Methought - February/2025

Monthly wrap-up: Oscar best picture nominees, reading Plato for fun (?), back to T.S. Eliot, and discovering the meaning of Radical Chic (2025 will be the year of Radical Chic I can feel it)

scroll down to read the English version

Caros leitores,

O ano está passando rápido demais. Quando me dei conta já era março e eu ainda estava escrevendo sobre os acontecimentos de fevereiro. Foi um mês de altos e baixos e de recalcular rotas mais uma vez. Não aguento mais recalcular rotas e refazer planos!!! Mas viver é isso, não tem o que fazer. Pelo menos eu tenho bons livros e Joni Mitchell para me consolar.

O poema do mês foi escrito por E.E. Cummings; é extremamente romântico e não sai da minha cabeça, tanto que me fez comprar um livro dele:

[somewhere i have never travelled,gladly beyond]

somewhere i have never travelled,gladly beyond

any experience,your eyes have their silence:

in your most frail gesture are things which enclose me,

or which i cannot touch because they are too nearyour slightest look easily will unclose me

though i have closed myself as fingers,

you open always petal by petal myself as Spring opens

(touching skilfully,mysteriously)her first roseor if your wish be to close me,i and

my life will shut very beautifully,suddenly,

as when the heart of this flower imagines

the snow carefully everywhere descending;nothing which we are to perceive in this world equals

the power of your intense fragility:whose texture

compels me with the colour of its countries,

rendering death and forever with each breathing(i do not know what it is about you that closes

and opens;only something in me understands

the voice of your eyes is deeper than all roses)

nobody,not even the rain,has such small hands

LIVROS &TC.

The Waste Land & Other Poems - T.S. Eliot (1922)

Normalmente, gosto quando uma obra artística contém referências implícitas a outras obras, porque me sinto um detetive desvendando novas camadas de significado até atingir um momento de esclarecimento por meio dessas peças-chave. Acho esse processo muito divertido. Contudo, existem obras em que a quantidade e o tipo de referência alienam o leitor, como é o caso de The Waste Land, talvez o maior poema do modernismo inglês.

De acordo com o Prof. Nick Mount, as alusões presentes em The Waste Land são como um teste: o leitor que captar uma quantidade suficiente delas poderá compartilhar do desespero de Eliot, pois, obviamente, conhece a cultura cuja morte o autor lamenta ao longo do poema. Há uma grande desordem intencional em The Waste Land — pode-se dizer que o poema é polifônico, talvez representando a desordem sentida pelo autor ao viver no início do século XX, depois de uma guerra que não só devastou fisicamente a Europa, mas também destruiu a ordem e o sentido de toda a sociedade; foi o derradeiro fim da era vitoriana e de todos os seus valores.

A sensação de confusão diante do abismo é algo que se pode sentir no poema, independentemente das alusões. Colocando esse sentimento no contexto do modernismo e de tudo que ele representa, é possível enxergar uma luz no poema. Apesar de toda a dificuldade caótica, há uma ordem incrivelmente meticulosa na desordem construída por Eliot — ele é do tipo de escritor que faz você sentir que nenhuma palavra foi dita em vão.

Mestres Antigos - Thomas Bernhard (1985)

Mestres Antigos é um livro repleto de contradições intrigantes. Em um museu austríaco, sentados diante do Homem de Barba Branca, de Tintoretto, os amigos idosos Reger e Atzbacher tentam encontrar beleza e sentido em meio à absurdez da modernidade e ao amargor pessoal, mesmo que essa busca resulte em frustração. Reger mergulha em uma crítica mordaz à sociedade austríaca, especialmente à forma como o Estado e suas instituições moldam a arte de maneira opressiva e impositiva. Segundo ele, as grandes obras exaltadas pelo museu não passam de veículos de uma moralidade estéril, que não provocam inquietação ou deslumbre, mas apenas reforçam uma contemplação passiva. Para Reger, o museu onde essa conversa ocorre é um reflexo do próprio Estado austríaco: católico, moralmente corrupto e herdeiro de um passado opressor.

Essa frustração intelectual e estética, no entanto, não é apenas uma questão teórica. Ao longo do livro, percebe-se que sua revolta tem um motivo pessoal profundo, e a crítica social se entrelaça de maneira indissociável ao sofrimento particular de Reger, tornando-se impossível separar uma coisa da outra. O conflito interno de Reger se resume em uma epifania piegas: por mais espetacular que seja o objeto artístico, ele jamais substituirá a conexão humana. Ele percebe, a contragosto, que o inferno são os outros, sim, mas que, sem esse inferno, não sobrevivemos. Esse desfecho surpreende por conter uma nota de esperança, o que me agradou bastante. Criar um personagem que odeia tudo e se render ao desprezo absoluto é fácil; difícil é fazê-lo admitir o horror e, ainda assim, não se entregar completamente a ele. Essa é a genialidade de Bernhard nesse livro excelente.

A República - Platão

É um tanto frustrante ler isso na expectativa de desvendar algum grande segredo ancestral sobre as questões básicas do mundo. Na verdade, boa parte do livro se revela um emaranhado de falsas analogias e argumentos contraditórios — o que, convenhamos, faz sentido, já que, na época, não havia o rigor metodológico que hoje consideramos essencial para embasar qualquer proposição ou teoria filosófica. Além disso, achei curioso como a República idealizada por Platão (em nome de Sócrates) parece muito mais uma distopia do que uma utopia, especialmente pela insistência em censurar poetas e artistas, pela condescendência com que o livro trata “as massas” e pela excessiva invasão do controle estatal na esfera privada. Sou muito a favor de um Estado grande, mas, na República, ele é grande demais, a ponto de controlar até com quem você vai se casar.

Ainda assim, como defensora da ideia de que só se pode criticar algo com propriedade depois de conhecê-lo a fundo, considero A República uma leitura fundamental. Afinal, foi desse livro que brotaram ou foram rebatidas incontáveis ideias filosóficas: o gnosticismo não existiria sem a visão de Platão sobre as “camadas” de realidade no universo; a teoria das formas é bem útil para entender as bases da semiótica (ideia do objeto em si > objeto > representação do objeto); e até a teoria dos jogos, que sustenta boa parte da filosofia política, de Rousseau a Hobbes, tem origem nesse livro. Platão conseguiu abarcar praticamente todas as áreas do conhecimento, e isso, sem dúvida, é impressionante. Não concordo com muita coisa, mas terminei a leitura feliz (e orgulhosa), até porque o final é inesperadamente poético — o que, ironicamente, vem depois de páginas e mais páginas de desprezo pela poesia.

ARTIGOS, ENSAIOS, PALESTRAS &TC

Radical Chic - Tom Wolfe para a New York Magazine (1970)

Imagine um apartamento gigante no Upper East side nos anos 1970 e, durante uma não-festa (os anfitriões insistiram que não era uma festa) para promover a causa antirracista, o cineasta Otto Preminger está discutindo acaloradamente (e comicamente) com um dos líderes dos Panteras Negras, enquanto milionários liberais, artistas e ativistas assistem.

Esse é o cenário absurdo do evento que ficou marcado na cultura pop nova-iorquina, ocorrido na casa do Maestro Leonard Bernstein e relatado com maestria pelo ícone do new-journalism americano, Tom Wolfe. Através desse relato, Wolfe na verdade questiona: o que acontece quando a elite busca se apropriar de pautas da contracultura, seja por estilo ou absolvição moral? O resultado é o que Wolfe chama de “Radical Chic”, um termo semelhante ao que eu chamo carinhosamente de “burguesia cirandeira”. É um texto bastante longo mas vale a pena ser lido, pois além de ser divertidíssimo foi um marco na história da New York Magazine, que na época estava apenas começando.

So many unmarried men - Ellie Robson para Aeon Magazine (2025)

Uma característica comum e infeliz que percebi ao ler diversas obras de filósofos clássicos ocidentais é o tratamento desdenhoso ou mesmo ressentido do amor e dos relacionamentos, da paixão ao matrimônio. Platão compara estar amando a estar doente ou bêbado, em A República, e Nietzsche descreve as mulheres como sedutoras superficiais que só sabem desviar os homens do caminho da iluminação intelectual, em Assim Falou Zarathustra. Esses são apenas alguns exemplos, e não é de se surpreender que esses filósofos — e muitos outros, de Spinoza a Kant — nunca tenham se casado (para fins de um argumento que faça sentido na vida contemporânea, leia-se “casar” também como se apaixonar, ter um affair, uma companheira de vida etc.).

A filósofa Mary Midgley argumentava que a ausência de relações pessoais significativas poderia levar filósofos a conceberem a filosofia como uma atividade excessivamente abstrata e distante, desvinculada da experiência humana prática e afetiva — uma abordagem que se afasta da noção tradicional de um intelecto “puro” e “não corrompido” pelas emoções e sensações (algo associado à feminilidade e, portanto, desprezado). Em vez de descartar esses fatores como meramente subjetivos, perspectivas feministas defendem que eles são elementos essenciais do processo de conhecer e compreender o mundo. Nesse contexto, surge o conceito de “injustiça epistemológica”, que ocorre quando uma pessoa, ou um grupo de pessoas, é excluído das práticas que moldam o significado e as normas na sociedade.

Midgley no livro Rings and Books:

“Philosophers need above all to concentrate. They are not like poets (nearly all good poets marry, however madly). What they most need is space for thought … Because independent thought is so difficult, the philosophic adolescent (even more than other adolescents) withdraws himself from the influences around him to develop ideas in harmony with his own personality … The great philosophers did not return [from this withdrawal]. Their thoughts, unlike yours and mine, had powers enough to keep them gazing into the pool of solitude.”

Left-Wing Irony: An alternative to the politics of contempt - Jessi Jezewska Stevens for The Point (2025)

Este artigo parece sugerir que a direita atual está votando contra o estilo esquerdista, para além dos ideais políticos. Isso significaria que, além dos inúmeros fatores citados no texto, os retrocessos da esquerda em todo o Ocidente também se devem, em parte, à sua postura retórica — à sua insistência em se apegar a um vocabulário de superioridade moral que implica desprezo pelas próprias pessoas que tenta persuadir. Isso não é mera crítica estética. A maneira como nos dirigimos uns aos outros não é uma questão secundária; é a esfera pública.

Não é porque sou de esquerda que vou deixar de criticar e apontar suas falhas (na verdade, interpretar crítica como traição é um dos grandes empecilhos retóricos que estamos enfrentando em diversos movimentos políticos, inclusive dentro do feminismo). No meio acadêmico, por exemplo, conheço vários jovens conservadores desiludidos com a cultura contemporânea e com as relações digitais superficiais — algo que o texto destaca e com o qual acho que todos nós podemos nos identificar. Eles buscam no pensamento pós-liberal católico um sentido mais profundo para suas vidas e, assim, são atraídos para a direita moderna, que, em alguns meios, está mais alinhada com essa busca de significado. Stevens questiona, de forma muito pertinente, se a esquerda conseguirá oferecer uma alternativa convincente para esse sentimento de vazio. Não concordo com tudo que foi argumentado (até porque é uma perspectiva muito USA-centered), mas vale a leitura pelos questionamentos levantados.

Preferring to pose as a “spiritual elite” rather than actively engage with the labor movement, [the left] were guilty of a “grotesque underestimation of the opponent” (in this case, capitalism). Where their ideals used to be, Benjamin lamented, there lay only “the empty spaces where, in dusty heart-shaped velvet trays, the feelings—nature and love, enthusiasm and humanity—once rested. Now the hollow forms are absentmindedly caressed” with a “know-all irony” that “turns the yawning emptiness into a celebration.”

FILMES & SÉRIES

Conclave - Edward Berger (2024)

Apesar de lembrar um pouco Dan Brown em certos momentos — especialmente na revelação final — gostei bastante de Conclave, mais pelas atuações e pela fotografia do que propriamente pelo roteiro. Gosto de histórias que exploram crises de fé, e, para mim, o ponto alto do filme foi o discurso de Ralph Fiennes sobre a certeza. No entanto, depois senti que essa reflexão não foi plenamente incorporada à trama com a profundidade que merecia. Apesar de ter saído do cinema com uma impressão positiva, acho que será um filme facilmente esquecível para mim.

Anora - Sean Baker (2024)

Gostei muito de Anora mas não achei genial tal qual a Academia do Oscar certamente achou. É um filme que aborda um assunto perturbador por trás de uma superfície humorística, um formato que normalmente aprecio se feito da forma correta. Quanto às as cenas mais desconcertantes (por exemplo, quando os russos prendem Anora na mansão) eu estava rindo no cinema e triste em retrospecto — isso é digno de mérito, pois não é fácil de realizar, nem para quem escreve o texto nem para quem o interpreta. A fantasia de cinderella frustrada a partir da desilusão romântica e econômica é uma história que, para mim, já estogou as possibilidades de inovação narrativa. Talvez por isso eu não tenha sentido tanto o impacto de Anora e me vejo até agora sem ter muito o que dizer sobre. Este é um filme sobre “the erotics of class ascendency”, como disse Rayne Fisher-Quann num ensaio bem interessante que você pode ler aqui:

O Brutalista - Brady Corbet (2024)

Meu favorito entre os indicados a Melhor Filme no Oscar. Gosto de filmes grandiosos em sua forma e gosto da autoimportância que O Brutalista se dá, pois ele entrega o que insinua. Antes de mais nada, fui completamente atraída pela combinação sensorial de sons e imagens: ser filmado em VistaVision realmente fez uma diferença estética tremenda, e a sequência de abertura, com aquela trilha sonora excelente, me impressionou desde o início. Vi alguém dizendo que esse filme, em termos de forma, era equivalente a The Great American Novel, e eu concordo. Por exemplo, East of Eden deveria ser filmado desse jeito para transmitir com precisão o sentimento do romance.

Narrativas sobre a farsa do American Dream são batidas, sim, mas esse aspecto clichê não tirou meu encantamento. Por mais grandioso que o filme seja (e por mais que isso faça com que ele abandone certas tramas ou use personagens como plot devices), muitas vezes ele brilha nos detalhes — a viagem à Itália para buscar o mármore de Carrara, por exemplo, foi o destaque do filme para mim. Havia algo sombrio e inóspito na sequência em que os personagens vagueiam entre aquelas montanhas, principalmente pela menção às cavernas de mármore sem saída, onde o povo abandonava prisioneiros; me deu arrepios. Só não gostei muito da cena final, que se passa nos anos 1980 — acho que estragou um pouco a conclusão da história.

A Complete Unknown - James Mangold (2024)

Confesso que eu estava pronta para detestar esse filme pois (1) não aguento mais biopics e (2) não tinha gostado de escolha de atores para Bob Dylan e Joan Baez (até porque eu sou completamente obcecada por Joan). Porém, fui supreendida positivamente e acabei me divertindo muito durante o filme. Difícil não cantar no cinema (tanto que cantei, sinto muito para quem senta perto de mim eu não tenho pudor) e Timothee realmente está ótimo no papel — até meu pai, que é músico e um grande fã de Bob Dylan, disse que as versões musicais de Timothee estavam melhores que as originais (achei exagero…).

MÚSICA & PODCASTS

Modernist Novel - Why Theory Podcast

Esse é um dos meus podcasts favoritos (talvez vocês já tenham notado) e esse episódio é bem interessante. Um ponto de destaque foi a diferença entre o final de um romance modernista e de um romance tradicional do século XIX: o primeiro tem “um final que aponta para si mesmo,” que não necessariamente oferece uma conclusão; o segundo tem finais que oferecem uma conclusão satisfatória, tanto narrativamente como moralmente, trazendo uma resolução absoluta sem passar uma sensação de continuidade. Óbvio que isso não é a regra, mas é um padrão que está de acordo com as desilusões modernistas abordadas em The Waste Land, por exemplo. Vale muito a pena escutar se você se interessa pela história do romance.

It Ain’t Me Babe playlist

Desde que eu assisti o filme de Bob Dylan eu não parei de escutar Bob Dylan — é uma doença, minha irmã não suporta mais me ouvir cantarolar Like a Rolling Stone pela casa. Eu tenho uma obsessão por Joan Baez e pelo relacionamento dela com Dylan há anos, e essa playlist é antiga mas passei a ouvi-la de novo depois do filme.

Clouds - Joni Mitchell (1969)

Eu estou sempre com algum álbum da Joni Mitchell em rotatividade, e o escolhido do momento é Clouds, não tinha o escutado do começo ao fim até recentemente. A música “I Think I Understand” é minha favorita e uma das que eu mais ouvi esse mês. Tem uma letra belissima que me emociona bastante: “Back along the pathway of a troubled mind / When forests rise to block the light / That keeps a traveler sane / I'll challenge them with flashes from a brighter time / Oh, I think I understand / Fear is like a wilderland”

Dear readers,

The year is going by too fast. Before I knew it, it was March, and I was still writing about the events of February. It's been a month of ups and downs and recalculating routes once again. I can't take any more recalculating routes and redoing plans!!! But that's life, there's nothing you can do about it. At least I have good books and Joni Mitchell to comfort me.

The poem of the month was written by E.E. Cummings; it's extremely romantic and won't leave my head, so much so that I bought a volume of his poetry:

[somewhere i have never travelled,gladly beyond]

somewhere i have never travelled,gladly beyond

any experience,your eyes have their silence:

in your most frail gesture are things which enclose me,

or which i cannot touch because they are too nearyour slightest look easily will unclose me

though i have closed myself as fingers,

you open always petal by petal myself as Spring opens

(touching skilfully,mysteriously)her first roseor if your wish be to close me,i and

my life will shut very beautifully,suddenly,

as when the heart of this flower imagines

the snow carefully everywhere descending;nothing which we are to perceive in this world equals

the power of your intense fragility:whose texture

compels me with the colour of its countries,

rendering death and forever with each breathing(i do not know what it is about you that closes

and opens;only something in me understands

the voice of your eyes is deeper than all roses)

nobody,not even the rain,has such small hands

BOOKS &TC.

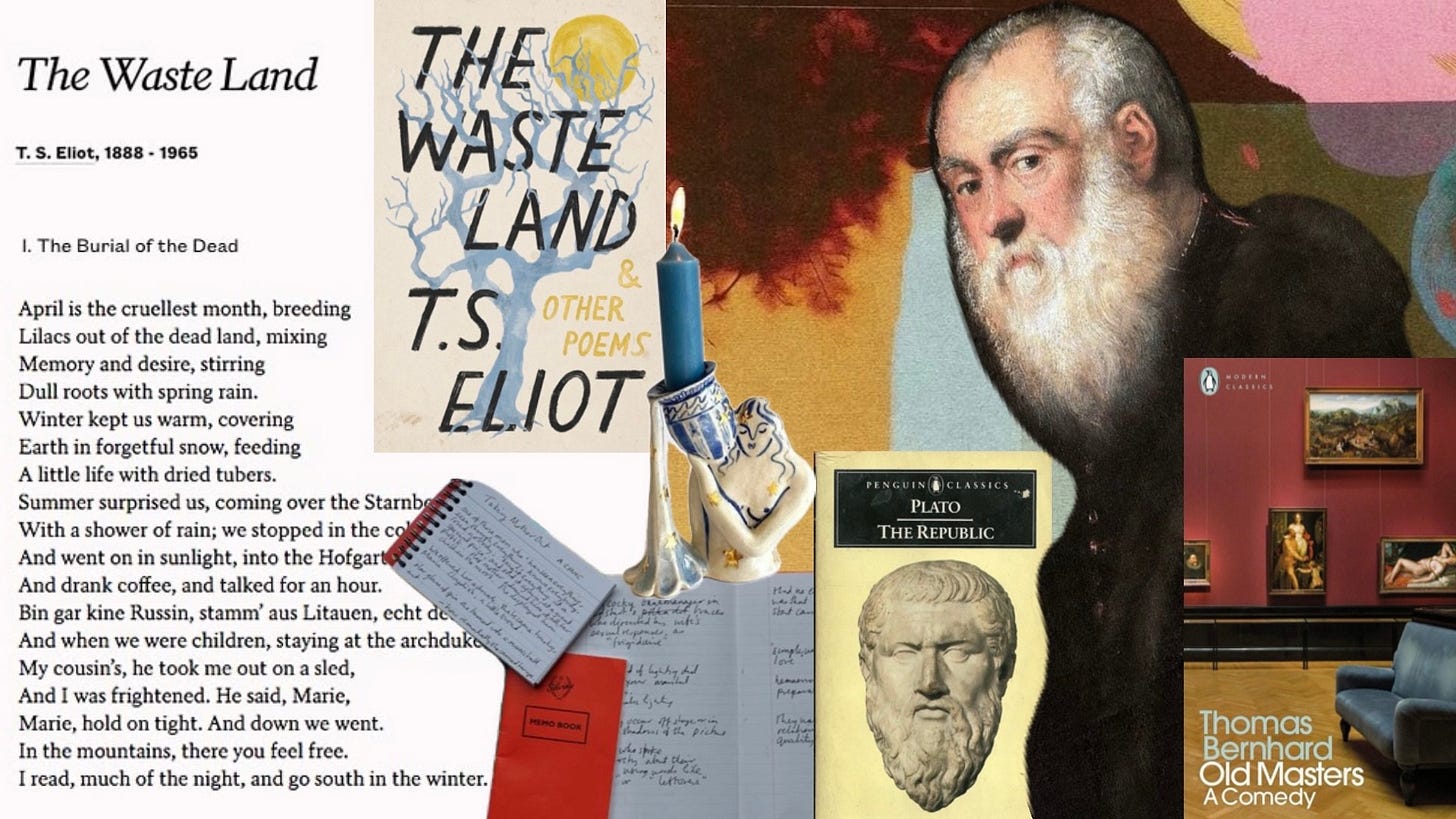

The Waste Land & Other Poems - T.S. Eliot (1922)

I usually like it when an artwork contains implicit references to other works, because it makes me feel like a detective unravelling new layers of meaning until I reach a moment of enlightenment through these key pieces. I enjoy the process. However, there are works in which the amount and type of reference alienates the reader, as is the case with The Waste Land, perhaps the greatest poem of English modernism.

According to Prof Nick Mount, the allusions in The Waste Land are like a test: the reader who understands enough allusions will be able to share Eliot's despair, because this reader obviously knows the culture whose death the author is lamenting through the poem. There is a great deal of intentional disorder in The Waste Land — you could say that the poem is polyphonic, perhaps representing the disorder felt by the author living at the beginning of the 20th century after a war that not only devastated Europe physically, but also destroyed the order and meaning of society as a whole; it was the ultimate end of the Victorian era and all its values.

The sense of confusion looking into the abyss is something you can feel in the poem regardless of the allusions. Putting this feeling in the context of modernism and everything it stands for, it's possible to see some light in this poem. Despite all the chaotic difficulty, there is an incredibly meticulous order to the disorder constructed by Eliot — he's the kind of writer who makes you feel that no word has been said in vain.

Old Masters - Thomas Bernhard (1985)

Old Masters is a book full of intriguing contradictions. In an Austrian museum, sitting in front of Tintoretto's ‘Man with a White Beard’, elderly friends Reger and Atzbacher try to find beauty and meaning amidst the absurdity of modernity and personal bitterness, even if this search results in frustration. Reger plunges into a scathing critique of Austrian society, especially how the state and its institutions mould art in an oppressive and imposing way. According to him, the great works exalted by the museum are nothing more than vehicles for a barren morality, which do not provoke disquiet or astonishment and only reinforce passive contemplation. For Reger, the museum where this conversation takes place is a reflection of the Austrian state itself: Catholic, morally corrupt and heir to an oppressive past.

This intellectual and aesthetic frustration, however, is not just a theoretical issue. Throughout the book, you realise that his discontent has a deep personal motive, and the social critique is inextricably intertwined with Reger's private suffering, making it impossible to separate one from the other. Reger's internal conflict is summarised in a sappy epiphany: no matter how spectacular the artistic object, it will never replace human connection. He realises, begrudgingly, that hell is other people, yes, but without hell, we can't survive. The ending is surprising because it contains a note of hope, which I liked a lot. Creating a character who hates everything and surrenders to absolute contempt is easy; it's hard to get him to admit the horror and still not give in to it completely. That's Bernhard's genius in this excellent book.

The Republic - Plato

It's a bit frustrating to read this expecting to uncover some great ancient secret about the basic questions of the world. In truth, much of the book turns out to be a patchwork of false analogies and contradictory arguments — which, I suppose, makes sense, since at the time there wasn't the methodological rigour that we now consider essential to support any philosophical proposition or theory. Besides, I found it curious how the ‘Republic’ devised by Plato seems much more like a dystopia than a utopia, especially the insistence on censoring poets and artists, the condescension with which the book treats ‘the masses’ and the excessive invasion of State control into the private sphere (I'm very much in favour of a big State, but in the Republic it's too big, to the point of controlling who you marry).

Still, as an advocate of the idea that you can only criticise something properly once you know it thoroughly, I consider The Republic to be essential reading. After all, it was from this book that countless philosophical ideas were born or refuted: Gnosticism wouldn't exist without Plato's vision of the ‘layers’ of reality in the universe; the theory of forms is very useful for understanding the foundations of semiotics (idea of the object itself > object > representation of the object); and even game theory, which underpins much of political philosophy, from Rousseau to Hobbes, came from this book. Plato managed to cover practically all areas of knowledge, and that is undoubtedly impressive. I don't agree with a lot of it, but I finished reading it feeling happy (and proud), not least because the ending is unexpectedly poetic — which, ironically, comes after pages and pages of contempt for poetry.

ARTICLES, ESSAYS, LECTURES &TC

Radical Chic - Tom Wolfe para a New York Magazine

Imagine a giant Upper East Side flat in the 1970s and, during a non-party (the hosts insisted it wasn't a party) to promote the anti-racist cause, filmmaker Otto Preminger is arguing passionately (and comically) with one of the leaders of the Black Panthers, while liberal millionaires, artists and activists look on.

This is the absurd scenario of the event that has become a hallmark of New York pop culture, which took place at the home of Maestro Leonard Bernstein and was masterfully reported by the icon of American new journalism, Tom Wolfe. Through this account, Wolfe is actually asking: what happens when the elite seek to appropriate counter-culture agendas, whether for style or moral absolution? The result is what Wolfe calls ‘Radical Chic’, a term similar to what I affectionately call the ‘folk bourgeoisie’. It's quite a long piece, but it's worth a read because, as well as being entertaining, it was a milestone in the history of New York Magazine, which at the time was just getting started.

So many unmarried men - Ellie Robson para Aeon Magazin

A common and unfortunate characteristic I have noticed when reading various works by classical Western philosophers is a dismissive or even resentful treatment of love and relationships, from passion to marriage. Plato compares being in love with being sick or drunk in The Republic, and Nietzsche describes women as superficial seductresses who only know how to divert men from the path of intellectual enlightenment in Thus Spoke Zarathustra. These are just a few examples, and it's no surprise that these philosophers and many others, from Spinoza to Kant, never married (for the sake of an argument that makes sense in contemporary life, consider marrying to also mean falling in love, having an affair, a life partner, etc.).

Philosopher Mary Midgley argued that the absence of meaningful personal relationships could lead philosophers to conceive of philosophy as an activity that is too abstract and distant, disconnected from practical and affective human experience, an approach that departs from the traditional notion of a ‘pure’ intellect ‘uncorrupted’ by emotions and sensations (something connected to femininity and therefore despised). Instead of dismissing these factors as merely subjective, feminist perspectives argue that they are essential elements in the process of knowing and understanding the world. In this regard, the text introduces the concept of ‘epistemological injustice’, when a person, or a group of people, is excluded from the practices that shape meaning and norms in society.

Midgley in the book Rings and Books:

“Philosophers need above all to concentrate. They are not like poets (nearly all good poets marry, however madly). What they most need is space for thought … Because independent thought is so difficult, the philosophic adolescent (even more than other adolescents) withdraws himself from the influences around him to develop ideas in harmony with his own personality … The great philosophers did not return [from this withdrawal]. Their thoughts, unlike yours and mine, had powers enough to keep them gazing into the pool of solitude.”

Left-Wing Irony: An alternative to the politics of contempt - Jessi Jezewska Stevens for The Point (2025)

This article seems to suggest that the current right is voting against the leftist style, beyond political ideals. This would mean that, in addition to the numerous factors cited in the text, the left's setbacks across the West are also partly due to its rhetorical stance - its insistence on clinging to a vocabulary of moral superiority that implies contempt for the very people it is trying to persuade. This is not mere aesthetic criticism. The way we address each other is not a secondary issue; it's the public sphere.

It's not because I'm from the left that I'm going to stop criticising and pointing out its flaws (in fact, interpreting criticism as a betrayal is one of the great rhetorical obstacles we're facing in various political movements, including within feminism). In academia, for example, I know several young conservatives who are disillusioned with contemporary culture and superficial digital relationships - something that the text highlights and that I think we can all identify with. They look to post-liberal Catholic thought for a deeper meaning to their lives, and so are drawn to the modern right, which in some quarters is more aligned with this search for meaning. Stevens rightly questions whether the left can offer a convincing alternative to this feeling of emptiness. I don't agree with everything that's argued (not least because it's a very USA-centred perspective), but it's worth reading for the questions it raises.

Preferring to pose as a “spiritual elite” rather than actively engage with the labor movement, [the left] were guilty of a “grotesque underestimation of the opponent” (in this case, capitalism). Where their ideals used to be, Benjamin lamented, there lay only “the empty spaces where, in dusty heart-shaped velvet trays, the feelings—nature and love, enthusiasm and humanity—once rested. Now the hollow forms are absentmindedly caressed” with a “know-all irony” that “turns the yawning emptiness into a celebration.”

FILMS & SERIES

Conclave - Edward Berger (2024)

Despite being a little reminiscent of Dan Brown at times — especially in the final revelation — I really enjoyed Conclave, more for the performances and photography than for the script itself. I like stories that explore crises of faith and, for me, the highlight of the film was Ralph Fiennes's speech about certainty. However, afterwards I felt that this reflection wasn't fully incorporated into the plot with the depth it deserved. Although I left the cinema with a positive impression, I think it will be an easily forgettable film for me.

Anora - Sean Baker (2024)

I liked Anora a lot, but I didn't think it was as brilliant as the Academy certainly did. It's a film that tackles a disturbing subject behind a humorous surface, a format that I usually appreciate if done in the right way. As for the more disconcerting scenes (for example, when the Russians trap Anora in the mansion), I was laughing in the cinema and sad in retrospect - this is worthy of merit, as it's not easy to pull off, either for the scriptwriter or the performer. The Cinderella fantasy frustrated by romantic and economic disappointment is a story that, for me, has already exhausted the possibilities for narrative innovation. Perhaps that's why I didn't feel the impact of Anora so much, and I still don't have much to say about it. This is a film about ‘the erotics of class ascendency’, as Rayne Fisher-Quann said in a very interesting essay that you can read here:

The Brutalist - Brady Corbet (2024)

My favourite among the nominees for Best Picture at the Oscars. I like films that are grand in their form and I like the self-importance that The Brutalist gives itself, because it delivers what it claims. First of all, I was completely drawn in by the sensory combination of sounds and images: being filmed in VistaVision really made a tremendous aesthetic difference, and the opening sequence with that excellent soundtrack impressed me from the start. I saw someone say that this film, in terms of form, was equivalent to The Great American Novel and I agree. For example, East of Eden should have been filmed that way to accurately convey the feeling of the novel.

Narratives about the sham of the American Dream are hackneyed, yes, but that clichéd aspect didn't put me off. As grandiose as the film is (and as much as this makes it abandon certain plots or use characters as plot devices), it often shines in the details — the trip to Italy to look for the Carrara marble, for example, was the highlight of the film for me: there was something dark and inhospitable about the sequence in which the characters wander among those mountains, especially the mention of the dead-end marble caves where the people abandoned prisoners; it gave me the creeps. I just didn't like the final scene that takes place in the 1980s, I think it spoilt the conclusion of the story a little.

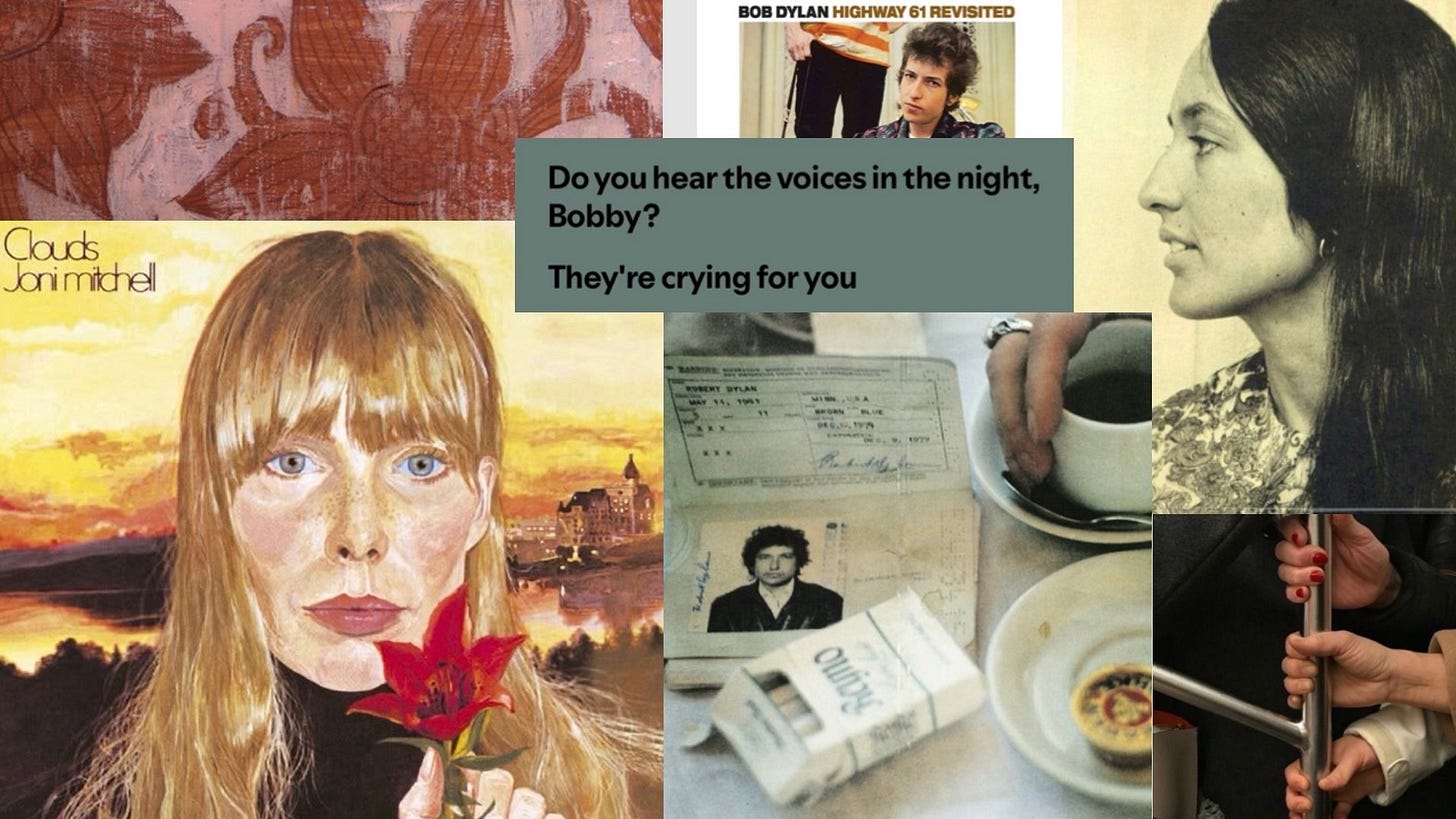

A Complete Unknown - James Mangold (2024)

I confess that I was ready to hate this film because (1) I can't stand biopics any more and (2) I didn't like the choice of actors for Bob Dylan and Joan Baez (not least because I'm completely obsessed with Joan). However, I was positively surprised and ended up having a lot of fun during the film. It's hard not to sing along at the cinema (so much so that I did, I'm sorry to anyone who sits next to me, I have no restraint) and Timothee was actually great in the role — even my father, who is a musician and a big Bob Dylan fan, said that Timothee's musical versions were better than the originals (I thought that was an exaggeration...).

MUSIC & PODCASTS

Modernist Novel - Why Theory Podcast

This is one of my favourite podcasts (perhaps you've noticed) and this episode is very interesting. One highlight was the difference between the ending of a modernist novel and that of a traditional 19th century novel: the former has ‘an ending that points to itself,’ which doesn't necessarily offer a conclusion; the latter has endings that offer a satisfactory conclusion, both narratively and morally, bringing an absolute resolution without giving a sense of continuity. Of course, this is not the rule, but it is a pattern that is in keeping with the modernist disillusionment addressed in The Waste Land, for example. It's well worth a listen if you're interested in the history of the novel.

It Ain’t Me Babe playlist

Ever since I saw the Bob Dylan film, I haven't stopped listening to Bob Dylan — it's a sickness; my sister can't stand to hear me humming ‘Like a Rolling Stone’ around the house anymore. I've had an obsession with Joan Baez and her relationship with Dylan for years, and this playlist is old, but I started listening to it again after the film.

Clouds - Joni Mitchell (1969)

I always have one of Joni Mitchell's albums on rotation, and my pick of the moment is Clouds. I hadn't listened to it from start to finish until recently. The song ‘I Think I Understand’ is my favourite and one of the songs I've listened to the most this month. It has beautiful lyrics that really moved me: ‘Back along the pathway of a troubled mind / When forests rise to block the light / That keeps a traveller sane / I'll challenge them with flashes from a brighter time / Oh, I think I understand / Fear is like a wilderland’