Favourite Books from a Very Critical Person - part 2

It's so hard to make a list of favourites

After three years of running this newsletter, I realised that in all that time, I've never discussed one of the most beloved (and obvious) topics within the literary community, namely: my favourite books.

Although I'm quite critical and hardly ever give the title of favourite to a book, over the years I've accumulated a fair number, and if I were to talk about all of them in detail, the post would be too long. That's why this will be a series in parts, in chronological order, that is, from the oldest to the most recent favourites.

If you missed part 1, you can check it out here:

Favourite Books from a Very Critical Person - part 1

In September, this newsletter will be three years old, and I realised that in all that time, I've never discussed one of the most beloved (and obvious) topics within the literary community, namely: my favourite books.

I love discovering people's favourite books and why they love them so much, so I hope you enjoy this list. Above all, I hope it encourages someone to read at least one of these works that have changed my life.

The Secret History - Donna Tartt

This is one of the rare cases in which a thing is worth its hype. I read The Secret History in 2020 for the first time — I liked it, but I thought it was a bit underwhelming. Then I read it again in 2022 and LOVED IT. I think I needed a little more literary experience to appreciate it as it deserves, and in those two years, I read a lot, mainly classical literature.

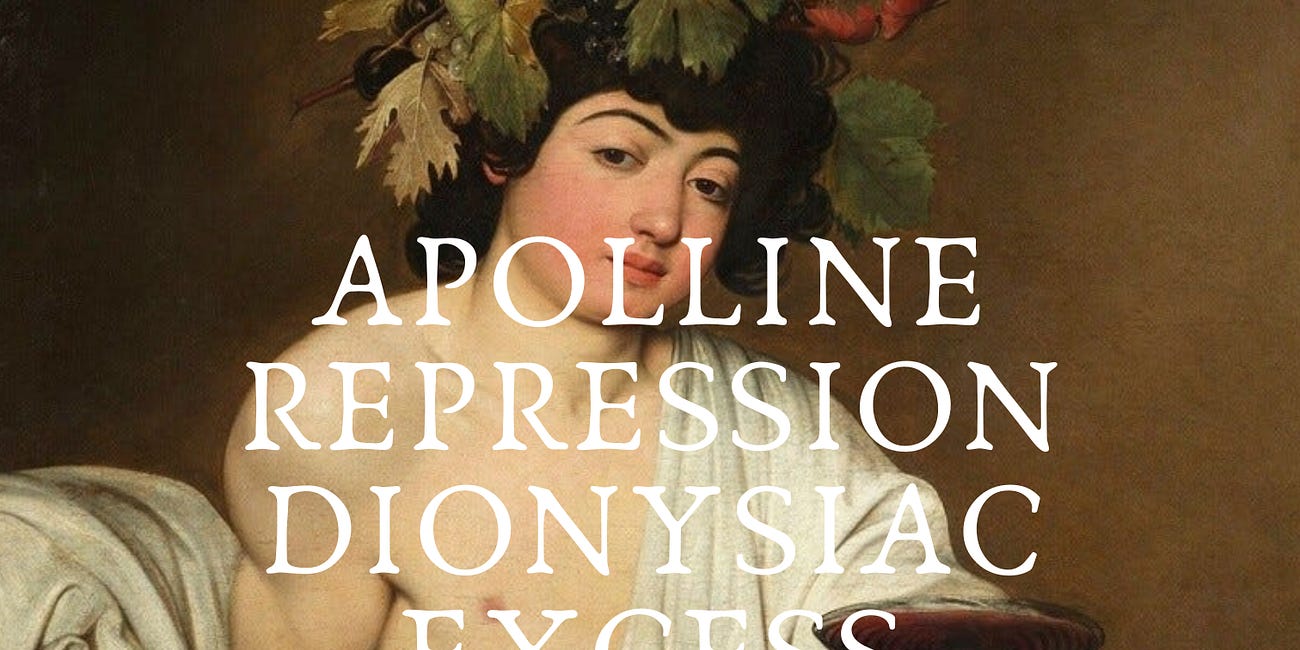

This book explores issues of veracity in identity through a first-person narrator who does not possess all the facts, and the repression of the Self’s impulses, based primarily on the parallel between the Dionysiac and the Apolline developed by Nietzsche in The Birth of Tragedy. I wrote a long essay about it:

Apolline Repression and Dionysiac Excess: uncovering 'The Secret History' by Donna Tartt

Here, in this supreme menace to the will, there approaches a redeeming, healing enchantress – art. She alone can turn these thoughts of repulsion at the horror and absurdity of existence into ideas compatible with life — Friedrich Nietzsche, The Birth of Tragedy

The Secret History is a book that can be reread several times, and there will always be something new to uncover — a characteristic that all my favourite books have in common. Tartt's writing is sublime and reflects the most famous maxim of her work, ‘Beauty is Terror’, as it balances the beauty of prose that clearly carries on the tradition of the canon with sombre undertones, which are used to create the eerie atmosphere the book is so famous for (and which was labelled as “dark academia”).

The novel follows a group of students at a small liberal arts college in Vermont, from the perspective of one of them: Richard Papen, a kind of obscure Gatsby; an outsider from California who desperately strives to belong to that group he considers the cultural elite, the opposite of everything he knew in his youth. From the outset, we know that one of them dies, but we don't know why. Tartt subverts the mystery genre by revealing the murderer and the murdered on the first page, and her challenge as a writer is to keep the reader engaged for 500 pages to discover the motive for the crime (and its consequences). I must say that the challenge is met with stunning success. It is disturbing and entertaining in equal measure, and the image of the body lying dead in the snow is one of the most unforgettable opening scenes in contemporary literature.

The Picture of Dorian Gray - Oscar Wilde

From all the books on this list, this may be the one that changed my life the most. This book, and especially its preface, gave me an answer to my obsessive interest in Beauty — it gave me an aesthetic philosophy, one that still influences me to this day. I’ve read this book twice, and I think I should make it a rule to read it every year.

Beauty as an entity, the importance of art in human life, the question of morality in an artwork, the power and corruption one can find in passion, and the role the artist must take in society — all of these themes can be found in Dorian Gray. At the centre of this strange philosophical novel, there is a Faustian pact made by the young and beautiful Dorian — somewhat unwittingly — to maintain his beauty and youth. The years go by and he stays the same, yet only on the outside. As his character suffers a moral decline, his portrait holds evidence of his decay: the more evil Dorian gets, the uglier his picture. Wilde certainly had a moral agenda with this ominous fable — which is sometimes written as a Socratic dialogue to my delight, Lord Henry taking the role of Socrates — yet it is often misunderstood.

According to Joyce Carol Oates, “Wilde surely believes in his aesthetics and at the same time offers, by way of Dorian and his fate and Basil and his fate, a disturbingly prescient commentary on his beliefs: the artist who succumbs to the spell of beauty will be destroyed, and so savagely destroyed that nothing of him will survive. The novel's power lies in the interstices of its parable — in those passages in which the author appears to be confessing doubts of both a personal and an impersonal nature.” Wilde knew that his intense obsession with Beauty could lead to his downfall (as it did to his character), and he paid the price for it. I may be romanticising it, but I don’t think a well-balanced man could have produced the kind of art Wilde did.

Wuthering Heights - Emily Brontë

Wuthering Heights is equally strange and genius. The novel not only incorporates elements from a number of genres — such as gothic and bildungsroman — but also questions those different elements by creating a tension between them. There are classical and romantic influences used as tools for a profound expression of Emily’s intense imagination. The novel is as suffocating as a nightmare, specifically when you know you’re in a nightmare but can’t wake up.

Although it might look like a love story at times, this is no romance. I see it as a modern dark fairytale, with aspects of romance, although that are many other interpretations. It is precisely this original combination of elements from different genres that makes this book so difficult to define, and consequently to understand, since there are no parameters into which the reader can fit it accurately.

I remember the perplexity I felt when I read Wuthering Heights for the first time — it is difficult to settle into that isolated world among the English moors. The reader is practically a character, represented by the figure of the new tenant: an outsider who seems to stumble upon a path he should not have taken, and in the detour he finds in the mysterious forest, he enters a parallel reality, a fantastic world of ghosts, where memories are embodied through the typical repetition of the Gothic: the proliferation of Cathys, Lintons and Earnshaws reinforces the feeling of seclusion, of inescapable and cursed destinies.

This book is dense, beautiful, and sad. It is a challenge, but one that is absolutely worth it.

Anna Karenina - Leo Tolstoy

Look no further, this is The Perfect Novel. Tolstoy is the most gifted author I know when it comes to creating characters that feel real. I miss people from his novels as if they were my friends and lovers (Levin, Helene, Andrey, Anna…). I spent two months in 2021 reading nothing but this novel, and it was such an incredible and immersive experience that I did the same in 2022 with War and Peace.

Anna Karenina is about much more than Anna herself. Of course, she is the thread that connects that fantastic web of characters, but this book is more like a piece of 19th-century Russia fossilised on paper: it is the truest example of reading as time travel. It would be useless and unworthy to try to summarise the plot of Anna Karenina. Suffice it to say that there are two love stories, one tragic and one happy, but a very realistic happiness; portraits of dysfunctional families, some devastating, others joyful; a lot of social, economic and political commentary on the country (Tolstoy is famous for including chapters in his novels that are basically treatises — I don't like how he did this in War and Peace, but I like it in Anna Karenina).

Until I read Anna Karenina, I had no idea how much a book could affect me emotionally (when you stop to think about it, it's kind of weird to cry so much over words on paper about unreal events), but I think that's the beauty of literature. I was heartbroken by the ending, but at the same time very satisfied to have read something so well done and impactful. It really is a masterpiece like no other, and of all the books on the list, this is the one I would insist you read.

So, basically, we can be best friends :) love this!

Me sinto tão chique compartilhando esse top 4 com você…