imagination, 1848–1900 (1968)

Politics, Empire, Race, and Postcolonial Studies

Stephen Ingle: Narratives of British Socialism (2002)

Duncan Bell: Victorian Visions of Global Order (2007)

David Cannadine: Ornamentalism: How the British Saw Their Empire (2001)

J.A. Hobsbawm: The Age of Empire, 1875–1914 (1989)

Seth Koven: Slumming: Sexual and Social Politics in Victorian London (2006)

Anthologies and Companions

Oxford’s Authors in Context Series

Oxford’s A Very Short Introduction series

The Routledge Companion to Victorian Literature

James Eli Adams — A History of Victorian Literature - Blackwell Histories of Literature (2011)

Deirdre David (ed.) — The Cambridge Companion to the Victorian Novel (2001)

Francis O’Gorman (ed.) — The Victorian Novel: A Guide to Criticism (2002)

Francis O’Gorman (ed.) — A Concise Companion to the Victorian Novel (2005)

John Sutherland (ed.) — The Stanford Companion to Victorian Fiction (1989)

Late Victorian Gothic Tales (Oxford World's Classics)

Victorian Fairy Tales (Oxford World's Classics)

The Penguin Book of Victorian Verse

The Penguin Book of Victorian Women in Crime

Victorian Women Poets 1830-1901: An Anthology (Everyman's Library)

Literature and Science in the Nineteenth Century (Oxford World’s Classics)

Further Resources: articles, websites, academic journals, etc.

Websites for Research:

Internet Archive (you can find many books listed there)

JSTOR (THE place to find academic articles)

At the Circulating Library: A Database of Victorian Fiction, 1837-1901

Academic Journals:

Victorian Literature and Culture (ISSN: 1470-1553)

Journal of Victorian Culture (ISSN: 1355-5502)

Victorian Studies (ISSN: 1527-2052)

Bronte Studies (ISSN: 1745-8226)

Dickens Quarterly (ISSN: 2169-537)

Nineteenth-Century Fiction

Random Articles I Recommend:

“Christina Rossetti and Commonplace Books” - Christopher Ricks

“Culture and Environment: From Austen to Hardy” - Jonathan Bate

“Double Gender, Double Genre in Jane Eyre and Villette” - Robyn R. Warhol

“The Post-Romantic Imagination: Adam Bede, Wordsworth and Milton” - U. C. Knoepflmacher

"Middlemarch": The Genesis of Myth in the English Novel - Felicia Bonaparte

“Pre-Raphaelite Challenges to Victorian Canons of Beauty” - Susan P. Casteras

“Spirited Sexuality: Sex, Marriage, and Victorian Spiritualism” - Marlene Tromp

“The Art of Looking Dangerously: Victorian Images of Martyrdom” - Maureen Moran

I hope you enjoyed this extremely laborious post and found something useful. I will be back with other guides.

i love this post sm btw and all of the hard work you put into this. i often revisit to read & browse some of the titles you have included 💛

Wow, this is LOVELY. thank you! adding a lot of titles I haven't read before to my tbr list.

so excited to find my man Henry James here - so glad you included his work. definitely subscribing.