Shakespeare's Plays - Reading Guide #1

everything you need to become an independent Shakespeare student

“Shakespeare was the strongest manifestation, the psychic message of a whole generation, expressing through the senses, a time turned passionately enthusiastic” — Stefan Zweig

‘How do I start reading Shakespeare?’ —or a variation of this— is probably the question I get asked the most, either here or on my bookgram. I always try to respond in the best way I can, but it’s not always possible to give every answer.

So inspired by that, I decided to begin a series of reading guides, and the first one had to be about the wonderful William Shakespeare, my special interest, the author who inspired me to start writing literary criticism and this newsletter (the name ‘Methinks’ is, of course, a reference to him), and the birthday boy — today is April 23rd, Shakespeare’s (supposed) birthday, so it was only fitting that I should post this guide today.

I hope you find this useful, happy reading!

I. Shakespeare contains multitudes

Shakespeare is one of the most versatile writers in the history of literature, with 38 plays that encompass a myriad of human emotions and experiences, deeply rich characters and unique stories, alongside the most clever use of the English language.

Before we start, I must preface this guide by saying this: it’s ok to not like Shakespeare. Do I think he’s the greatest writer who ever lived? Yes, but that’s just me (and Harold Bloom). If you gave an honest attempt at reading his plays and they didn’t resonate with you, it’s ok, it happens. Sometimes we feel like we must enjoy certain works or authors just because they have this canonical status, but it’s 2025, and I believe we can leave this dated, Leavis-esque beliefs behind. Trust your taste, and if you don’t know your taste yet, it’s time to find out through trial and error.

So if you want to try Shakespeare and don't know where to start, I am positive you can find at least one play that fits your particular interests, and I can help you with that. Shakespeare’s plays are usually divided by genres: Tragedy, Comedy, Histories and Romances (a sort of tragicomedy). The idea here is that you find something you might like to start with and expand from there.

My favourite plays are Hamlet, King Lear, and Henry IV parts 1 & 2, in this order. To me, Shakespeare is at his best when he deals with heavy drama, strong characters and bitter endings. I enjoy his comedies, but they never captivate me the way his tragedies do. I have read about half of his work (and I’m afraid of the day there won’t be any ‘new’ play left) and I don’t like all of it, but I know enough about them to give you informed recommendations.

So, without further ado:

The Most Accessible

If you haven’t read anything by Shakespeare and don’t know what you like or where to start, I’d recommend these due to their accessibility (either because of the plain context, the straightforward/engaging plot, or just the sheer amount of fun):

Julius Caesar (historical tragedy)

Othello (tragedy)

Much Ado About Nothing (comedy; my favourite comedy, by the way)

The Comedy of Errors (comedy)

The Winter’s Tale (romance)

A Midsummer Night’s Dream (comedy)

Romeo and Juliet (tragedy; p.s.: I don’t like this play, but most people do so go off)

If you prefer external to internal turmoil and don’t mind a bit of violence…

The following plays are more plot-driven, so try to keep up. Some of them benefit from historical context, but a good edition will provide that in the introduction. If you’re someone who enjoys high fantasy novels, action movies, thrillers and political intrigue, read one of these:

Titus Andronicus (historical tragedy)

Henry V (historical tragedy*; although this one is not exactly a tragedy)

As You Like It (comedy)

Cymbeline (romance)

King John (historical tragedy)

Troilus and Cressida (tragedy)

Pericles (romance)

If you like movies that make you cry, existential crises, psychological narratives and Greek dramas…

These are the ones that have made a lasting impression on me (and also made me sob). The fact that my three favourites are in this category says a lot about my taste in literature (for example, I love Thomas Hardy and think Anna Karenina is the best book ever written). Of these, I find King Lear the most devastating — I felt really bad when I finished reading it. These are more difficult and psychologically complex plays, so read them knowing that further reading will be quite useful:

Coriolanus (historical tragedy)

King Lear (tragedy)

Hamlet (tragedy)

Henry IV part 2 (historical tragedy)

Anthony and Cleopatra (tragedy)

If you like weird narratives, miscommunication tropes, unlikable characters and had a manic-pixie-dream phase…

This is probably the most mismatched list I've made. What unites these plays is their individuality, originality, a touch of quirkiness and rather confusing narratives. Perhaps it's surprising that Richard II is here, but it stands out among the English Histories for its lack of action and adventure. It's an existential drama with a somewhat mystical ending; the comedies listed have identity swaps and the famous miscommunication trope; the romances are fanciful and strange. If you'd like to get to know the Shakespeare B-side, read these:

Richard II (historical tragedy)

Timon of Athens (historical tragedy)

The Tempest (romance)

Love’s Labour’s Lost (comedy)

All's Well That Ends Well (comedy)

Twelfth Night (comedy)

The Merry Wives of Windsor (comedy)

The Two Noble Kinsmen (romance)

If you are a nerd who has niche obsessions, enjoys courtroom dramas and is a fan of Tolkien, Mantel or Martin…

This is probably my favourite Shakespearean niche. It's for those who (like me) enjoy history podcasts and 3-hour video essays on YouTube. If you're prone to going down rabbit holes on Wikipedia: good, you'll need it for English histories. I love the Henriad tetralogy (Richard II, Henry IV 1 & 2, Henry V) and it's my mission in life to spread the word about it. You'll find plenty of plays here that benefit from historical research and have influenced many of the high fantasy novels and TV shows we have now.

Macbeth (tragedy)

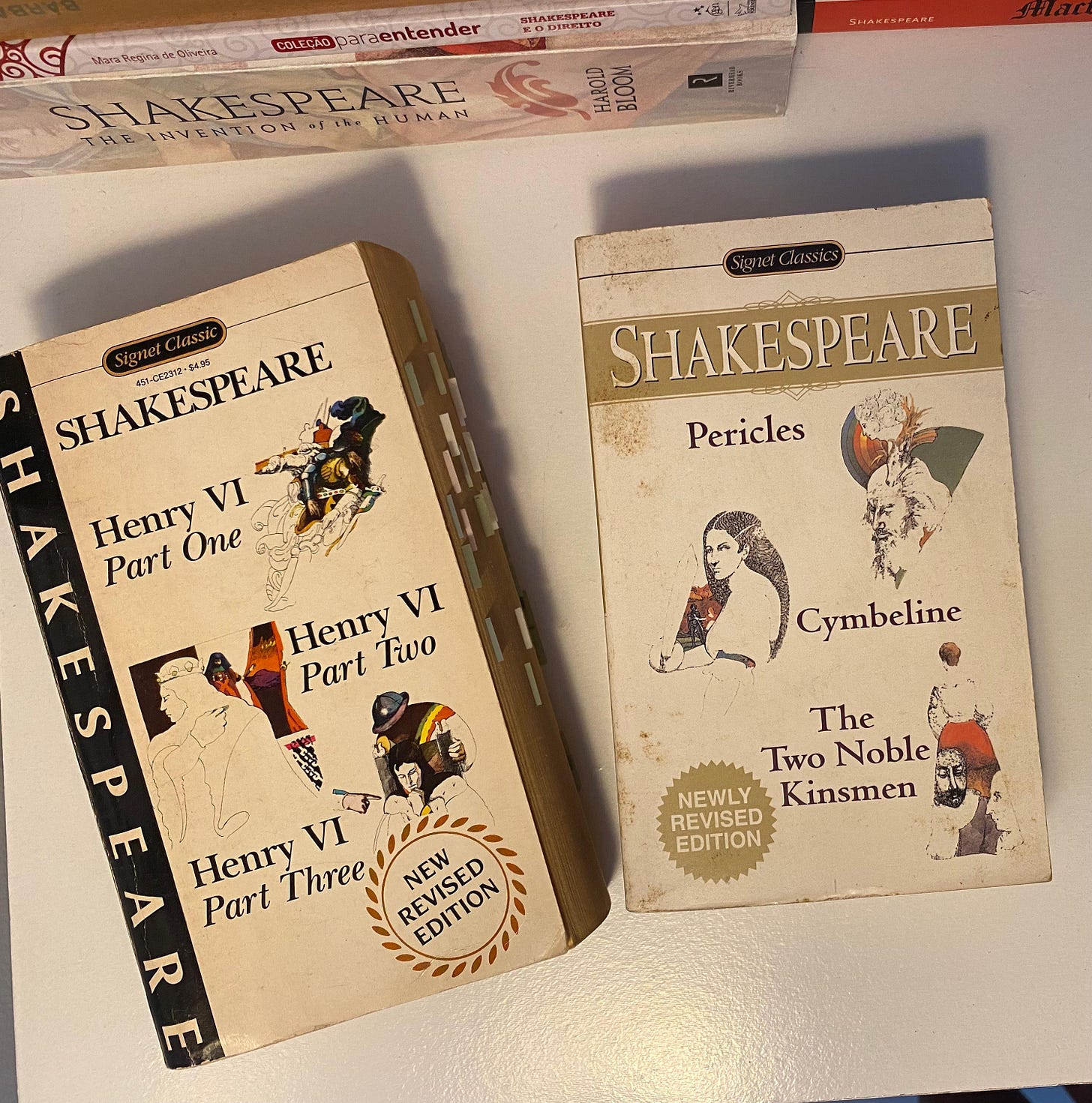

Henry VI parts 1,2 & 3 (historical tragedy)

Henry IV part 1 (historical tragedy)

Richard III (historical tragedy)

The Merchant of Venice (comedy)

Measure for Measure (comedy)

Henry VIII (historical tragedy)

II. Finding the right edition

A good critical edition is indispensable to assist your reading experience, especially if you are new to the world of Shakespeare or, like me, enjoy deeply analysing everything. I've read the plays in various editions and can now confidently recommend some of them. I usually buy used books, so just know that you don't have to spend a lot to get a good edition.

But first, a few general tips:

Don't skip the introduction: no Shakespeare play will suffer from spoilers. Always read the introduction first, because most of the time this contextualisation fills in a lot of gaps in the reading experience and you won't get confused. Many tacit understandings between Shakespeare and his audience are lost to us now, so it’s good to know what you’re dealing with beforehand.

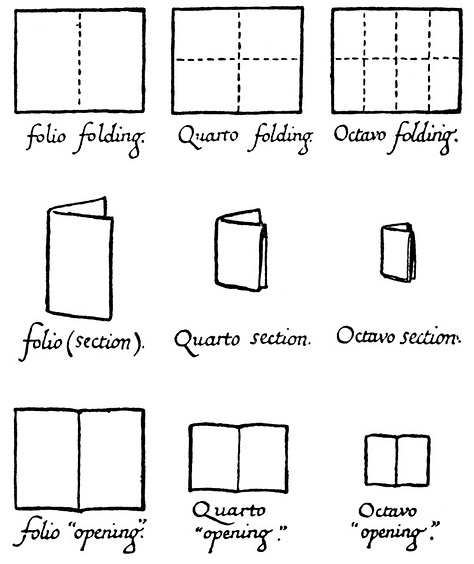

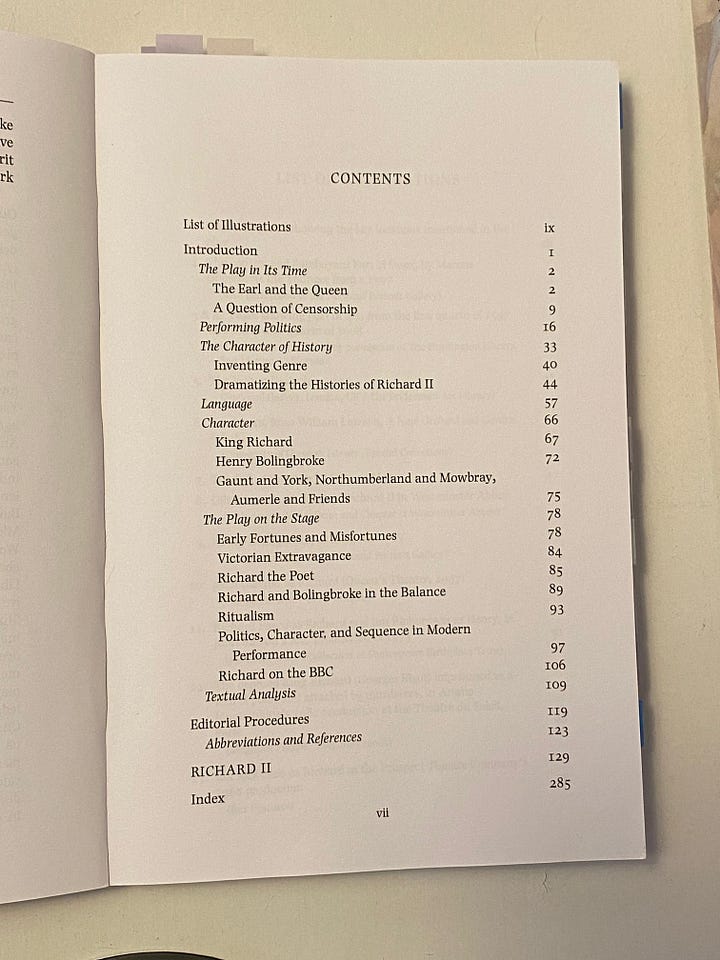

Do not — under any circumstances — skip the ‘Editorial Procedures’ section or ‘A Note on the Text’ or something similar. These sections explain the methods used by the editors in preparing the text, regarding the modernising of spelling, changes to the original text, filling in gaps, discrepancies between versions, etc., leading up to the final version you have in your hands. Shakespeare’s plays usually have more than one ‘original’ text to serve as a base, for example, there are three main texts of Hamlet: the First Quarto (Q1), the Second Quarto (Q2), and the First Folio (F1), and in the editorial procedures, the editors explain which one did they use (or combine) to get to the present version in print. This terminology refers to early modern printing methods: a quarto is a smaller book format in which a printer folds a sheet of paper twice, producing eight pages per sheet, and they were unofficial publications usually used or written by the actors; a folio is a larger book format in which a sheet of paper is folded once, creating four pages per sheet. Editors compare quartos and folios to reconstruct the most accurate versions of Shakespeare’s plays.

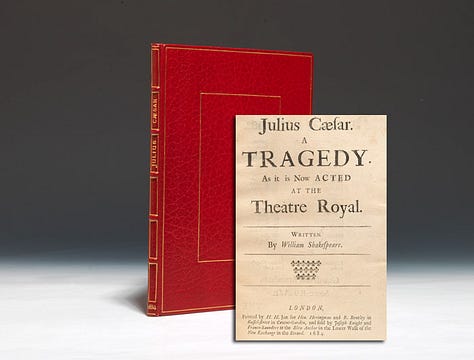

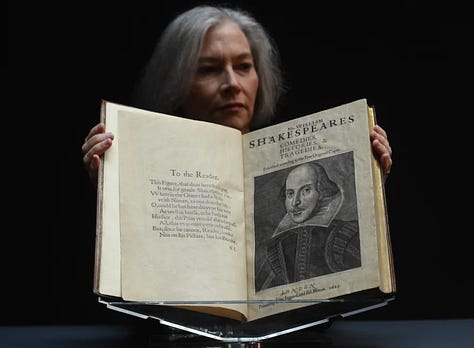

Image 1: illustration of the difference between quartos and folios; Image 2: A Slim Quarto of Julius Caesar printed by H. H. Jun. for Hen. Heringman and R. Bentley in 1684; Image 3: a copy of The First Folio of Shakespeare's complete plays, published in 1623 by the actors John Heminge and Henry Condell, friends of the Bard. A quick info about this: 16 of Shakespeare’s plays were first printed in quarto form (1594 to 1622) before the publication of the 1623 First Folio (pictured above); of the 20 plays which made their first appearance in the First Folio, only 3 appeared in quarto form during the 17th century: The Taming of the Shrew and Macbeth (each in one quarto edition) and Julius Caesar (in six quarto editions), which are possible testaments of their popularity and endurance.

Read the footnotes and/or endnotes: Don’t be lazy ok, you’ll thank me later. Good editions provide context and potential interpretations of important scenes or lines in these notes, they are there for a reason.

Check the ‘Further Reading’ section: editors, like university students, also have a responsibility to include references to their work. I've built up a large repertoire and found some great academic sources by checking this part of the books. Often, people don't know where or how to find good critical texts — start there.

Without further ado, the editions:

The Oxford Shakespeare

My all-time classic for a reason. I worked with the Oxford edition of Richard II for my honours thesis, and it was the best choice. Oxford editions come with an extremely thorough introduction, usually divided into thematic topics, an extensive bibliography, appendices, and the editorial procedures section is always very detailed. As the Oxford editions are a little too complete, with intimidating introductions of over 100 pages, I would only recommend this one if you're really going to study the play, otherwise, a slightly simpler edition is more than enough.

By the way, this year they are reissuing the plays under the title ‘The New Oxford Shakespeare’ with updated criticism; I can’t wait to get a new copy of Richard II and see if there are any new interpretations.

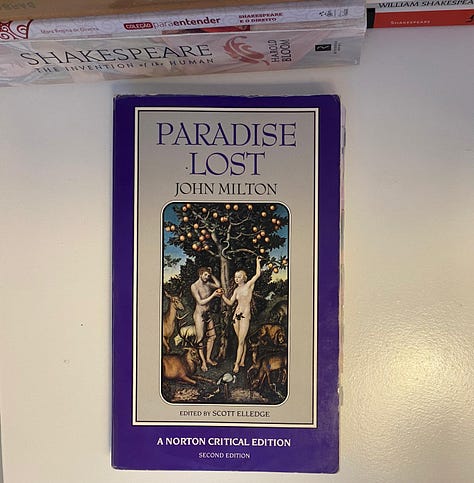

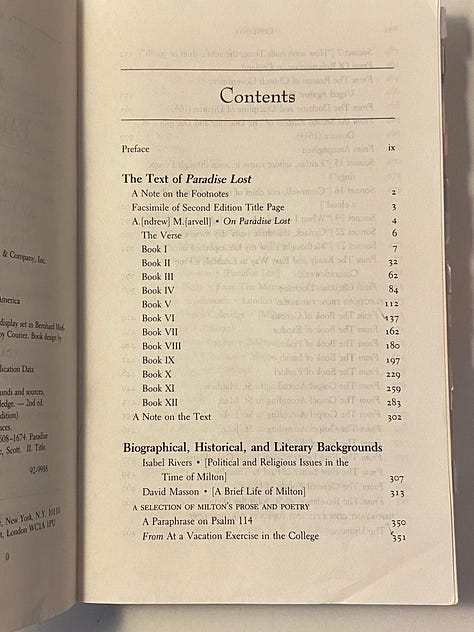

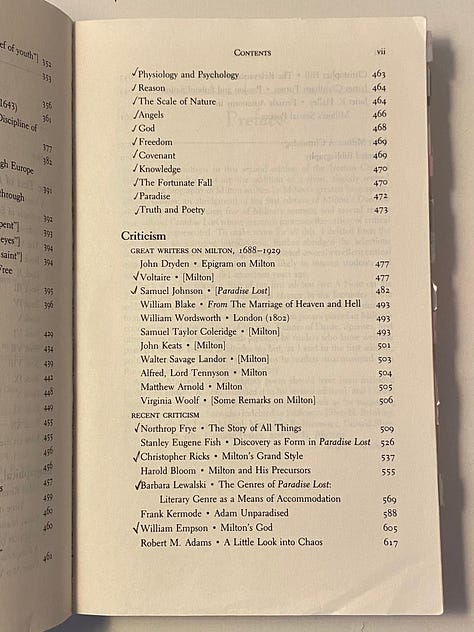

The Norton Critical Editions

The Norton edition is excellent, but I believe it only works for very specific readers. This edition can be too complete, to the point where I feel guilty to this day for not having read all the critical texts contained in my copy of Paradise Lost. I don't own a Norton Shakespeare play, as I think it's only worth buying this edition if you're already very interested in the play and want to study it in depth, as the amount of supporting material inside the book is both amazing and daunting. The only Shakespeare work I'm keen to buy in this edition is Hamlet, because I'm completely (ridiculously) obsessed with this play and I don't think I'll ever know enough about it.

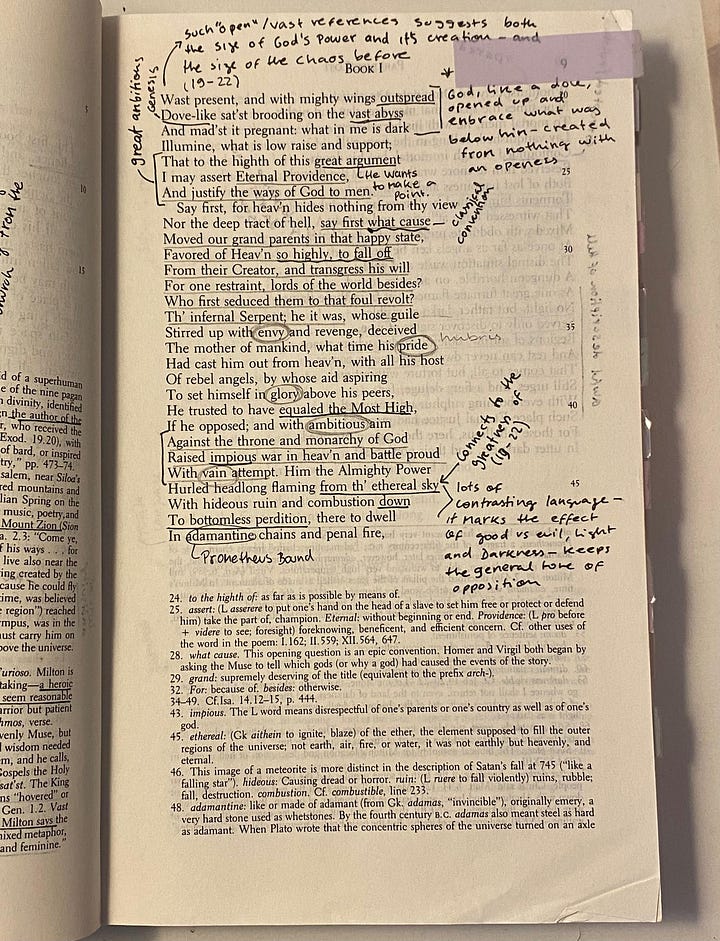

Here's a picture of my edition of Paradise Lost to give you an idea of what it looks like:

The New Penguin Shakespeare

These are lovely pocket paperbacks from the late 1960s. I love them because they are very portable and sufficiently detailed, with introductions written by esteemed professors, a ‘play in performance’ section, genealogical tables and extensive commentary. Probably the best one for a beginner who is just curious enough to know more but doesn’t want to be overwhelmed. The penguins are, in my opinion, the most didactic editions (do not mistake them with the new Pelican Shakespeare; when in doubt, go for older editions or the black spine classics).

The Penguin Shakespeare series, edited by Stanley Wells and illustrated by Clare Melinsky

My favourite edition! I am obsessed with them and try to collect them all, but they are so hard to find. The ones I own are my most prized possessions, especially my Hamlet. They are very similar to the New Penguin Shakespeare ones and have the same level of academic and critical complements, but newer (from the early 2000s) and more stylish.

Singet Classics

The most affordable and easiest to find on this list. Don’t be fooled by its mass-market paperback layout: these editions are far from cheap. Not my favourite, but they all come with classic critical texts, from writers like Samuel Johnson and A.C. Bradley, instead of contemporary criticism, which can be interesting. I don’t recommend it if you want to actually study the play, since in such cases it’s better to know the current academic views instead of classic literary ones. A simple yet effective edition.

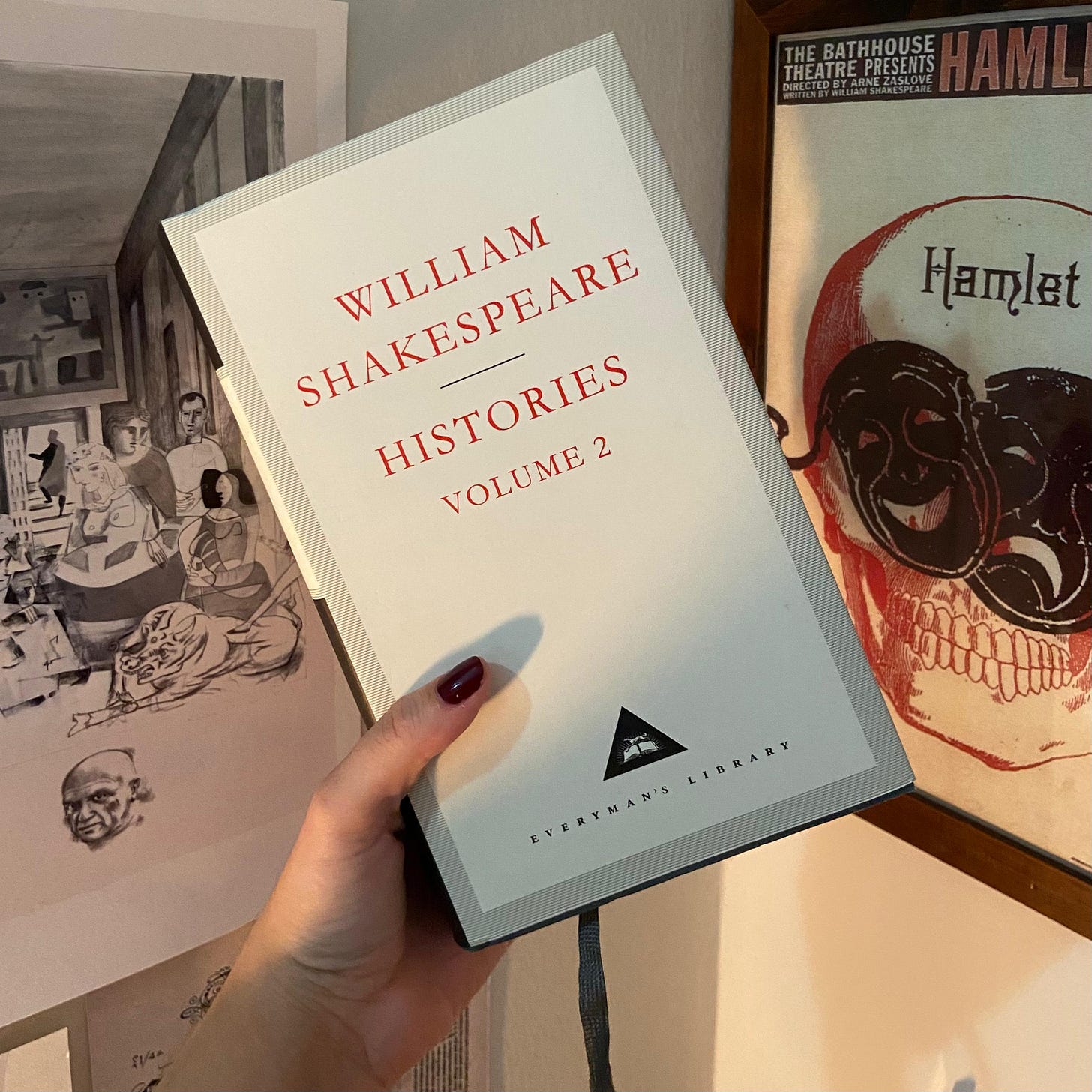

Everyman’s Library

A beautiful, fancy edition that will last a lifetime. Hardcover with simpler notes and introductions compared to the others. Everyman’s Library publishes Shakespeare’s plays in big volumes: Tragedies vol. 1 & 2; Comedies vol. 1 & 2; Histories vol. 1 & 2; Romances; Sonnets & Narrative Poems.

They're a bit expensive, but as you can get at least five plays in one volume, it ends up being a good deal (although it's not very portable, which can be a problem if you, like me, carry a book everywhere). I have ‘The Histories’ vol. 2, which contains Richard II, Henry IV parts 1 & 2, Henry V and Henry VIII. This book is one of the things I’d save in a fire: I have a profound, loving obsession with Shakespeare’s English Histories and this edition is so special to me. It was a Christmas present I gave to myself in 2022 during a trip to Rio, and now it’s heavily annotated. If you have a friend like me, a volume of Shakespeare from the Everyman's Library would be a wonderful gift.

The Royal Shakespeare Company (RSC) edited by Jonathan Bate and Eric Rasmussen

Sir Jonathan Bate is my favourite Shakespeare scholar, and he edited a whole series for the Royal Shakespeare Company. I read ‘The Winter’s Tale’ in this edition and totally enjoyed it. I think it’s at the same level as the penguins, so I’d recommend both for people who want to know more but are not actually studying the play.

Penguin Classics Shakespeare

Probably the easiest to find in bookshops, but careful not to mistake the classic black spine edition with the new colourful Pelican Shakespeare ones: I did not like them and I don’t trust as much as the older ones. I absolutely love the classic penguins for philosophy and poetry because they are so didactic — these editions have more explanatory notes than all the others. However, if you don't feel confident in your own intellectual views yet, this edition may hinder the development of an individual interpretation due to the amount of explanations.

This advice applies to every academic text you read, but take it with a grain of salt and abuse of your critical thinking skills: don't accept everything as absolute truth just because the person speaking has a PhD. However, don't think that you're free to indulge in any assertion just because literature isn't science. You need to find a nuanced balance and respect your views as well as the views of those who dedicate their lives to studying this. Read everything and value your own conclusions, as long as they are properly grounded; you have to maintain a certain methodological rigour — there's no use saying that Hamlet is mad without being able to explain why.

*Translation Section*

This is for my Portuguese-speaking readers. I have bad news.

Vou usar uma experiência pessoal de exemplo. Minha dissertação da graduação foi sobre Richard II, e seguindo a prática acadêmica da minha universidade, eu deveria trabalhar com a peça traduzida. Pois bem, eu tenho o box da editora Nova Fronteira traduzido por Bárbara Heliodóra e pretendia trabalhar com essa tradução. Li a peça em inglês quando tive a ideia para a tese, então tinha apresentado uma proposta ao meu orientador baseada em evidências textuais contidas no idioma original. Para minha terrível surpresa, a tradução de Bárbara não era só ruim como errada, pois vários argumentos que eu tinha elaborado a partir do texto original não faziam o menor sentido na tradução dela. Troquei para a tradução do Carlos Alberto Nunes da editora Peixoto Neto — melhor que a de Bárbara, mas ainda errada. Não encontrei uma terceira tradução dessa peça (como é o caso com as peças menos lidas no Brasil). Não lembro mais os exemplos de erro, mas foi tão grave que meu orientador pediu para eu reescrever meu TCC usando a peça em inglês (ainda bem que eu estava no começo) e colocar uma tradução autoral na nota de rodapé — e foi o que fiz.

Tudo isso para dizer que, até onde eu sei, não temos muita sorte com traduções de Shakespeare (um dos meus sonhos profissionais é traduzir Shakespeare para o português pois sou pretensiosa o suficiente para achar que eu conseguiria fazer certo com o devido estudo). Temos pouca variedade de tradutores no mercado, e a maioria do que já li traduzido eu não recomendo. Não estou falando isso querendo desmerecer o trabalho alheio nem querendo sinalizar superioridade intelectual por ler no inglês original.

Primeiro que eu não nasci sabendo; comecei lendo Shakespeare em traduções insatisfatórias mas não desisti (porque eu juro que dá vontade de desistir) e me esforcei para conseguir ler em inglês — e no fim das contas, nem é tão difícil quanto parece. Como tudo na vida é só uma questã de prática e costume com a linguagem Shakespeariana. Vocês sabem que tem certas coisas no mundo que são meio intraduzíveis (por exemplo, Clarice Lispector), e muito da genialidade de Shakespeare está justamente na inventividade textual e no jogo de palavras que só pode ser verdadeiramente apreciado em seu idioma original. A única tradução para o português que eu li e recomendo até hoje é a que Millôr Fernandes fez de Hamlet. Fora isso, por confiar na editora Penguin-Companhia como um todo, eu escolheria as traduções deles apesar de não ter lido.

Se você fala inglês eu diria, honestamente, tente ler as peças no original. É só um livro, se você achar impossível desista e pronto, não há mal nenhum nisso — mas eu prometo que vale muito a pena insistir. Poucas coisas me dão mais prazer do que ler Shakespeare, como já devem ter percebido.

III. Not a closet drama

This is the most important topic because knowing how to read actively, not passively, is the key to understanding a play thoroughly. Active reading means going beyond just reading silently; there's nothing wrong with that, but I think Shakespearean works benefit greatly from a more engaged participation on the reader’s part. These are the methods I use and recommend (yes, I really do all this, but not with all books, just Shakespeare's plays and books I want to study or write about afterwards):

Annotate by engaging with the text, as if you were talking to the characters or responding to the author;

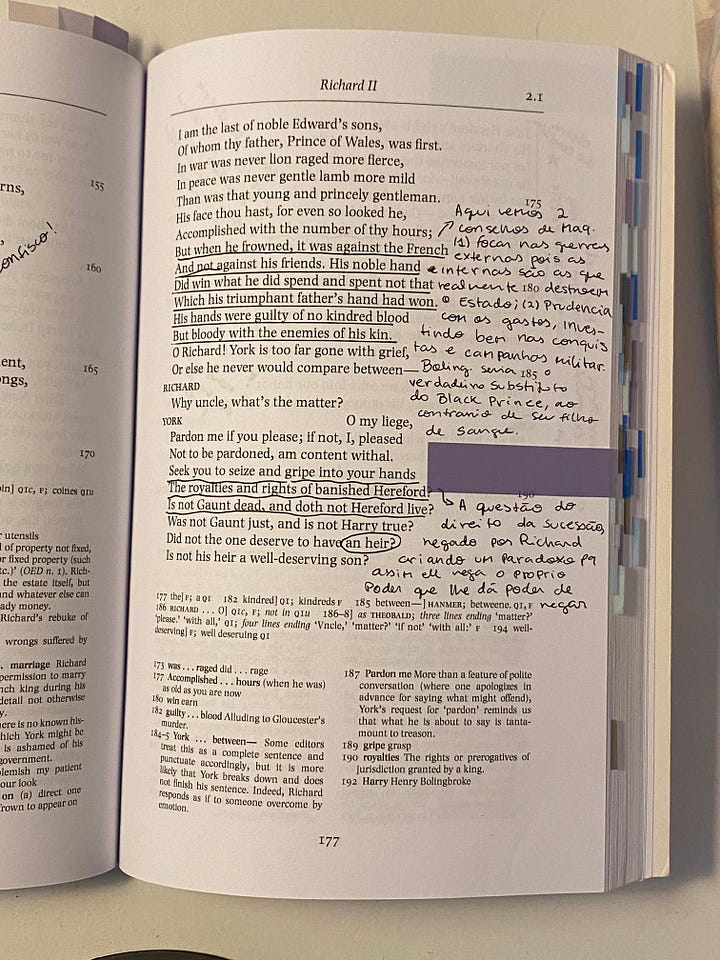

Paradise Lost and Richard II, respectively Try to interpret a scene according to your understanding (would the character say that shouting or whispering? why? and how does it change the meaning of the text?);

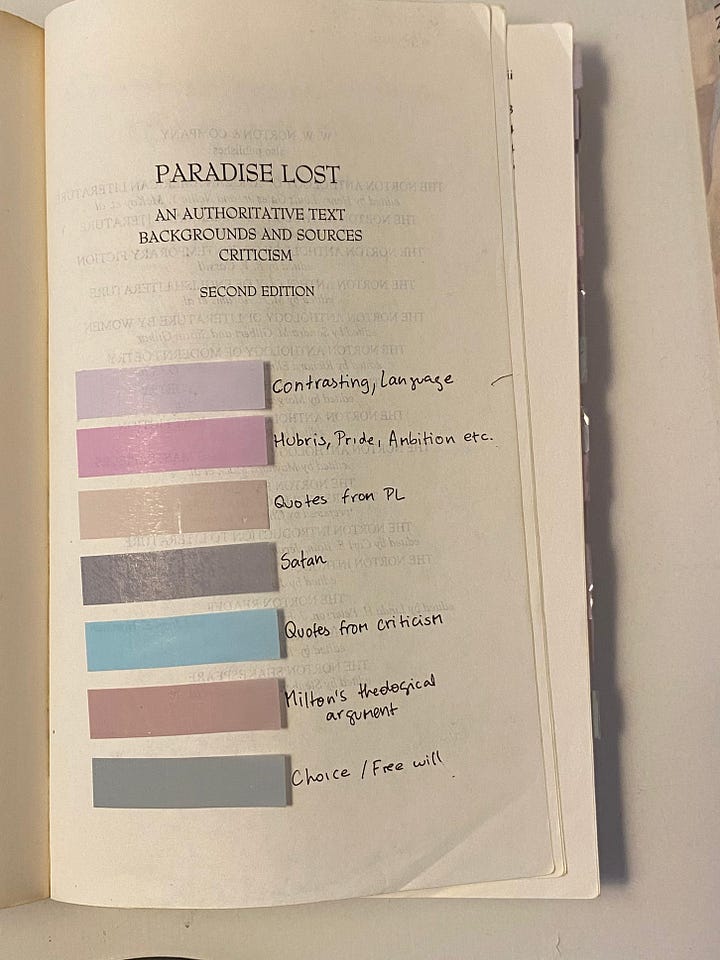

Identify themes and use colour tabs to identify them. ‘Ah, but what if I start reading and I don't know what themes I'm going to find in the play?’ Well, I always research the work I want to read in depth beforehand, and in these cases, I don't care much about spoilers. It's super simple, for example, I google ‘Hamlet themes’ and see which ones come up (usually on sites like the RSC's, or even SparkNotes), decide which ones interest me, and set up the annotation system (as in the photo below). This helped me a lot when writing my dissertation on Richard II.

Keep a reading journal: for those who are more traditional, you can dedicate a specific notebook to commenting on your readings; for those who are more technological, you can create a page on Notion. I've done it both ways and usually prefer Notion. You make notes as you see fit. I usually highlight interesting passages and write comments about them, or just write down ideas and impressions that the text has given me.

Read aloud: like poetry, Shakespeare's plays rely heavily on the sonority of the text. Sometimes a confusing scene becomes clearer after hearing the text. In Shakespeare's plays, there are no didascalia (instructions written by the author to guide the staging, indicating actions, gestures, emotions of the characters, scenery or sound and visual effects), so you need an extra dose of attention and imagination to understand the emotions that drive a particular scene.

...or listen to someone reading: nowadays, with my Audible subscription, I only read Shakespeare's plays by listening to the audiobook simultaneously ( it's what they call shadow reading) because as well as being an infinitely more immersive reading experience, listening to the intonation of the text is essential to help me interpret the play correctly.

I promise that none of this is frills or exaggeration, because certain works are worth the work they give us—the reward of a Shakespeare play is always the enchantment, and doing all this work teaches you to be a better reader. We can conclude that Shakespeare's plays are not closet dramas, namely, a play written to be read, not staged, whose focus is more on language and ideas than on theatrical performance. The performance in Shakespeare is just as important as the text, and keeping this in mind changes the way we read. I'll talk more about this later with recommendations for adaptations.

IV. Resources and Further Reading

With the crazy amount of information, choices and sources online, it’s hard to know where to begin or what to look for. This section is for those who want to study Shakespeare independently but don’t know where to find the necessary resources.

Websites:

Open Source Shakespeare

This is a Shakespeare database with all plays and sonnets, but the cool thing is that you can use this website to search for a word across all Shakespearean works. For example, the word ‘sleep’ occurs 270 times in 387 speeches within 42 plays. It appears the most in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, being mentioned 40 times, while the average in the other plays is 15. ‘Madness’ appears 18 times in Hamlet, compared to an average of 2 times in the other plays. This is extremely useful for researchers, I wish I had known about this website during college.

The Complete Works of Shakespeare Online

If you don’t want to buy a copy before being sure you will even like it, you can take a look at the plays on this website. All Shakespeare plays are there, well organised and divided by scenes.

JSTOR

This is my favourite website in the world. It’s my go-to source for studying and researching, since it’s a huge database for academic papers. You can search by keywords, and I promise you there is an article for every single aspect of every Shakespeare play in the world. With a free account, you can read 100 articles per month, create folders, and the site can even generate the references for you.

Internet Archive

One of the most important websites in the history of the internet and I will die on this hill. Internet Archive is an extremely important source for preserving internet history, besides having a huge archive of digitalized books that I often consult. I’ve read an entire book on T.S. Eliot’s Four Quartets and Helen Vendler’s The Odes of John Keats.

Academic Journals

All of these journals can be found on JSTOR :)

Shakespeare Quarterly

Shakespeare Quarterly is a peer-reviewed journal that publishes research on various aspects of Shakespeare studies. Its scope includes work on new media, early modern race, textual and theatre history, ecocriticism, posthumanism, psychoanalytic theory, and archival and historicist approaches. It is published by Oxford University Press for the Folger Shakespeare Library

Shakespeare Survey

Ran by Cambridge University, this publication “is a yearbook of Shakespeare studies and production. Since 1948 Survey has published the best international scholarship in English and many of its essays have become classics of Shakespeare criticism.”

Shakespeare Studies

This one is an annual peer-reviewed publication that showcases the work of Shakespearean scholars concerning performance, literary criticism, and cultural history. While centred on Shakespeare and his contemporaries, it also includes theoretical and historical research that explores broader cultural, political, and artistic contexts beyond early modern England. Boston University runs it.

Shakespeare Bulletin

Shakespeare Bulletin is a quarterly peer-reviewed journal focused on innovative research in Shakespearean and early modern performance and theatre history. It includes reviews of productions, films, and books, and is edited by an international team based at the University of Exeter's Centre for Early Modern Studies.

Renaissance Studies

A cross-disciplinary journal that features scholarly articles and document editions covering diverse facets of Renaissance history and culture. Its content spans the realms of European history, visual arts, architecture, religious studies, literature, and languages from the Renaissance era. It often includes articles on Shakespeare within a broader context.

Early Modern Literary Studies

It features research on English literature, language, and literary culture from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The journal also includes responses to published articles through its Readers' Forum, along with reviews of recent publications and scholarly tools relevant to early modern studies. Just as with the Renaissance Studies journal, it covers Shakespeare and Shakespeare-related themes within a broader context.

Books and Scholars

Jonathan Bate

My favourite Shakespeare scholar, who wrote Soul of the Age: A Biography of the Mind of William Shakespeare, The Genius of Shakespeare, and How the Classics Made Shakespeare. For historical and political context on Shakespeare’s time, read the excellent essay ‘Was Shakespeare an Essex Man?’.

A.C. Bradley

English author of Shakespearean Tragedy: Lectures on Hamlet, Othello, King Lear, and Macbeth (1904), which I still have to read, and the great Oxford Lectures on Poetry (1909), which I read about half of. He is a great reference to have in mind, especially since much of modern criticism was influenced by him (either agreeing or disagreeing).

Marjorie Garber

She is a Harvard professor who wrote the excellent Shakespeare After All (2004), which I used in my thesis. Based on thirty years of lecture courses at Yale and Harvard, Marjorie Garber presents analyses of Shakespeare’s plays in chronological order, from The Two Gentlemen of Verona to The Two Noble Kinsmen. The chapter on Richard II is truly excellent.

Franco Moretti

Wrote one of the best books of literary criticism I’ve ever read: Signs Taken for Wonders (1983). In it, there’s a chapter that inspired my whole thesis, ‘The Great Eclipse: Tragic form as Deconsecration of Soverignty’, in which he explains how Shakespeare’s depiction of a King’s deposition indicates the secularisation of kingship as a whole during the Early Modern period. It’s incredibly interesting to me, and I urge you to read it.

W.H. Auden

English poet, playwright, critic, and librettist who was published in 1930 for the first time, with the help of T.S. Eliot. In 1946, he gave a course on Shakespeare at the New School for Social Research, proposing to read all Shakespeare’s plays in chronological order, and this course was transformed into the book Lectures on Shakespeare by Arthur Kirsch.

Paul Cantor

He taught at the University of Virginia and was not just a brilliant scholar but also a wonderful lecturer. His classes are available on YouTube (I'll drop the links in the next section). He authored Shakespeare’s Roman Trilogy: The Twilight of the Ancient World (2017), which is still on my to-read list, and also wrote one of my go-to books on Romanticism, Creature and Creator: Myth-Making and English Romanticism (1984). It's a gem whenever I’m diving into that topic.

Katherine Duncan-Jones

An academic I deeply admire, she was Professor of English Literature at the University of Oxford from 1998 to 2001 and wrote Shakespeare: An Ungentle Life. You can find a few of her essays on JSTOR, such as ‘Playing Fields or Killing Fields: Shakespeare's Poems and "Sonnets"‘.

Harold Bloom

The most famous on the list and probably the most controversial. I have his book Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human on my shelf. Every time I finish a play, I go read a chapter on it. Bloom’s opinions are presented as absolute truth, so you have to be attentive not to fall for his rhetoric. I may agree with him on many things Shakespeare-wise, but I always have in mind that his statements are sometimes overstated opinions; he may not know it, but his word was not written in the 10 commandments.

Helen Vendler

Probably my idol and the kind of professor I’d like to be someday. As a poetry specialist, she has a book on the sonnets, not the plays. The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets is a book that is high on my TBR. Last year, I read her book on Keats’s Odes, and it was excellent. I’m sure this one is just as great.

J. Dover Wilson

He may be obsolete now, but his influence is a lasting one. I have partially read What Happens in Hamlet (and I intend to finish it this year), a curious book that argues for the importance of Hamlet’s ghost and the supernatural in the play. The next book I want to read by him is The Fortunes of Falstaff, an examination of one of the most interesting Shakespearean characters.

Samuel Taylor Coleridge

The great Romantic poet has a book of his teachings on Shakespeare, Lectures on Shakespeare. Coleridge is a foundational figure in Shakespeare criticism, and remains to this day one of the most incisive and best. You can find the book on Internet Archive.

Walter Pater

He is one of my favourite writers (you MUST read Studies in the History of the Renaissance), and in his book Appreciations with an Essay on Style (1889), you can find a great essay titled ‘Shakespeare’s English Kings’. Pater’s criticism is impressionistic, so it’s not the best source for regular academic research (unless you intentionally want to use his ‘impressions’), but it’s beautiful and thought-provoking. My thesis’s epigraph came from this essay: ‘The irony of kingship — average human nature, flung with a wonderful pathetic effect into the vortex of great events’. You can find it on Project Gutenberg.

Samuel Johnson

The first and most important Shakespeare critic, and an extremely important figure of the 18th century. Dr. Johnson's book Notes on Shakespeare is as canonical as the plays themselves. He is witty and sometimes extravagant; I love his prose, and if you want to know how Shakespeare used to be read almost 300 years ago, read him. You can also find it on Project Gutenberg.

The Cambridge Companions

Great anthologies of literary criticism. They are easy to find online and are very useful if you want to explore different themes in one play, all in the same place, from a trustworthy source. I recently used the Cambridge Companion to The Waste Land to study the poem, and it was extremely useful.

Philosophers on Shakespeare, ed. by Paul A. Kottman

This is a fascinating anthology of diverse philosophers and critics discussing Shakespeare in an interdisciplinary approach (which I love), from Hegel to Walter Benjamin, Nietzsche to Derrida, etc. It’s not an easy read, but super interesting. Go research the concept of Hegelian Tragedy, it’s one of my favourite literary-philosophical topics.

Lectures and Podcasts

Jonathan Bate’s lectures for Gresham College

In this playlist, you can find six lectures on Shakespeare given by Sir Jonathan Bate. He is one of the best professors I’ve ever seen. Click here to access.

Paul Cantor’s Lecture on Shakespeare and Politics

I used it for my thesis. These are truly great. You can watch it here.

Shakespeare Unlimited Podcast

A podcast by the Folger Shakespeare Library that features academics and contemporary authors talking about a wide range of aspects of Shakespeare's work. It’s the one I listen to the most.

Approaching Shakespeare Podcast

A podcast managed by Oxford University, ‘each lecture in this series focuses on a single play by Shakespeare, and employs a range of different approaches to try to understand a central critical question about it.’ You can find the episodes here.

Great Writers Inspire: Shakespeare Podcast

Similar to Approaching Shakespeare, this podcast proposes discussions with scholars about the plays. It’s more of a lecture than a debate. I usually take notes while listening to it. You can find the episodes here.

RSC Playing Shakespeare

For those interested in Shakespeare in performance, watch this documentary. I haven’t finished all the episodes yet, but it’s truly amazing to see. I love listening to actors talking about their craft. Here, John Barton holds a master class in how to play Shakespeare, using members of the Royal Shakespeare Company doing scenes, sonnets, and commentary as prime examples. Watch it here.

V. ‘The play is the thing’

Finally, every Shakespearean experience is only complete after watching an adaptation. There are hundreds of them, and I'm only going to recommend the ones I've seen, but remember to research beyond my suggestions!

Hamlet - Laurence Olivier (1948)

The best adaptation of Hamlet I've ever seen, truly worth its classic status. The aesthetic influenced by German expressionism blended perfectly with the sombre tone of the play, and Laurence is obviously a brilliant actor.

Hamlet - dir. by Robert Icke with Andrew Scott (2018)

I'm very partial to Andrew Scott, but he really is brilliant in this play. I personally prefer Hamlet to be more insane than brooding, and Scott's descent into madness is a joy to watch.

Hamlet - dir. Gregory Doran with David Tennant (2009)

David Tennant is one of my favourite actors, and his comic and ironic version of Hamlet brings a fresh interpretation to a mostly dark play. You can watch it in full here:

Much Ado About Nothing - dir. Kenneth Brannagh (1993)

I don't really like anything Brannagh does (that's why I haven't included his Hamlet here), but this marvellous adaptation is an exception. Emma Thompson is very good, and the film has a cottagecore aesthetic that is pleasant to watch.

Much Ado About Nothing - dir. by Josie Rourke with David Tennant (2011)

My favourite adaptation of my favourite comedy. I literally cried laughing with David as Benedick, and I really enjoyed the creative liberties taken by the director. Sadly they've removed the entire play from YouTube, but you can find it on sites like Stremio. In the meantime, watch this marvellous scene:

The Tragedy of Macbeth - dir. Joel Coen with Denzel Washington (2021)

A phenomenal adaptation, bleak in just the right measure, and with impeccable photography that references Olivier's Hamlet. I think it's hard to imagine anyone doing a better version of Macbeth. You can watch it on Apple TV, here's the trailer:

Romeo + Juliet - dir. Baz Luhrmann with Leonardo DiCaprio (1996)

Surely you've seen at least one scene from this film or some girl dressed up as Claire Danes' Juliet. It's a controversial adaptation, but I love it. Of course, it's not completely faithful to Shakespeare's idea, but if fidelity is to be sacrificed, let it be a fabulous sacrifice, which is the case with Luhrmann's work. You can watch it on Disney+.

Romeo and Juliet - Franco Zeffirelli (1968)

I remember watching this film as a teenager and being completely enchanted. The film is like a fairy tale, it's so beautiful. The performances aren't its strong point, but I love it all the same.

King Lear - dir. Richard Eyre with Anthony Hopkins (2018)

It's hard to find a good adaptation of King Lear, don't ask me why, but I imagine it's a really challenging play to stage. Although somewhat imperfect, I liked this version with Anthony Hopkins as King Lear (along with a great cast). Still, I'd like to see a version of King Lear in the style of Coen's Macbeth. Below, the famous scene of the division of the kingdom:

Othello - dir. Clint Dyer (National Theatre Live) (2023)

An excellent performance, unfortunately I can no longer find the full play on YouTube. But I'll put up the trailer to give you an idea:

The Hollow Crown - BBC TV series (2016)

This series is my favourite Shakespearean piece of media, and it is unbelievably good. Each episode is a play from the English Histories, starting with Richard II and ending with Richard III. So many great actors: Jeremy Irons as Henry IV, Tom Hiddleston as Henry V, Benedict Cumberbatch as Richard III, Patrick Stewart as John of Gaunt, Sally Hawkins as Queen Eleanor, Sophie Okonedo as Queen Margaret… honestly, it’s one of the best TV Shows I’ve ever watched. Here is my favourite scene from Henry IV Part 1, between Hal and Falstaff:

My Own Private Idaho - Gus Van Sant (1991)

For those who didn’t know, this movie is based on Henry IV — I had no idea until I was in the movie theatre, 30 minutes in, and I realised Keanu Reeves was doing Prince Hal’s monologue. This isn’t a faithful adaptation by any means, but it’s excellent in its creativity, proving how rich Shakespeare’s text can be and how much room for experimentation exists inside his plays. That’s the beauty of it. Here’s a scene equivalent to Hal’s rejection of Falstaff (I cried) (obviously is a minor spoiler):

10 Things I Hate About You - Gil Junger (1999)

Between the 90s and the early 2000s, teenage adaptations of classic literature were in vogue. The best one is, undoubtedly, 10 Things I Hate About You — my favourite teen movie by the way. This is way better than Zeffirelli’s adaptation of The Taming of the Shrew with Elizabeth Taylor, and I mean this unironically. Shakespeare would be proud to see Heath Ledger as Petruchio. I’m not joking when I say this stupid poem always makes me tear up a bit.

Rosencrantz & Guildenstern Are Dead - dir. Tom Stoppard (1990)

It's not exactly an adaptation of a Shakespeare play, but it's probably the greatest re-imagining of a Shakespeare play we have. The script is by Tom Stoppard, who also directed this amazing film about what Rosencrantz (Gary Oldman) and Guildenstern (Tim Roth) were doing during the course of Hamlet. It's hilarious and intelligent, watch it!

This is fantastic! As someone who is diving back in to a deep dive of Shakespeare (starting with my favorite Macbeth) this was such an informative piece! As someone who is looking to expand more into his other works, do you think its best to just start reading the plays, or to first research about them? There are some plays I know absolutely nothing about (Titus Andronicus) being one- and I’m so tempted to research it like crazy. But would that take away from the experience?

As a person who read all of his work and watched almost every piece of theatre and performance of his plays, I love this. 🤍 I will read your piece one more time in case I missed something.

On another note, I have a tiny recommendation on Romeo & Juliet; I know it is the most common read and play and I did grow tired of watching the different renditions after a while, however there is this one performance on National Theatre, they filmed it during the pandemic with Josh O’Connor as Romeo and it is by far the best R&J and the best Romeo I have ever watched.

I know it’s not your favourite but I say give it a try ☺️