Indiscriminate and Erratic

An essay on writing diaries

“The Philosopher is akin to the Poet in this, that both are concerned with the mirandum, the ‘wondrous’, the astonishing, or whatever calls for astonishment or wonder.” Thomas Aquinas in his Commentary on Aristotle’s Metaphysics; I, 3

What we deem worth remembering is almost always The Great Event, the strange, the extra-ordinary or even the supernatural, while the prosaic phenomena that make up the majority of our lives clump together in a blur unworthy of recording. The world seems to be guided by a metric of scandal and, under this influence, I have developed a fear of not being able to retain the details of everyday life as much as I would like to.

It's difficult to deal with the passage of time. I've always been painfully aware of the inevitable deterioration of the world as well as myself – it's what prevents me from living fully in the present and, paradoxically, makes me want to capture it at all costs, as if I could override its ephemeral essence. Feeling disquieted, I got into the habit of writing diaries: it's a way of embodying memories so that in twenty, thirty years' time, I can look back at my past through these pages and feel that it has never completely dissolved. I do this – I lie to myself – even though I know the truth: Time, as nature's truly democratic agent, will trample over everything whether or not I try to escape it. In fact, there really is no escape, but the prospect of inevitable destruction can't stop me from trying to preserve certain things; that can't be the defining purpose of creation – otherwise neither I nor anyone else would create anything. It's the innocuous aspect of this endeavour that I find charming.

This habit of the diariste – a term used to categorise authors such as Anaïs Nin and the Goncourt brothers – is no mere historical-factual record. In the preface to Studies in The History of the Renaissance, one of my favourite books, Walter Pater advocates a subjective approach to art and literary criticism, presenting a method based on individual impressions: “What is this song or picture, this engaging personality presented in life or in a book, to me? Does it give me pleasure? and if so, what sort or degree of pleasure? How is my nature modified by it?”.

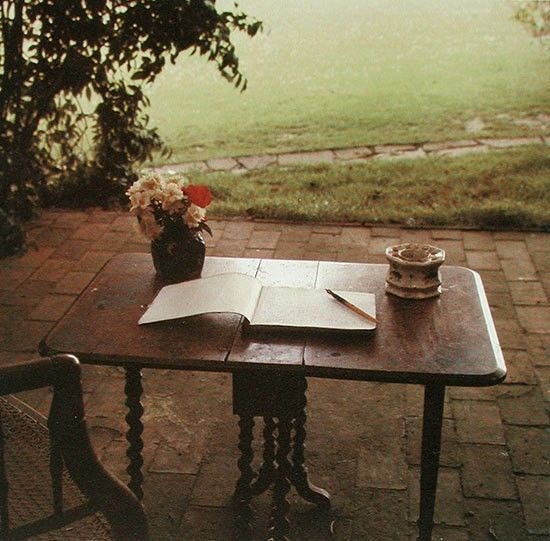

It is in this impressionistic way that I record ideas, observations, events and reflections in my diary, from a decidedly subjective perspective, with no commitment to justice or impartiality: the aim is to capture my impression of that moment as literally and freely as possible. Literal because I don't worry about style and consistency, because we don't think according to aesthetic rules and, as there is no reader, I am free to write in a way that is sincere and incoherent to the point of embarrassment.

As well as being impressionistic, this type of writing is introspective. The gaze travels extensively outwards, but the destination is always inwards. It's what Joan Didion called “the implacable ‘I’” in diary writing in On Keeping a Notebook, which grants a liberating non-commitment to the facts while preserving a very personal vision of the diarist and enabling the construction of an individual/particular anthropology:

“We are not talking here about the kind of notebook that is patently for public consumption, a structural conceit for binding together a series of graceful pensees; we are talking about something private, about bits of the mind's string too short to use, an indiscriminate and erratic assemblage with meaning only for its maker.”

Not only am I genuinely curious about an infinite number of things, but I'm also a great enthusiast of my own observations. I carefully collect them, motivated partly by hubris and partly by pure artistic intentions, harbouring the certainty that one out of a hundred will be genius. That's why “indiscriminate and erratic” is how I would describe most of the interests noted in my diary.

A year ago, under the influence of Annie Dillard's Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, I developed a passion for observing nature. In the diary from that period, you can find minute observations of the trees, birds and flowers I saw walking around, along with romantic impressions that were actually pitiful imitations of Coleridge and Rousseau. It’s interesting to note how my writing is always heavily influenced by what I’m reading. Another time, I thought I was receiving divine messages through a series of literary coincidences found in East of Eden and Paradise Lost that for me formed patterns of meaning – another demonstration of hubris, duly recorded in the diary, but at least those neurotic pages became a nice essay. How is this relevant if the aim is to capture my memories? Well, it depends on the concept of memory. For me, it's much more significant to record who I was at that moment than the events that happened to me, as if I were a passive figure in this auto-narrative, which isn’t the case.

Becoming aware of this writing process made me realise that everything is important to me. Nothing is so small or simple that it isn't worth remembering, recalling, rethinking, narrating and keeping. Recording the daily process by which I understand myself in the midst of contradictions is the method I've found to preserve my existence in the purest form – sometimes I try to capture the “instant-now” formulated by Clarice Lispector in Água Viva, with the aim of crystallising the people I am/was, through observations of the world transformed into impressions. But, again, I know it's no use. It reminds me of T.S. Eliot’s enigmatic verses from Four Quartets: “If all time is eternally present | All time is unredeemable”.

I’m also reminded of Thomas de Quincey, when he said: “If in this world there is one misery having no relief, it is the pressure on the heart from the Incommunicable” – the attempt to exhaust all experience and capture it instantly and precisely is a pleasant idea, but one doomed to failure. The imperfect effort is always what remains, and the negative space – the palpable absence – in which the ineffable consists is the misery of which Quincey speaks; a misery that warns me to immerse myself in sensations first and worry about capturing them later, since such a capture is impossible. Yes, I know there's no point in trying to prolong the present – it has already become a memory the moment I write about it. However, every day something happens that persuades me to try anyway.

There is no single, objective version of an event because every memory is tinged with the subjectivity of its observer, but that is precisely what I want to capture: what defines me is not the events themselves but how I make sense of them; writing down my life as it happens, as Clarice tries to do in her strange novel, is an activity that has completely changed my way of thinking and seeing the world.

David Foster Wallace, in his essay This Is Water, spoke about the “unimaginable difficulty of remaining conscious in the adult world”, that is, the rapid repetitions of modern routine prevent contemplation and true observation, through which we can become aware of our surroundings and, consequently, of ourselves. To do this, you have to make a deliberate effort to be an attentive observer through a process of denaturalisation (the one devised by Viktor Shklovsky) that extracts the abstractness of sensations from everything that is, at first, trivial.

For the keen observer, anything can cause enchantment and awe. That's why I get distressed thinking about the possibility of letting something marvellous fall by the wayside. But that's nothing to be sad about, because it means that there will always be mystery in the world, the unspeakable and invisible, which may or may not be discovered – possibilities will always remain.

I still have my diary from when I was eight years old. In it, I wrote that it was natural for a human being to have enemies and that people shouldn’t blame God for things since he doesn’t interfere in our lives. I didn’t remember being such a cynical child and it was a hilarious discovery. A few years later, I wrote down my frustrations about people in school thinking I was mean when I was only being honest (an extremely common misconception in youth). I recognise these rough sentiments because I still feel them, only in a more self-aware, civilised way. I enjoy being able to trace the development of my personhood – it’s educational. There is comfort in thinking that this infant version of me – and many others – will be preserved in a notebook after I’m gone, surviving my other versions, maintaining precious parts of my many selves for as long as the paper lasts.

Adorei o texto, Julia :) Eu também sou fascinada pela escrita diarística… Há uma passagem nos diários entre 1947-1963 da Susan Sontag (publicados sob o título “Reborn”) onde ela escreve:

“Superficial to understand the journal as just a receptacle for one’s private, secret thoughts — like a confidante who is deaf, dumb and illiterate. In the journal I do not just express myself more openly than I could do to any person; I create myself.

The journal is a vehicle for my sense of selfhood. It represents me as emotionally and spiritually independent. Therefore (alas) it does not simply record my actual, daily life but rather — in many cases — offers and alternative to it.”

"As well as being impressionistic, this type of writing is introspective. The gaze travels extensively outwards, but the destination is always inwards." Beautifully put.