Methought - July/2025

Monthly wrap-up: falling in love with James Joyce again, new favourite french films, rereading Jane Austen, the difficulty of defining literature, and how to resist the seductions of A.I.

Scroll down to read the English version

Caros leitores,

Julho foi um daqueles meses de leitura ideal, e eu estou feliz em anunciar que A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man tem potencial de ser um novo livro favorito (mas só o tempo vai dizer). Vi ótimos filmes franceses, e li um artigo alarmante sobre A.I. — quase me fez querer escrever sobre, mas já tem textos demais sobre isso no mundo, e eu não gosto de escrever sobre o que eu desprezo.

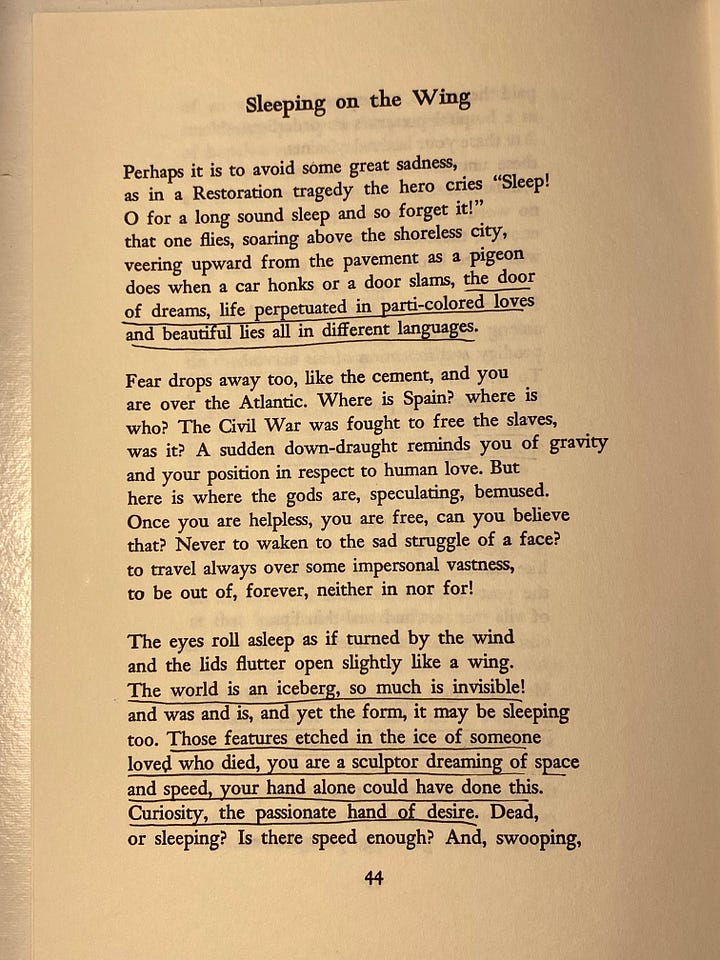

Pois bem, visto que li um livro de Frank O’Hara este mês, nada mais apropriado do que escolher um poema dele para compartilhar aqui:

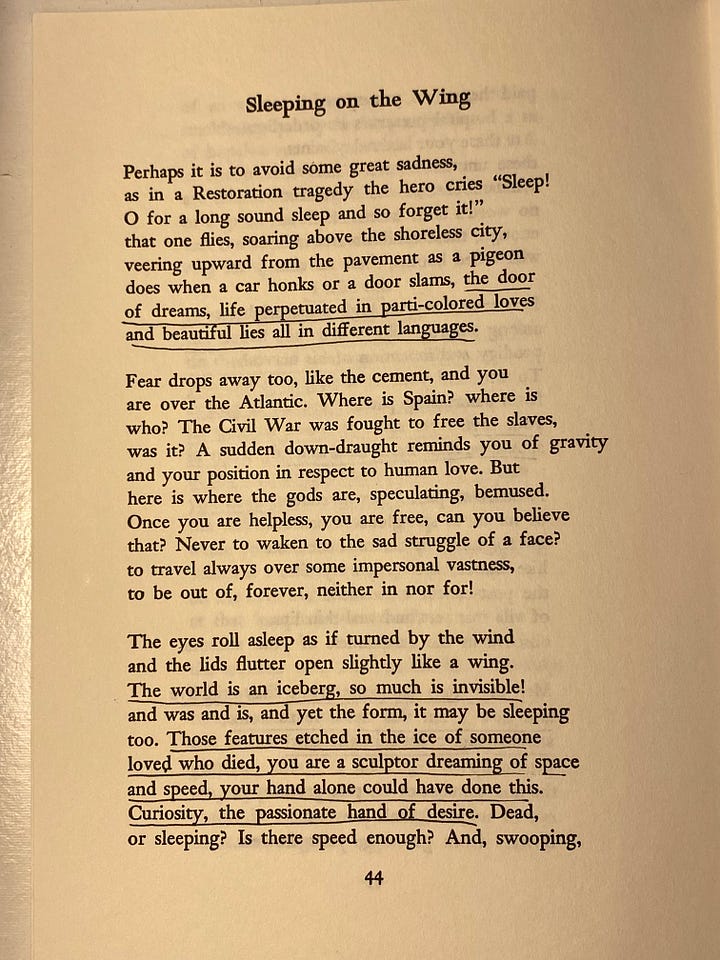

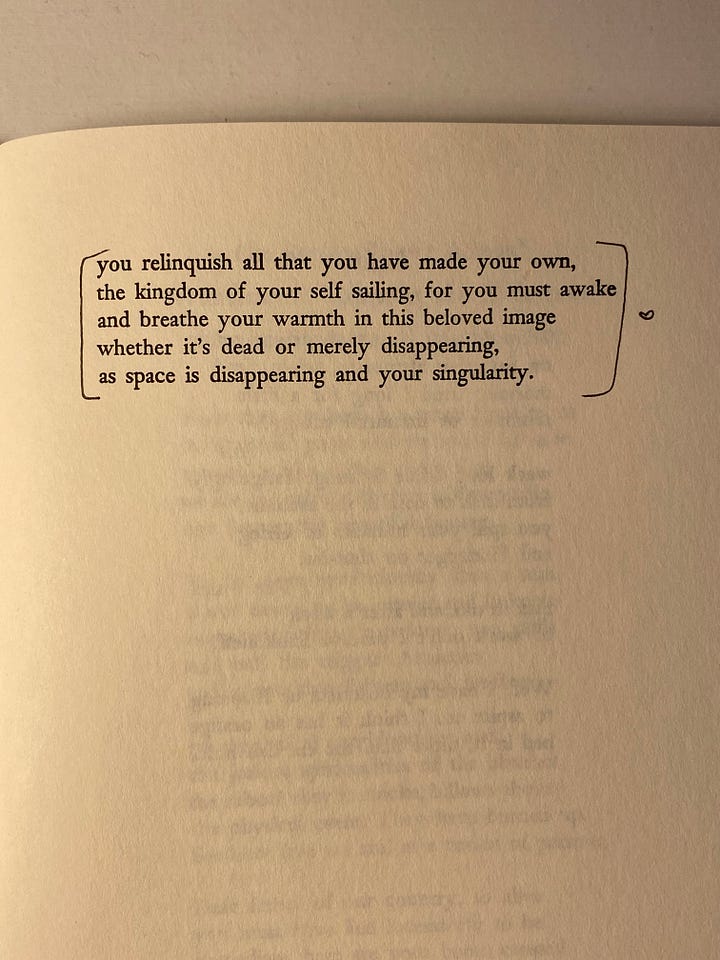

Sleeping on the Wing - Frank O’Hara

Este mês, iniciei uma nova série sobre meus livros favoritos, você pode conferir a parte 1 aqui:

Favourite Books from a Very Critical Person - part 1

In September, this newsletter will be three years old, and I realised that in all that time, I've never discussed one of the most beloved (and obvious) topics within the literary community, namely: my favourite books.

LIVROS &TC

King Lear - William Shakespeare (c. 1606)

“Uneasy lies the head that wears a crown”, disse Henrique IV em outra peça de Shakespeare, e King Lear começa com um monarca que parece compartilhar do sentimento, a ponto de abdicar (parcialmente) do trono e dividir seu reino entre três filhas. No entanto, o rei não pode dividir seus dois corpos e manter ambos: um rei tem um corpo político-simbólico e um corpo físico, através do qual ele incorpora o direito divino. Quando Lear decide fazer uma espécie de “renúncia suave”, ele involuntariamente inicia o processo de dessacralização de sua soberania, que será consolidado por meio de sua humilhação prolongada: ele começa a ser despojado dos símbolos de sua majestade e culmina com seu corpo sofrendo a destruição definitiva pelas mãos da Natureza.

Considero essa a peça mais desafiadora e trágica de Shakespeare, e continua sendo difícil de entender suas nuances mesmo numa releitura. Poderia passar anos estudando King Lear sem ter um momento de tédio.

A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man - James Joyce (1916)

A estrutura desta obra semi-autobiográfica baseia-se no crescimento de um menino sensível até à idade adulta, mas ao invés do tradicional Bildungsroman, A Portrait seria mais especificamente um Künstlerroman. As etapas do desenvolvimento de Stephen são construídas com foco no seu amadurecimento artístico, isto é, como as experiências de sua juventude moldaram a sua filosofia artística pessoal.

Cada uma das cinco partes do livro encerra um período da vida de Stephen com o que Joyce, num rascunho anterior, chamou de epifania: uma revelação peculiar da realidade interior de uma experiência. Segundo Wayne Booth (The Rethoric of Fiction): “Embora algumas das epifanias sejam cômicas, outras tristes e outras mistas, o efeito básico é sempre o mesmo: uma sensação avassaladora — quando elas são bem-sucedidas — do que Joyce gostava de chamar de “encarnação”: o significado artístico passou a ganhar corpo no mundo. O poeta fez seu trabalho”

Joyce mescla referências mitológicas (Ícaro e Dédalo), teológicas (a rebelião de Lúcifer), filosóficas (Aristóteles e Tomás de Aquino) e literárias (Byron e O Conde de Monte Cristo), refletindo a prática modernista de fundir o clássico e o novo, como defendeu T.S. Eliot em Tradition and the Individual Talent. Embora a obra de Joyce seja conhecida por seus desvios das convenções literárias, ele também era extremamente familiarizado com o cânone clássico, retrabalhando a tradição e criando algo inteiramente novo e não menos brilhante.

Persuasion - Jane Austen (1816)

Todo ano eu releio pelo menos um livro de Jane Austen por questões de saúde mental, isto é, ler os romances dela automaticamente melhora meu humor. A primeira vez que li Persuasion foi em 2022 e eu não sabia praticamente nada da história, o que foi ótimo pois é o livro mais misterioso de Austen na minha opinião. As verdadeiras intenções e o caráter de vários personagens ficam escondidas em meio a contradições e interpretações alheias, principalmente dos dois interesses românticos de Anne, nossa protagonista maravilhosa, o que contribui para uma narrativa bastante envolvente.

Diferentemente dos outros romances de Austen, a heroína de Persuasion não é uma jovenzinha recém saída da adolescência e que está descobrindo o mundo pela primeira vez. No começo da história, Anne é uma mulher de 27 anos que já se apaixonou e acabou tendo que abrir mão desse amor por circunstâncias alheias. Ela vive com um pai e uma irmã mais velha, ambos comicamente vaidosos e tolos (Austen tem um grande talento para criar pais divertidos). Por ser mais séria e introspectiva, Anne é constantemente ignorada e desmerecida pela família. Quando ela se vê livre da sombra deles pela primeira vez, ela tem a chance de ser apreciada por ser ela mesma em um novo circulo social, além de ter uma segunda chance para o amor.

É interessante ver Austen explorando os problemas da juventude tardia. Por mais que Anne tenha muito ainda para aprender, ela tem uma bagagem psicológica que usa como guia, e Austen costura esses dois aspectos para formar uma personagem muito convicente e de fácil identificação. Esse meio termo entre experiência e inocência, que resume essa fase da vida de Anne, é agrioce, e contribui para que Persuasion seja o livro mais “sério” da autora. Considerando essa direção que a escrita de Austen estava tomando, fico muito triste em pensar nos livros que poderíamos ter tido, se a autora não tivesse falecido tão jovem — Persuasion foi o último livro que ela completou.

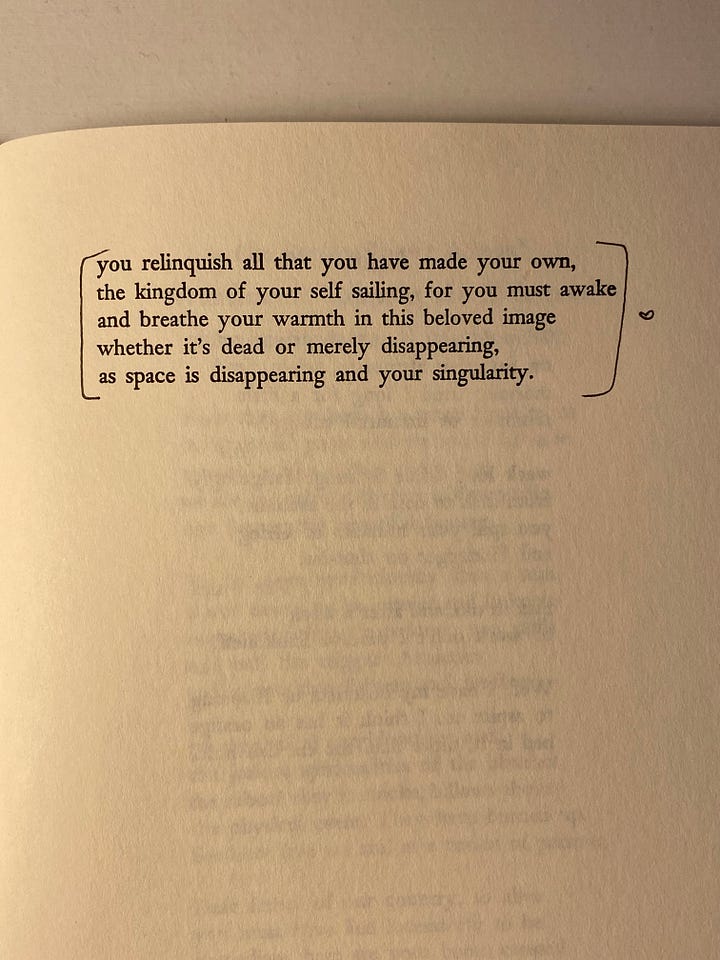

Meditations in an Emergency - Frank O’Hara (1957)

Como muitos dos poemas dessa coletânea, o título já sugere uma contradição: Como é possível meditar durante uma emergência? Como pode-se tomar a atitude mais deliberadamente passiva durante uma situação que requer ação imediata? Esse tipo de ironia é comum na poesia de Frank, tal como podemos ver em um de meus versos favoritos encontrados nesse livro: “I am the least difficult of men | All I want is boundless love.”

Tem algo mais difícil de encontrar do que um amor verdadeiramente sem limites? Queremos ser elegantemente comedidos durante o apocalipse, e queremos imaginar que o amor absoluto não é nada demais a se desejar – é simples na verdade. É claro que a realidade é outra, mas não custa nada imaginar essas perfeições absurdas, e nenhum meio é mais apropriado para expressar isso do que a poesia. Frank combina humor, romantismo e referências clássicas e vulgares, criando identificação entre leitor e eu líric mesmo quando estamos incertos do que ele realmente quer dizer.

Meus poemas favoritos desta coletânea foram: To the Harbormaster; “There I could never be a boy”; The Hunter; For Grace, After a Party; Two Variations; Ode; Meditations in an Emergency; Sleeping on the Wing.

ARTIGOS, ENSAIOS, PALESTRAS

The Seductions of A.I. for the Writer’s Mind - Meghan O’Rourke para o New York Times

For now, many of us still approach A.I. as outsiders — nonnative users, shaped by analog habits, capable of seeing the difference between now and then. But the generation growing up with A.I. will learn to think and write in its shadow. For them, the chatbot won’t be a tool to discover — as Netscape was for me — but part of the operating system itself. And that shift, from novelty to norm, is the profound transformation we’re only beginning to grapple with.

Uma professora de poesia de Yale decide escrever um texto sobre o uso de Inteligência Artificial — principalmente na sala de aula, onde ela está cansada de ver estudantes se apoiando cada vez mais nessas ferramenta — usando a si mesma como cobaia. Ela se apresenta ao Chat GPT (que a reconhece, pois aparentemente ele já “leu” e “ensinou” muito da obra dela) e começa a pedir ajuda para pequenas coisas, como elaboração de emails e planejamento de rotina.

Porém, ela não esperava que este experimento iria deixá-la viciada em usar A.I. para tudo, e a epifania veio quando ela percebeu a técnica de sedução do robô: você pede a ele uma coisa pequena e simples, como transformar um plano de aula escrito às pressas em um texto organizado em bullet points, e após entregar, ele sugere “requintes” de complexidade gradual; à certa altura, a A.I. estava pergutando se a professora gostaria que ele fizesse o plano de aulas do semestre inteiro, com uma lista de leitura elaborada por ele a partir do que ela tinha em mente. Você pede uma mão para o robô e ele está mais que pronto para oferecer um braço e uma perna, pois é assim que ele foi programado.

A partir disso, a professora reflete sobre a própria experiência usando A.I., bem como a de colegas e alunos, e sobre como esta tecnologia consegue tomar conta dos afazeres humanos sorrateiramente. Mas nem tudo está perdido.

In Praise of Jane Austen’s Least Beloved Novel - Adelle Waldman para o The New Yorker

“Northanger” ’s pleasures come not from the novel’s traditional method of inhabiting the mind of a character but from something more removed. Instead of causing us to become Catherine, Austen engages us in a conversation about Catherine. Since Austen’s observations are dry and ironic and sensible and compelling, this makes for very pleasant conversation, but it still leads to a more cerebral reading experience than we are accustomed to when we read fiction, particularly Austen’s fiction. Thus, the very quality that makes “Northanger” catnip for academics—its eloquence on the topic of “the Novel”—also makes it less of a novel qua novel than Austen’s other books.

Como o título sugere, este ensaio investiga a possível razão de Northanger Abbey ser preterido em comparação aos outros romances da Jane Austen e tenta demonstrar que tal razão (qual seja, uma forma narrativa que distancia o leitor da protagonista, e que requer uma boa percepção da ironia para ser devidamente apreciada), na verdade é uma dos aspectos mais interessantes do livro. Eu adorei Northanger Abbey — inclusive acho o livro mais engraçado de Austen — e fiquei surpresa ao saber que esta é a obra mais desprestigiada da autora; eu jurava que seria Mansfield Park. Catherine, a protagonista, é uma tola divertidíssima, e acho que o segredo para apreciar tanta tolice é não levá-la tão a sério. Se o leitor perceber que a própria autora convida o leitor a rir de Catherine (mas com carinho) como é sugerido neste ensaio, acho que é possível gostar mais da protagonista.

What is Literature? - Arthur Krystal para a Harper’s Magazine

“Literary” does not refer to “what is expressed, what is invented, in whatever form”, and literature does not encompass every book that comes down the pike, however smart or well-made. At the risk of waxing metaphysical, one might argue that literature, like any artifact, has both a Platonic form and an Aristotelian concreteness.

Como definir quais livros são “literatura” e quais não são (e porquê), ou pior ainda: como dar uma definição ampla o suficiente para abarcar a imensidão que é literatura, mas sem ser abrangente demais a ponto de qualquer coisa poder ser considerada literatura, fazendo com que a classificação em si perca o sentido? Esses são os principais problemas abordados no texto, e de antemão aviso que não há uma resposta concreta pois tal resposta é impossível.

É cada vez mais difícil encontrar uma forma de delimitar o que é literatura (como um valor) sem soar excludente e elitista; afinal, este tipo de classificação, por natureza, sempre poderá ser questionado. É necessário que haja algum rigor nesta classificação (que consequentemente cria a distinção, a vontade de pertencer à literatura) mesmo que haja o risco de acusações de arbitrariedade. É uma discussão polêmica, mas gostei de como o autor explica a importância do cânone não como um preceito que deve ser seguido, mas sim como um molde do qual o escritor do presente necessariamente é fruto. Portanto, tanto para leitores quanto para escritores, conhecer e apreciar a tradição literária nada mais é do que uma forma de enriquecer a experiência de criar e apreciar livros.

FILMES & SÉRIES

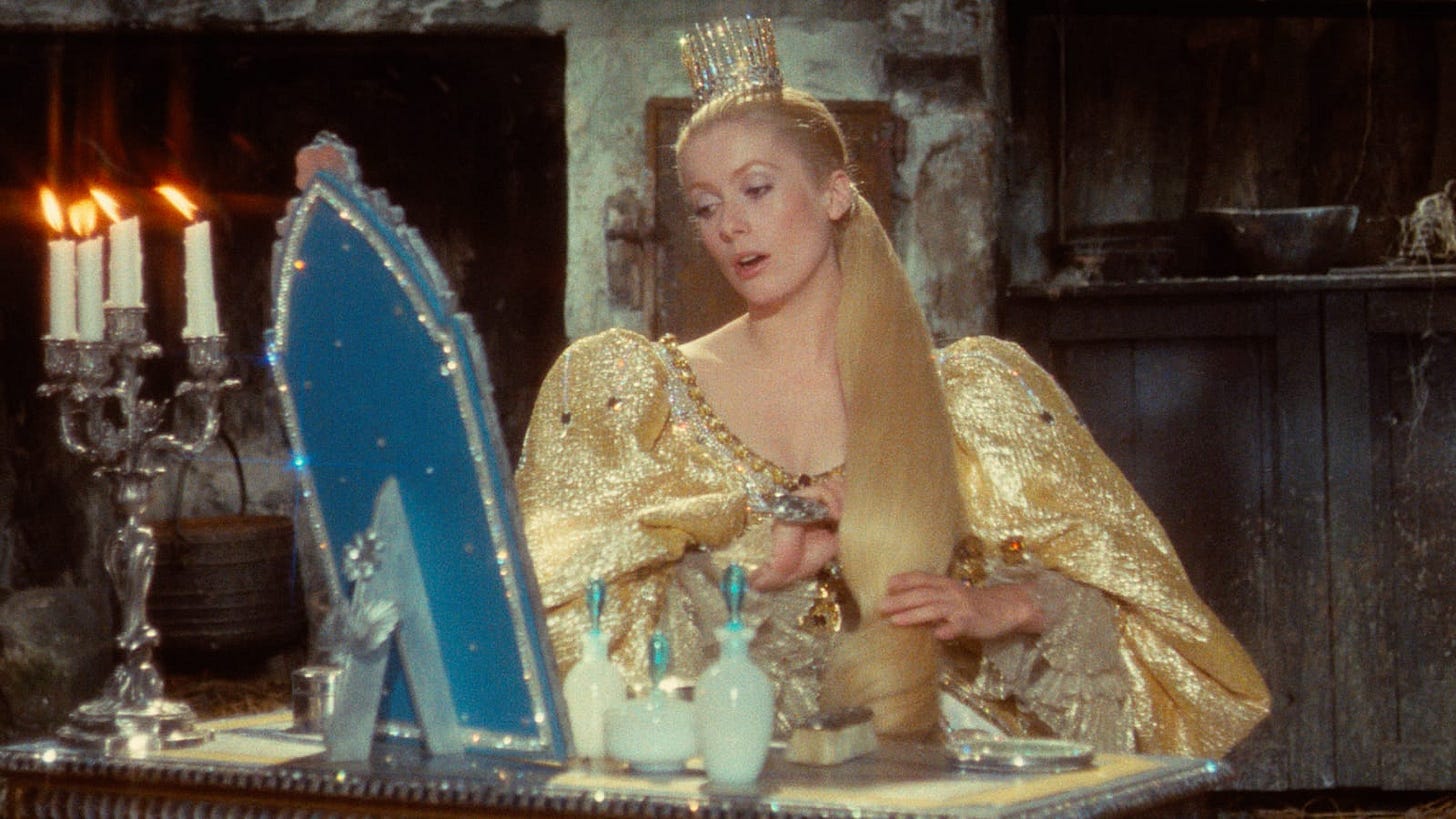

Peau D’âne - Jacques Demy (1970)

Uma das definições de uma obra pós-moderna é “uma obra consciênte de seu meio do gênero a qual pertence”. Isso pode ser feito de uma forma chata e meramente reprodutiva, ou pode ser muito interessante: Peau D’âne é um filme que não apenas sabe que é um filme, mas que é um filme de contos de fadas, e com isso consegue ser divertidíssimo e único, inteligente mas sem se levar a sério demais. Aqui Demy adapta uma história clássica de Charles Perrault sobre uma princesa que, para não ser obrigada a casar com o próprio pai, se disfarça usando uma pele de asno. Além de ser uma ótima história, contando com a maravilhosa Catharine Deneuve, é um dos filmes mais coloridos que já vi (que enorme satisfação ver cores num filme): a fotografia é linda e vibrante, figurinos fabulosos e cenários intencionalmente kitsch. Dá pra ver que Demy se divertiu fazendo esse filme, acho que os cineastas de hoje em dia deviam se inspirar nisso.

Phoenix - Christian Petzold (2014)

Às vezes eu me deparo com obras que, “objetivamente” eu considero boas, mas que ainda assim desgosto. Não sei se cheguei a desgostar de Phoenix, primeiro filme que vejo de Petzold, mas posso dizer que ele me irritou em vários momentos, principalmente devido à escolhas de atuação da atriz principal (Nina Hoss). A história sobre uma mulher vítima dos campos de concentração que passa por uma cirurgia de reconstrução de rosto, a ponto de ficar irreconhecível, e termina se passando por ela mesma fruto do plano de um marido duvidoso, tem muito potencial em tese, mas que achei que não foi explorado o suficiente. A sinopse aponta para questões de identidade, mas eu queria que isso tivesse sido mais discutido ou representado com mais desdobramentos. Ainda assim, esse filme tem um dos melhores finais que vi nos últimos tempos.

Shadow of a Doubt - Alfred Hitchcock (1943)

Dando continuidade ao projeto mais lento do mundo de assistir todos os filmes dirigidos por Hitchcock, esse mês eu assisti Shadow of a Doubt, um filme que logo de cara introduz uma relação esquisitíssima entre um tio e uma sobrinha, ambos chamados Charlie. Uncle Charlie é uma figura meio vampiresca, que foge de Nova York por algum envolvimento obsucro e desconhecido em direção à casa de sua irmã, numa cidadezinha na Califórnia. Lá ele é admirado como um homem de negócios, mas demora pouco para detetives chegarem na cidade e sua sobrinha começar a desconfiar dele. É divertido, principalmente por causa dos ótimos coadjuvantes, mas é apenas mais um thriller. Achei o final muito frustrante.

The Wind that Shakes the Barley - Ken Loach (2006)

Inspirado na minha leitura de A Portrait of the Artist, decidi assistir alguns filmes que tivesses a ver com o livro, e este foi um deles — uma ótima escolha pois The Wind that Shakes the Barley fala sobre a luta pela independência da Irlanda no começo do século XX, além de ser um dos filmes mais tristes que já vi, o que refrescou a minha raiva do império britânico, me deixando no humor certo para entender as críticas políticas feitas por Joyce.

Cillian Murphy interpreta um revolucionário nos primórdios do IRA, e depois vemos como essa organização se dividiu, desembocando na guerra civil irlandesa que duraria décadas. Infelizmente esse filme é bem atual, pois ele ilustra bem o caos social e emocional gerado pela guerra, e como mesmo chegando num ponto onde não se sabe mais o que está sendo defendido, é impossível se desvencilhar desse tipo de violência, já que ela acaba ganhando vida própria. Os “Black and Tans”, uma espécie de polícia britânica que aterrorizava os irlândeses, me lembraram muito das cenas que circularam a internet entre o ICE e os imigrantes nos EUA.

How to Steal a Million - William Wyler (1966)

Que filme DIVERTIDO. Eu sou uma grande fã de Audrey Hepburn (likely eu sei), como atriz e pessoa, e não sei como eu não tinha assistido essa incrível comédia romântica antes. Audrey interpreta Nicole, uma parisiense filha de um grande falsificador de arte, que inclusive adquiriu uma fortuna vendendo Cezannes e Van Goghs que ele mesmo pintou. Para impedir que a fraude de seu pai seja descoberta, ela precisa roubar uma de suas obras que está exposta num museu, com a ajuda do misterioso e suave Dermott (Peter O’Toolee). Destaque para o figurino Givenchy magnífico.

The Sting - George Roy Hill (1973)

Adoro quando filmes me enganam, e eu me senti uma criança assistindo The Sting — uma reação muito apropriada visto que este filme é justamente sobre falcatruas, golpes, mentiras, e enganações. Não suspeitei de nada e toda pequena reviravolta me surpreendeu. Adorei ver Paul Newman e Robert Redford (o midcentury Brad Pitt) como parceiros golpistas. Se você gosta de Ocean’s Eleven, assista esse filme pois ele é the blueprint.

Cloud - Kiyoshi Kurosawa (2024)

Este é um filme bem esquisito, que começa devagar, como um thriller lento com toques de horror, e termina quase como uma fábula moral sobre a desumanização que pode ocorrer através da cultura digital. Balanceando o cômico e o incômodo, Cloud é uma obra que pode confundir muita gente com relação à sua proposta: é uma sátira do gênero? é uma denúncia social? é um suspense inspirado em obras ocidentais como Black Mirror? Pode ser todas elas em parte. Ou nenhuma e fui eu que não entendi nada. O que quer que seja, é um filme intrigante, mas não me importei o suficiente para querer estar certa sobre ele.

Léon Morin, prêtre - Jean-Pierre Melville (1961)

Me surpreendi muito com este filme, pois não esperava gostar tanto. A história se passa durante a República de Vichy na França. Barny (Emmanuelle Riva) é uma jovem inteligente e bastante progressista para a época: marxista, atéia, mãe solo e bissexual (apesar de não ter esta nomenclatura no filme). Movida por uma curiosidade mórbida e uma certa soberba intelectual, ela vai ao confessionário, mas ao invés de oferecer uma confissão para o padre, ela resolve questioná-lo teologicamente. Para a surpresa dela, o Padre Morin (Jean-Paul Belmondo) se revela um adversário intelectual à altura. A partir desse encontro, eles desenvolvem uma amizade baseada em conversas e leituras filosóficas e teológicas.

Não posso dizer qual foi o resultado desse relacionamento, mas tem muito em comum com Fleabag. A atuação dos protagonistas é maravilhosa, e o texto do filme é fantástico (principalmente considerando que boa parte do filme se resume à conversas). Em resumo: amei Léon Morin, com certeza será um dos favoritos de 2025.

MÚSICA & PODCASTS

A Little Touch of Schmilsson in the Night - Harry Nilsson (1973)

Esse álbum me traz uma paz imensa. Ouvi bastante esse mês enquanto estava escrevendo ou caminhando na rua. São covers de jazz no estilo folk de Harry Nilsson, que eu amo. Para quem não o conhece, ele tem uma vibe meio Nick Drake, Donovan, Cat Stevens, Graham Nash etc. O cover de “It Had to be You” é meu favorito, até porque é uma das minhas músicas favoritas.

It Appears that Children were Left Behind - Bitchtopia Podcast

Uma discussão igualmente importante e deprimente sobre o atual estado da relação que as crianças e adolescentes têm com a literatura. Baseado em depoimentos de educadores e pesquisa extensa, as meninas do Bitchtopia conseguiram me deixar bastante alarmada — nada que eu já não soubesse, mas é pior quando se descobre dados concretos. Outra coisa: o sistema de educação dos Estados Unidos é uma das coisas mais pavorosas e absurdas que eu já vi. Explica muita coisa, infelizmente. Recomendo particularmente para você tem ou pretende ter filhos (ou trabalha educando crianças) e quer criá-los como seres funcionais.

Siboney - Playlist

Não lembro como encontrei essa playlist no Spotify, mas estive obcecada por ela. Particularmente boa para ouvir enquanto se cozinha. Segundo o criador da playlist, ela é “something beyond lynchian and not quite americana”. Whatever that means!

Dear readers,

July was one of those ideal months for reading, and I am happy to announce that A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man has the potential to be a new favourite book (but only time will tell). I watched some great French films and read an alarming article about A.I. — it almost made me want to write about it, but there are already too many texts on this subject in the world, and I don't like to write about what I despise.

Well, since I read a book by Frank O'Hara this month, nothing could be more appropriate than choosing one of his poems to share here:

Sleeping on the Wing - Frank O'Hara

This month, I started a new series about my favourite books. You can check out part 1 here:

Favourite Books from a Very Critical Person - part 1

In September, this newsletter will be three years old, and I realised that in all that time, I've never discussed one of the most beloved (and obvious) topics within the literary community, namely: my favourite books.

BOOKS &TC

King Lear - William Shakespeare (c. 1606)

“Uneasy lies the head that wears a crown,” said Henry IV in another Shakespeare play, and King Lear begins with a monarch who seems to share that sentiment, to the point of (partially) abdicating the throne and dividing his kingdom among his three daughters. However, the king cannot divide his two bodies and keep both: a king has a political-symbolic body and a physical body, through which he embodies divine right. When Lear decides to make a kind of ‘soft resignation,’ he unwittingly begins the process of deconsecrating his sovereignty, which will be consolidated through his prolonged humiliation: he begins to be stripped of the symbols of his majesty and culminates with his body suffering ultimate destruction at the hands of Nature.

I consider this to be Shakespeare's most challenging and tragic play, and it remains difficult to understand its nuances even upon rereading. I could spend years studying King Lear without ever getting bored.

A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man - James Joyce (1916)

The structure of this semi-autobiographical work is based on the growth of a sensitive boy into adulthood, but unlike the traditional Bildungsroman, A Portrait would be more specifically a Künstlerroman. The stages of Stephen's development are constructed with a focus on his artistic maturity, that is, how the experiences of his youth shaped his personal artistic philosophy.

Each of the five parts of the book closes a period of Stephen's life with what Joyce, in an earlier draft, called an epiphany: a peculiar revelation of the inner reality of an experience. According to Wayne Booth (The Rhetoric of Fiction): ‘Although some of the epiphanies are comic, others sad, and others mixed, the basic effect is always the same: an overwhelming sense — when they are successful — of what Joyce liked to call “incarnation”: artistic meaning has taken flesh in the world. The poet has done his work.’

Joyce mixes mythological (Icarus and Daedalus), theological (Lucifer's rebellion), philosophical (Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas) and literary (Byron and The Count of Monte Cristo) references, reflecting the modernist practice of merging the classic and the new, as advocated by T.S. Eliot in Tradition and the Individual Talent. Although Joyce's work is known for its deviations from literary conventions, he was also extremely familiar with the classical canon, reworking tradition and creating something entirely new and no less brilliant.

Persuasion - Jane Austen (1816)

Every year I reread at least one Jane Austen book for the sake of my mental health, that is, reading her novels automatically improves my mood. The first time I read Persuasion was in 2022 and I knew next to nothing about the story, which was great because it is Austen's most mysterious book in my opinion. The true intentions and characters of several characters are hidden amid contradictions and interpretations by others, especially Anne's two romantic interests, which contributes to a very engaging narrative.

Unlike Austen's other novels, the heroine of Persuasion is not a young girl just out of her teens and discovering the world for the first time. At the beginning of the story, Anne is a 27-year-old woman who has already fallen in love and ended up having to give up that love due to circumstances beyond her control. She lives with her father and older sister, both of whom are comically vain and foolish (Austen has a great talent for creating entertaining parents). Because she is more serious and introspective, Anne is constantly ignored and belittled by her family. When she finds herself free from their shadow for the first time, she has the chance to be appreciated for being herself in a new social circle, as well as having a second chance at love.

It is interesting to see Austen exploring the problems of late youth. As much as Anne still has a lot to learn, she has psychological baggage that she uses as a guide, and Austen weaves these two aspects together to form a very convincing and relatable character. This middle ground between experience and innocence, which sums up this phase of Anne's life, is bittersweet and contributes to Persuasion being the author's most ‘serious’ book. Considering the direction Austen's writing was taking, I am very sad to think of the books we could have had if the author had not died so young — Persuasion was the last book she completed.

Meditations in an Emergency - Frank O’Hara (1957)

As with many of the poems in this collection, the title suggests a contradiction: How is it possible to meditate during an emergency? How can one take the most deliberately passive stance during a situation that requires immediate action? This kind of irony is common in Frank's poetry, as we can see in one of my favourite verses from this book: ‘I am the least difficult of men | All I want is boundless love.’

Is there anything more difficult to find than truly unlimited love? We want to be elegantly composed during the apocalypse, and we want to imagine that absolute love is not too much to wish for — it is simple, really. Of course, the reality is different, but there is no harm in imagining these absurd perfections, and no medium is more appropriate for expressing this than poetry. Frank combines humour, romanticism and classical and vulgar references, allowing the reader to identify with the speaker even when we are unsure of what he really means.

My favourite poems from this collection were: To the Harbormaster; “There I could never be a boy”; The Hunter; For Grace, After a Party; Two Variations; Ode; Meditations in an Emergency; Sleeping on the Wing.

ARTICLES, ESSAYS, LECTURES

The Seductions of A.I. for the Writer’s Mind - Meghan O’Rourke for The New York Times

For now, many of us still approach A.I. as outsiders — nonnative users, shaped by analog habits, capable of seeing the difference between now and then. But the generation growing up with A.I. will learn to think and write in its shadow. For them, the chatbot won’t be a tool to discover — as Netscape was for me — but part of the operating system itself. And that shift, from novelty to norm, is the profound transformation we’re only beginning to grapple with.

A poetry professor at Yale decides to write a piece on the use of Artificial Intelligence — particularly in the classroom, where she is tired of seeing students increasingly relying on these tools — using herself as a guinea pig. She introduces herself to Chat GPT (which recognises her, as it has apparently already “read” and “taught” much of her work) and begins to ask for help with small things, such as writing emails and planning her routine.

However, she did not expect that this experiment would leave her addicted to using A.I. for everything, and the epiphany came when she realised the robot's seduction technique: you ask it for something small and simple, such as turning a hastily written teaching programme into an organised text with bullet points, and after delivering it, it suggests ‘refinements’ of gradual complexity; at a certain point, the A.I. was asking if the teacher would like it to do the whole semester's lesson plans, with a reading list drawn up by it based on what she had in mind. You ask the robot for a hand, and it is more than ready to offer an arm and a leg, because that is how it was programmed.

From this, the professor reflects on her own experience using AI, as well as that of colleagues and students, and how this technology manages to take over human tasks insidiously. Yet all is not lost.

In Praise of Jane Austen’s Least Beloved Novel - Adelle Waldman for The New Yorker

“Northanger” ’s pleasures come not from the novel’s traditional method of inhabiting the mind of a character but from something more removed. Instead of causing us to become Catherine, Austen engages us in a conversation about Catherine. Since Austen’s observations are dry and ironic and sensible and compelling, this makes for very pleasant conversation, but it still leads to a more cerebral reading experience than we are accustomed to when we read fiction, particularly Austen’s fiction. Thus, the very quality that makes “Northanger” catnip for academics—its eloquence on the topic of “the Novel”—also makes it less of a novel qua novel than Austen’s other books.

As the title suggests, this essay investigates the possible reason why Northanger Abbey is overlooked in comparison to Jane Austen's other novels and attempts to demonstrate that this reason (namely, a narrative style that distances the reader from the protagonist and requires a keen sense of irony to be properly appreciated) is actually one of the most interesting aspects of the book. I loved Northanger Abbey — I even think it's Austen's funniest book — and I was surprised to learn that it is the author's most underrated work; I would have sworn it was Mansfield Park. Catherine, the protagonist, is a hilarious fool, and I think the secret to appreciating such foolishness is not to take her too seriously. If the reader realises that the author herself invites the reader to laugh at Catherine (but affectionately), as suggested in this essay, I think it is possible to like the protagonist more.

What is Literature? - Arthur Krystal for Harper’s Magazine

“Literary” does not refer to “what is expressed, what is invented, in whatever form”, and literature does not encompass every book that comes down the pike, however smart or well-made. At the risk of waxing metaphysical, one might argue that literature, like any artifact, has both a Platonic form and an Aristotelian concreteness.

How to define which books are ‘literature’ and which are not (and why), or worse still: how to give a definition broad enough to encompass the immensity that is literature, but without being so comprehensive that anything can be considered literature, causing the classification itself to lose its meaning? These are the main issues addressed in the essay, and I warn you in advance that there is no concrete answer because such an answer is impossible.

It is increasingly difficult to find a way to define what literature is (as a value/concept) without sounding exclusionary and elitist; after all, this type of classification, by its very nature, can always be questioned. There needs to be some rigour in this classification (which consequently creates the distinction, the desire to belong to literature) even if there is a risk of accusations of arbitrariness. It is a controversial discussion, but I liked how the author explains the importance of the canon not as a precept that must be followed, but as a mould from which the writer of the present is necessarily the product. Therefore, for both readers and writers, knowing and appreciating literary tradition is nothing more than a way to enrich the experience of creating and enjoying books.

FILMS & SERIES

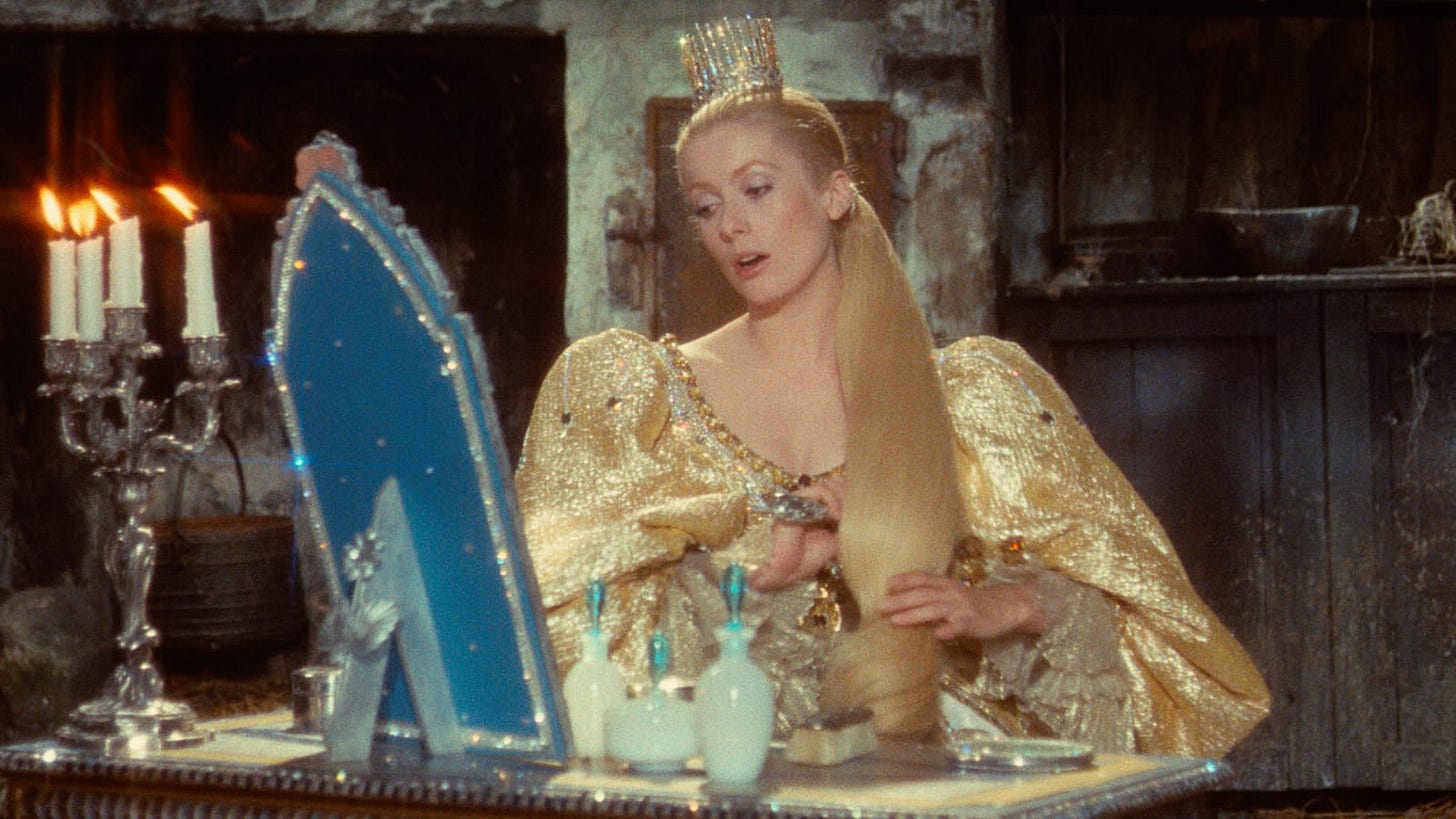

Peau D’âne - Jacques Demy (1970)

One definition of a postmodern work is “a work conscious of its genre and the medium to which it belongs”. This can be done in a boring and merely derivative way, or it can be very interesting: Peau D'âne is a film that not only knows it is a film, but that it is a fairy tale film, and with that it manages to be hilarious and unique, intelligent but without taking itself too seriously. Here Demy adapts a classic story by Charles Perrault about a princess who, in order to avoid being forced to marry her own father, disguises herself using a donkey skin. In addition to being a great story, featuring the wonderful Catherine Deneuve, it is one of the most colourful films I have ever seen (what a joy to see colours in a film): the photography is beautiful and vibrant, the costumes fabulous and the sets intentionally kitsch. You can see that Demy had fun making this film, and I think today's filmmakers should take inspiration from that.

Phoenix - Christian Petzold (2014)

Sometimes I come across works that I ‘objectively’ consider good, but still dislike. I don't know if I actually disliked Phoenix, the first film I've seen by Petzold, but I can say that it annoyed me at various points, mainly due to the acting choices of the lead actress (Nina Hoss). The story about a woman who was a victim of concentration camps and undergoes facial reconstruction surgery to the point of becoming unrecognisable, and ends up impersonating herself as part of her dubious husband's plan, has a lot of potential in theory, but I felt that it wasn't fully explored. The synopsis points to issues of identity, but I wanted this to have been discussed more or represented with more developments. Still, this film has one of the best endings I've seen in recent times.

Shadow of a Doubt - Alfred Hitchcock (1943)

Continuing with the world's slowest project of watching all the films directed by Hitchcock, this month I watched Shadow of a Doubt, a film that immediately introduces a very strange relationship between an uncle and his niece, both named Charlie. Uncle Charlie is a somewhat vampire-like figure who flees New York due to some obscure and unknown involvement and heads to his sister's house in a small town in California. There, he is admired as a businessman, but it doesn't take long for detectives to arrive in town and for his niece to begin to suspect him. It's entertaining, mainly because of the great supporting cast, but it's just another thriller. I thought the ending was very frustrating.

The Wind that Shakes the Barley - Ken Loach (2006)

Inspired by my reading of A Portrait of the Artist, I decided to watch some films related to the book, and this was one of them — a great choice, as The Wind that Shakes the Barley is about the struggle for Irish independence in the early 20th century, as well as being one of the saddest films I have ever seen, which refreshed my anger towards the British Empire, putting me in the right mood to understand Joyce's political criticism.

Cillian Murphy plays a revolutionary in the early days of the IRA, and we then see how this organisation split, leading to the Irish civil war that would last for decades. Unfortunately, this film is still relevant today, as it illustrates the social and emotional chaos generated by war, and how, even when you reach a point where you no longer know what you are defending, it is impossible to escape this type of violence, as it ends up taking on a life of its own. The ‘Black and Tans,’ a kind of British police force that terrorised the Irish, reminded me a lot of the scenes that circulated on the internet between ICE and immigrants in the US.

How to Steal a Million - William Wyler (1966)

What an FUN movie. I am a huge fan of Audrey Hepburn (likely, I know), as an actress and as a person, and I don't know how I hadn't seen this incredible romantic comedy before. Audrey plays Nicole, a Parisian girl whose father is a great art forger: he has made a fortune selling Cezannes and Van Goghs that he painted himself. To prevent her father's fraud from being discovered, she must steal one of his works that is on display in a museum, with the help of the mysterious and suave Dermott (Peter O'Toole). The magnificent Givenchy costumes are a standout feature.

The Sting - George Roy Hill (1973)

I love it when films fool me, and I felt like a child watching The Sting — a very appropriate reaction, given that this film is precisely about scams, con artists, lies, and deception. I didn't suspect a thing, and every little twist surprised me. I loved seeing Paul Newman and Robert Redford (the mid-century Brad Pitt) as con artist partners. If you like Ocean’s Eleven, watch this film because it’s the blueprint.

Cloud - Kiyoshi Kurosawa (2024)

This is a very strange film, which starts slowly, like a slow-paced thriller with hints of horror, and ends almost like a moral fable about the dehumanisation that can occur through digital culture. Balancing the comical and the uncomfortable, Cloud is a work that may confuse many people regarding its purpose: is it a satire of the genre? Is it a social critique? Is it a thriller inspired by Western works such as Black Mirror? It could be all of these to some extent. Or none of them, and I just didn't get it. Whatever it is, it's an intriguing film, but I didn't care enough to want to be right about it.

Léon Morin, prêtre - Jean-Pierre Melville (1961)

I was very surprised by this film, as I didn't expect to enjoy it so much. The story takes place during the Vichy Republic in France. Barny (Emmanuelle Riva) is an intelligent young woman who is quite progressive for her time: Marxist, atheist, single mother and bisexual (although this label is not used in the film). Driven by morbid curiosity and a certain intellectual arrogance, she goes to the confessional, but instead of offering a confession to the priest, she decides to question him theologically. To her surprise, Father Morin (Jean-Paul Belmondo) proves to be an intellectual adversary worthy of her. From this encounter, they develop a friendship based on philosophical and theological conversations and readings.

I can't say what the outcome of this relationship was, but it has a lot in common with Fleabag. The performances of the protagonists are wonderful, and the film's script is fantastic (especially considering that much of the film consists of conversations). In short: I loved Léon Morin, it will definitely be one of my favourites of 2025.

MUSIC & PODCASTS

A Little Touch of Schmilsson in the Night - Harry Nilsson (1973)

This album brings me immense peace. I listened to it a lot this month while writing or walking down the street. They are folk-style jazz covers of Harry Nilsson, whom I adore. For those who don't know him, he has a vibe similar to Nick Drake, Donovan, Cat Stevens, Graham Nash, etc. The cover of ‘It Had to be You’ is my favourite, mainly because it is one of my favourite songs.

It Appears that Children were Left Behind - Bitchtopia Podcast

An equally important and depressing discussion about the current state of the relationship that children and teenagers have with literature. Based on testimonials from educators and extensive research, the girls at Bitchtopia managed to alarm me greatly — nothing I didn't already know, but it's worse when you discover concrete data. And another thing: the education system of the United States is one of the most dreadful and absurd things I’ve ever seen in my life. Unfortunately, it explains a lot. I particularly recommend it for those who have or intend to have children (or work educating children) and want to raise them to be functional beings.

Siboney - Playlist

I don't remember how I found this playlist on Spotify, but I was obsessed with it. Particularly good for listening to while cooking. According to the playlist's creator, it is ‘something beyond Lynchian and not quite Americana.’ Whatever that means!