Favourite Books from a Very Critical Person - part 1

It's hard for me to consider a book a favourite. Let's discuss the ones that made the list

In September, this newsletter will be three years old, and I realised that in all that time, I've never discussed one of the most beloved (and obvious) topics within the literary community, namely: my favourite books.

Although I'm quite critical and hardly ever give the title of favourite to a book, over the years I've accumulated a fair number, and if I were to talk about all of them in detail, the post would be too long. That's why this will be a series in parts, in chronological order, that is, from the oldest to the most recent favourites.

Usually, a book becomes a favourite unexpectedly, by stirring my intellect and emotions in an equally strong way. A few requirements for a favourite are:

It needs to challenge me to some degree: I like the feeling of conquering or overcoming a difficult book (mind you, there are many types of difficulty); if not the book itself is overcome, maybe my prejudice against the book (it happened with Leaves of Grass)

It must affect me deeply: I need to CARE about the story and the characters almost as if they were real people (Tolstoy is the best at it). In case of poetry or non-fiction, the writing must do the emotional stirring job

It has to broaden my knowledge: I love learning, so I appreciate when a book is full of references to places, art pieces, history, philosophy, mythology… also, I love picking up on the author’s writing techniques (I learned a lot from Joyce in that way)

Ideally, it will change (or at least question) the way I think about something: for instance, The Goldfinch and The Picture of Dorian Gray forever altered the way I conceive, enjoy, and understand Beauty and Art.

I love discovering people's favourite books and why they love them so much, so I hope you enjoy this list. Above all, I hope it encourages someone to read at least one of these works that have changed my life.

Pride and Prejudice - Jane Austen

My mother gave me a beautiful edition of this book on my 16th birthday, because I was (and still am) completely obsessed with the film starring Keira Knightley and used to watch it with alarming frequency. She had read it herself as a teenager and was sure I would enjoy it. I confess that I didn't love it at first and it took me a long time to finish, as this was the first ‘real’ classic literature book I had read; until then, my literary diet consisted of Agatha Christie, John Green, the Harry Potter series, and random crime thrillers (such as those by Dan Brown and Stieg Larsson).

Therefore, Jane's language was a challenge for me at first. But I didn't give up because 1. I am incapable of DNF books, and 2. I knew there was something beautiful there, even if I didn't understand everything. I have always been someone who likes to reread books (famously, I have read The Half-Blood Prince nine times), and on a second attempt the following year, I was seeing this book with new eyes.

Pride and Prejudice changed my life because it introduced me to classical literature, to the point that, ten years later, it made me want to turn the study of this literature into a career. Jane Austen is an absolutely unique writer in terms of her narrative technique, which moves smoothly from the exterior to the interior of a character, her use of humour and irony, and her creation of simple but deeply engaging narratives thanks to her extremely memorable characters. I have never found another writer who provides me with the Austenian experience except Austen herself: she has the gift of making me value what is familiar and cosy, and of convincing me that love is real. To date, I have reread this book four times and always discover some detail that only increases my admiration for the author. It is worth mentioning that I love all of her novels, this one being my favourite.

I have never written about Pride and Prejudice, but I have written about Mansfield Park, if you’re interested:

The Ethics of Space in Mansfield Park

Thus the house is not experienced from day to day only, on the thread of a narrative, or in the telling of our own story. Through dreams, the various dwelling places in our lives co-penetrate and retain the treasures of former days. – Gaston Bachelard

Notes from the Underground - Fyodor Dostoevsky

This one has an amusing anecdote behind it. When I was in high school, I had a creative writing teacher who was the absolute worst — not only as a person (because he was cruel and condescending) but also as a professional (since he was awful at his job). At the beginning of the semester, he gave us a list of books he considered “real literature”: your typical Orwell, Vonnegut, Hemingway, etc. He told us we had to pick one of these and write a critical review about it, due in a couple of months.

Objectively, this is a great assignment. However, he delivered it in the worst possible manner: he belittled any and all kinds of modern and “teen” literature using a truly despicable language, and even tried to embarrass a few students on the spot, by asking them what they were reading (if the answer was Percy Jackson or Harry Potter, he would start crashing out) and if we knew any of the books on the list (if we didn’t, we were downright stupid). Needless to say, everyone hated that guy, especially me, who had always been so proud and sure of my intellect.

So proud, in fact, that it was now a point of honour to prove him wrong about me: Just because I was reading Harry Potter, it didn’t mean I was an uncultured idiot. I went home and asked my father which one was the most difficult book on the list, and he said, “Probably the one by Dostoevsky”, which he had in his office. I started reading it on the same day, and lo and behold: my brain was in shock. By reading Notes, I discovered things I didn’t know literature could do. The level of self-awareness from the narrator (not least the amazing aspect of a book being conscious of its media form) and the blunt honesty through which sentiments were conveyed left me stunned. I genuinely had no clue a book could be so good, so interesting. By now, I’ve reread this novella three times, and also read The Double and Crime and Punishment by Dostoevsky — both were also challenges I enjoyed, but not as much as Notes.

I never forgot this episode for two reasons. One, because I want to teach literature someday (and I kind of do through my online platforms), and this man chose the worst method possible to make students engage with literature. I wouldn’t be surprised if some of my colleagues developed an aversion to books on that day. What is even worse is that his list was great. But he perpetuated the most awful cliché about literary elitism, ruining almost every chance for us to take his assessment seriously or even with pleasure. I could only think of how differently I would have done it (and will do). The second reason is that, because of his contempt and my wounded pride, I discovered one of the most amazing pieces of literature I’ve ever read. So in a twisted way, I should thank him. But I won’t.

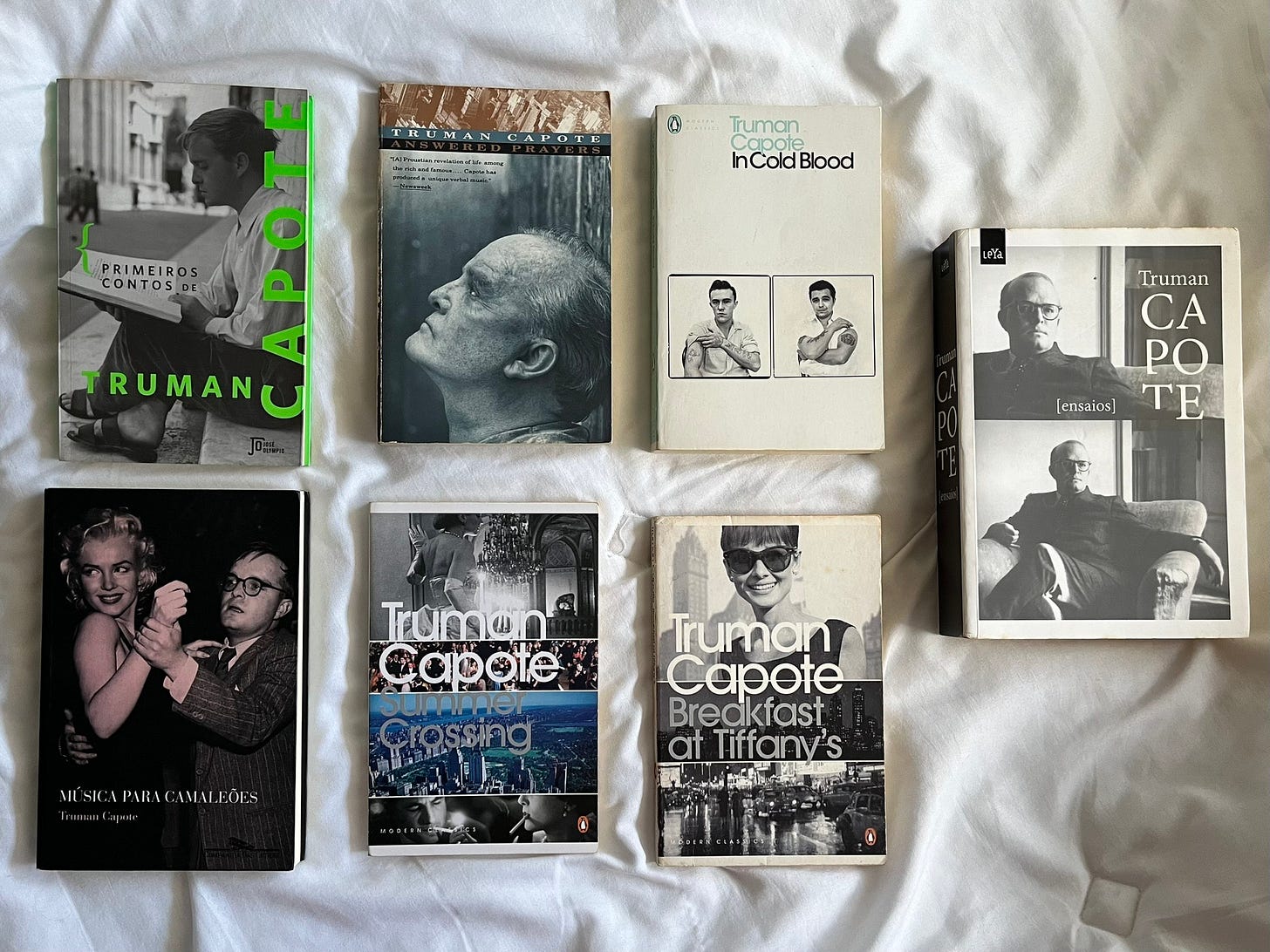

Music for Chamaleons - Truman Capote

During the pandemic in 2020, my university suspended activities for seven (!) months (not even online teaching), and for the first time ever I found myself with nothing to do. No obligations, no deadlines, nothing to study. So I did what every nerd must do, and took the time to read every book I owned. And I did. Now I needed new ones.

For my birthday, I asked my parents for a list of books (which they ordered online), and in this list was Music for Chamaleons by Truman Capote. I was going through a bookish awakening at the time; during my first year of Uni (2019), I lost the habit of reading for fun, and now, with the imposed lockdown, I had the opportunity to rediscover that hobby, so I was spending a lot of time on booktube.

I discovered many new authors and titles via booktube, and one of them was Truman. I fell completely in love with him after Music for Chamaleons, and now I’ve read almost everything he ever wrote. This book is so difficult to describe or even categorise. It’s part autofiction, part journalism, part short story; Truman recounts real events (such as lunch with Marilyn Monroe after a funeral) but embellishes them with fanciful details, and the charm lies precisely in not knowing what is true and what is illusion. He is such a witty, blunt, intelligent, and funny writer — I feel like I’m having drinks with a long-distance friend every time I read one of his books. Yet again, I discovered with Music for Chamaleons new writing possibilities; it’s astonishing how many things one can accomplish through literature, how many tricks and techniques exist. Truman taught me to write, and not only that, but he instigated me to write. When I’m working, I always have three authors on mind: Capote, Hemingway, and Didion.

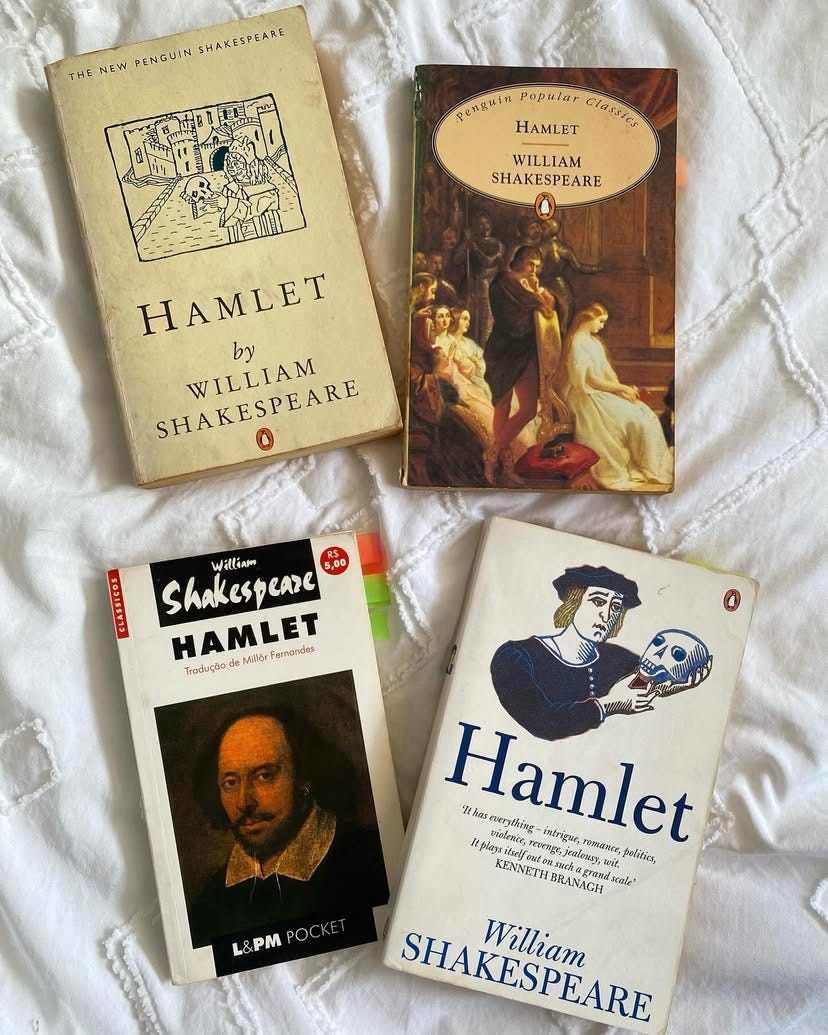

Hamlet - William Shakespeare

Even though it's not exactly a book, if you asked me, I would say that Hamlet is my favourite book. People are probably tired of hearing me say that ‘everything is Hamlet,’ but everything IS Hamlet. I mean, countless literary, cinematographic, and even musical works have some reference to Hamlet — just pay attention and you'll start seeing Hamlet everywhere.

I read this play for the first time also during the pandemic, and I recall the feeling it gave me, which was similar to an epiphany. It was a shock to discover that, indeed, this work, which everyone said was one of the greatest achievements of Western literature, was truly incredible. Who would have thought!

To date, I have read Hamlet seven times, and I promise that every rereading reveals a new aspect or feeling. The last time I reread it, in May of this year, I found the play funnier than I remembered: I remember laughing much more than I cried (and I always cry when Hamlet says to Ophelia, ‘get thee to a nunnery’). I memorised the ‘To be or not to be’ monologue four years ago and can recite it. I've seen five adaptations, as well as Tom Stoppard's incredible Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead. Hamlet sparked a love for Shakespeare that led me to choose to study him in my undergraduate thesis (on Richard II), and I plan to specialise in Shakespeare at graduate school. Having to do a seminar on Hamlet in my Theatre History class was what inspired me to create this newsletter (that's where the name ‘Methinks’ comes from), and you can read my essay (and the first essay I published — and since it’s the first essay, BE NICE) here:

The Undiscovered Country: an analysis of the supernatural in "Hamlet"

I want you to imagine that you are the only child of a mighty father, a man who is the epitome of ideal masculinity, he is determined, a conqueror, and he is everything that you want to be, but are not quite sure you’ll be able to. You are his sole heir, and there are heavy expectations on your shoulders. However, you are not like him, are you? No. You …

Hamlet is one of my greatest obsessions, and it certainly changed my life because it gave me direction; nothing makes me happier than studying Shakespeare. I hope to one day translate the Bard's plays into Portuguese, my mother tongue.

Já tentei ler Orgulho e Preconceito porque também gosto do filme mas achei chato demais 😿 agora Hamlet deu vontade de ler só por causa desse seu relato hehe!

https://therepublicofletters.substack.com/p/an-interview-with-marilyn-simon-part?r=4lf3oc&utm_medium=ios